Studio Visit

From His Brooklyn Space, British-Jamaican Artist and Filmmaker Joseph Douglas Elmhirst Channels Memory and Reflection

Elmhirst's short film 'Burnt Milk' debuted at the British Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale last year.

Elmhirst's short film 'Burnt Milk' debuted at the British Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale last year.

Katie White

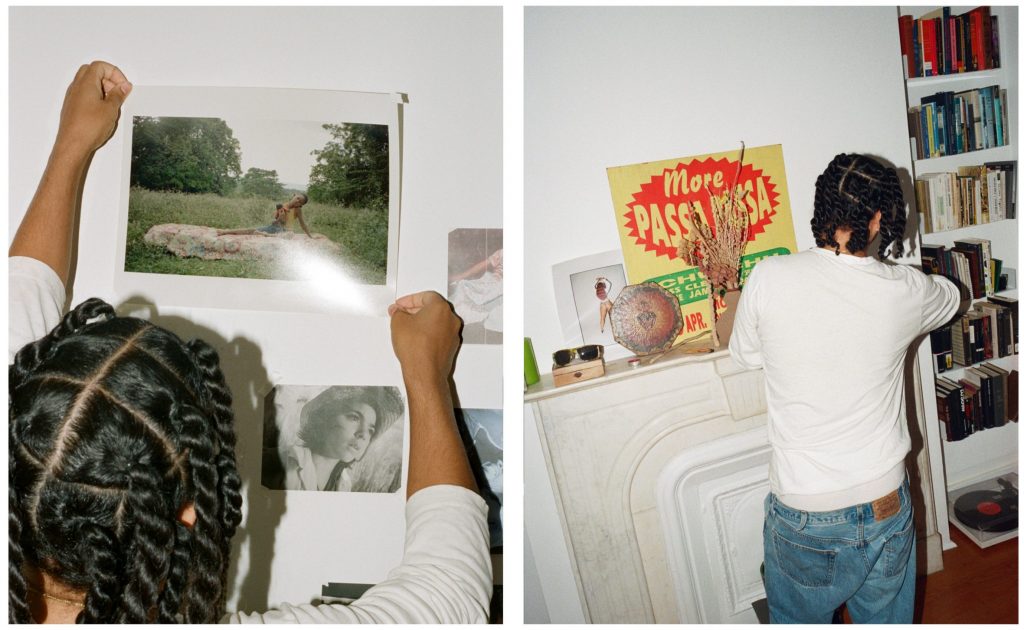

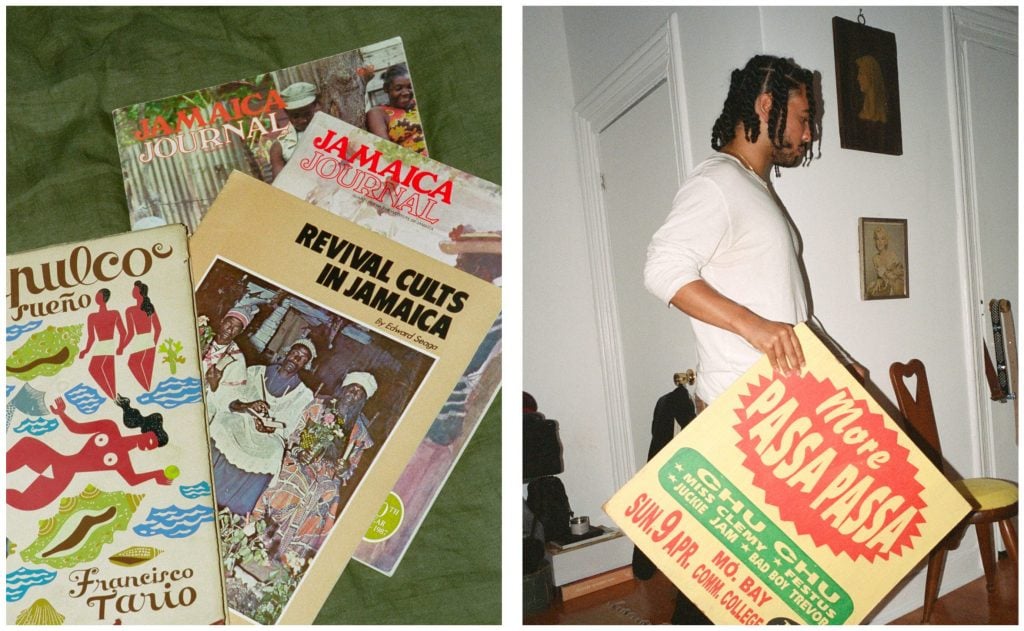

Joseph Douglas Elmhirst just turned 25, but the British-Jamaican filmmaker is already making a name for himself as an inspiring new creative voice working at the intersection of art and film. In 2020, at 21 years old, Elmhirst debuted his first film, Mada, a poetic short film that follows three generations of a rural Jamaican family across three days. In 2023, Elmhirst released his follow-up short film, Burnt Milk, a Proustian dive into sensorial reverie. Set in the London of the 1980s, the film centers on Una, a Jamaican expat, who experiences near hallucinatory visions of her homeland while boiling a can of milk in her suburban home. The film is inspired by an eponymous book written by Elmhirst’s mother and was commissioned by the British Pavilion at the 2023 Venice Architecture Biennale, as part of its presentation on ritual (the commission marks the first time film has been presented by the British Pavilion at the Architecture Biennale). The film was also awarded Best Short Film at the Black Harvest Film Festival last year.

We recently caught up with the artist and filmmaker at his New York home to discuss his inspirations, including phone calls with his mother, Marilyn Monroe ephemera, and a daily practice of meditation and prayer.

Courtesy of Joseph Douglas Elmhirst.

Tell us about your studio.

I live in New York. I work out of my home at a desk. I prefer to work alone until a certain point where I’m ready to welcome other voices in.

What are you working on right now?

A few things. We are in the middle of a festival run for a short film I directed called Burnt Milk which was inspired by my mother Miss Ronnie’s forthcoming first novel, and produced by my sister, Ruby Elmhirst. There are some special screenings coming in the spring too. I’ve also been putting together for the last year a collection of contemporary Caribbean art for a book I’m curating. It’s exciting to put artists and their work in conversation with each other, and see what beyond heritage is shared. There’s so much that hasn’t yet been articulated. And then more film projects. The first of which I’m planning to shoot in the next few months. It’s the first time I’ve also wanted to present a visual project through other tangible mediums in addition to video. I want to keep growing in terms of strengthening my own sense of language.

What kind of atmosphere do you prefer when you work? Is there anything you like to listen to/watch/read/look at etc. while in the studio for inspiration or as ambient culture?

It has to be really calm and quiet. I used to write in the library. The film Soy Cuba had a really strong impact on me, so I come back to that. Pedro Costa and Francesca Woodman’s work too. I play a lot of Oneohtrix Point Never & Aphex Twin. I listen to Nicki Minaj a lot. Mahalia Jackson. I like Rajahwild. I’ll also just play the sound of tree frogs off YouTube. I’ve been writing and editing to that sound for rhythm. That sound which is what you hear in rural Jamaica at night has really been the score to all my visual projects. There’s something so powerful about that sound. I know it’s what my ancestors also heard. It transcends time. I’ve been lucky enough to work with Kevin Gilligan, who has changed the way I’ve understood sound. Now I think of sound as connective.

How do you know when an artwork you are working on is clicking? What do you do when the artwork you are working on feels like a dud?

For me, when I work from the inside out, rather than the outside in, it’s better. I’m guided by my instincts completely. I didn’t go to film school. I think working out the distinction between a cool idea versus something you need to give birth to, is really important. I watched the Kanye West documentary, maybe a year or so ago, and I was really inspired by his productivity. He, even at my age, just pushed through and built a body of work. If something isn’t clicking I just go for a walk. I like walking up and down Fulton Street in Brooklyn. It reminds me a lot of Shepherds Bush in London, where I lived.

Courtesy of Joseph Douglas Elmhirst. Photograph by Bryce Thomas.

What images or objects do you look at while you work?

I tried having images on the wall but I found it overwhelming. I took them all down.

What’s the last museum exhibition or gallery show you saw that really affected you and why?

I would have liked to have gone to Isaac Julien’s show in London. I just met Dawoud Bey in Chicago, at the Black Harvest Film Festival, and I’ve been looking at his work online since. His subjects, they look right at you, it’s so intimate. I’m impressed by him as an artist, but also the impression I got of him as a person. I feel the same way about Timothy Yanick Hunter and his work.

Where do you get your food from, or what do you eat when you get hungry in the studio?

If I’m writing, I don’t like to eat. Unless I’m editing I fast until the evening. I just drink coffee. If I’m in the editing process then it’s whatever is open. I’ve been up for sometimes 20 hours if there are voices involved who are in different time zones.

Is there anything in your studio that a visitor might find surprising?

A lot of Marilyn Monroe ephemera.

What is the fanciest item in your studio? The most humble?

I have a red mirror that belonged to an artist named William Chaiken. He painted until he was 100. It’s interesting to own someone’s mirror. I don’t know if I own anything I consider humble. That’s for someone else to say.

Courtesy of Joseph Douglas Elmhirst. Photograph by Bryce Thomas.

How does your studio environment influence the way you work?

I think my space reflects my work. Most of the things here are retrospective. I want to cultivate an environment that welcomes things in. The things I’ve been conjuring feel like they were placed in me already. Or that’s the way I want to feel. It’s a hard thing to explain, but I feel like my job is to connect the dots, like I’m hitting a nerve. I don’t think I have accomplished that yet.

Connect the dots?

Yes. I think space and time and objects, like people, hold a past or memory too. And it all intersects. All this is handed down like a constant echo. I’d like to tell stories that articulate that, and center people who are trying to find power within a preordained structure that’s bigger than them. Who are trying to escape those echoes. I feel connected to those stories. Whether it’s familial or colonial, I think against the past, a lot of us have a lot less power than we realize in daily life. I don’t think there is a place I know in the world that embodies these things more than Jamaica. The past is always echoing there. You can feel it. Which is probably why all my visual projects so far have been connected to it. It’s also why Dub music, the echoes and reverbs, were a big influence on the score for Burnt Milk.

Are there artist’s that have influenced you?

David Lynch. He’s a huge influence. I admire Khalik Allah. He’s pioneered his own visual language. I feel the same way about Akeem Smith. Jacqueline Rose’s work also really influenced my process. The way she uses psychoanalysis to contextualize history helped me understand my own. I also really like this artist James Jordan Johnson, who I’ve been speaking to.

Prized possessions in your space?

Family photo albums. Then probably negatives, and hard drives, and a painting Alex Parrasch gave me.

What’s the last thing you do before you end a day of work?

I call my mother. She lives in Jamaica.

What do you like to do right after that?

I’ve been researching spiritual transference for my next film project. I just finished reading Britney Spears’s memoir. Now I’m reading Thomas Sankara Speaks.