Law & Politics

Who Owns Graffiti? A Judge Allows a Street Artist’s Lawsuit Against General Motors to Move Forward

The decision could set a precedent for how we depict buildings that contain street art.

The decision could set a precedent for how we depict buildings that contain street art.

Sarah Cascone

The Swiss street artist Adrian Falkner, also known as Smash 137, will have his day in court with General Motors. A federal judge in Los Angeles has rejected GM’s attempt to dismiss the artist’s claim that the automaker infringed on his copyright when it included a photo of one of his murals in its 2016 Cadillac ad campaign.

Falkner’s attorney, Jeff Gluck, told the Detroit Free Press that the move was “a massive victory for artists’ rights.” A ruling in the artist’s favor could set a precedent for future lawsuits in connection with the unauthorized reproduction of graffiti art.

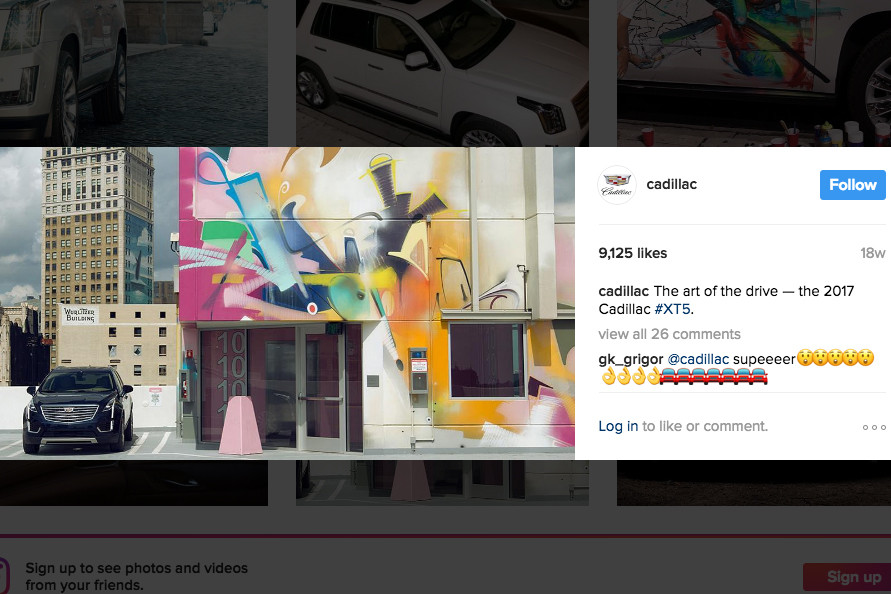

A photo featuring Falkner’s 2014 mural on a Detroit building facade was promoted on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter in GM’s “The Art of the Drive” social media campaign. Even though it was not part of GM’s larger advertising strategy for the Cadillac XT5, Falkner argued in his complaint that the image was likely seen by millions of people and “damages his reputation, especially because he has carefully and selectively approached any association with corporate culture and mass-market consumerism.”

GM used this photo with a mural by Adrian Falkner, also known as SMASH 137, in a 2016 social media campaign. Screenshot courtesy of Adrian Falkner.

GM had argued that its use of Falkner’s mural was legal because copyright law allows photographic depictions of architectural works. “This right to photograph an architectural work extends to those portions of the work containing pictorial, graphic, or sculptural elements,” the company argued in a July legal filing. “Because [Falkner’s] mural is painted onto an architectural work, it falls squarely within the ‘pictorial representation’ exemption, and his copyright infringement claim should be dismissed.”

The judge looked at a similar case in which artist Andrew Leicester sued Warner Brothers for filming the courtyard of a building that housed his sculptural work, which appeared in Batman Forever. That case was decided in favor of Warner Brothers because Leicester’s work was designed in tandem with the rest of the structure, and were thus considered part of the architectural design.

GM used this photo featuring a mural by Adrian Falkner, also known as SMASH 137, in a 2016 ad campaign on social media. Photo courtesy of GM.

Falkner, on the other hand, created his mural after the parking garage was completed. In his ruling, Judge Steven Wilson noted that the artist “was afforded complete creative freedom with respect to the mural, and… was not instructed that the mural should play a functional role with respect to the parking garage or that the design of the mural should match design elements of the garage.” Because Falkner’s mural is not being considered a part of the architecture his copyright infringement claim can be heard.

“Graffiti artists often aggregate their work on public and private property,” says Sam P. Israel, an attorney who specializes in intellectual property law but is not involved in this case. “If GM loses the trial and the plaintiff’s graffiti is deemed to have a copyrightable identity separate from the architectural configuration, it boggles the mind to think of the licensing costs for depicting architecture that’s been enhanced by multiple artists.”

The judge did dismiss two of Falkner’s claims, however, including one for punitive damages. The artist could still win up to $150,000 at trial if GM is found to have willfully infringed his copyright, plus any actual damages.