People

Muralist and Public Art Advocate Judy Baca on Her New Show at MOCA Los Angeles, and Why So Much Community Art Is ‘Denigrated’

The 76-year-old public artist is having a moment at major U.S. institutions.

The 76-year-old public artist is having a moment at major U.S. institutions.

Catherine Wagley

Judy Baca’s World Wall mural is like so many of the artist’s projects: bold, expansive, collaborative––and incomplete. The nine 30-foot wide paintings that currently comprise the project have been exhibited in Mexico City, Moscow, and Dallas. Now, they occupy the sprawling southernmost gallery of the Geffen Contemporary at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

Each mural grapples with peace and a future free of fear. Baca painted four herself with collaborators, and found artists from Mexico, Finland, Russia, Canada, Israel, and Palestine for the others. Initially, she imagined 14 murals, and now, 35 years in, she still plans to complete the rest. (After all, world peace has not yet been achieved.)

For decades, Baca, who is 76, has been a relentless advocate for public art in Los Angeles. In the 1970s, she initiated the Citywide Mural Project under the auspices of the L.A. Parks and Recreation Department. Then she and two other artists co-founded the Social and Public Art Resource Center. In 1976, she began painting the half-mile mural The Great Wall of Los Angeles, with the help of countless collaborators (she is currently expanding this mural). The Great Wall spurred World Wall after two young girls helping with the mural asked her what peace looked like.

MOCA’s exhibition “Judy F. Baca: World Wall” is one of multiple recent institutional shows for the artist (a New York Times headline called this “A Baca Moment”). In May, the Getty Center opened an exhibition devoted to Hitting the Wall, Baca’s 1984 freeway mural of an Olympic runner. But her work still often feels like a battle. After a Metro employee whitewashed Hitting the Wall in 2019, Baca sued the L.A. transit authority and CalTrans, and put funds she won toward its restoration.

When I met Baca at MOCA, we talked about the difficulties of making art in public. But first, we looked closely at the paintings, marveling at how good they looked, framed by the rows of steel-encased pillars that run down the center of the warehouse-like space.

Installation view of “Judith F. Baca: World Wall,” September 10, 2022–February 19, 2023 at the Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA). Photo by Jeff McLane.

The Geffen is a perfect space for this.

Oh my God. It’s as if it was designed for it. At first when Anna [Katz, the show’s curator] proposed it, I thought, “Wow, this isn’t going to really work because of the pillars.” But what is so interesting is that the pillars just invite you to come in and see the piece, and then it’s perfectly framed, right? And you know, this work was so ahead of its time.

But it’s also of its time, with its specific references, like to Tiananmen Square and the 1994 Chiapas Rebellion.

This started when there was a march planned during the arms race. There were going to be 5,000 people in a tent city marching across the country. And I was asked by David Mixner, a political organizer, “Could you create an arena for dialogue?”

So this was always about making space for other people?

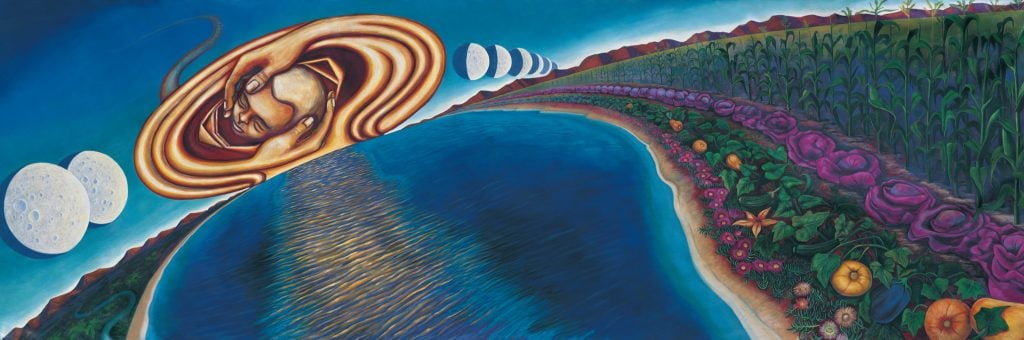

It was about creating a space in which all the pieces were speaking to each other. And then the people would come inside the space and speak. So that’s how that piece came about [she gestures toward her painting Nonviolent Resistance (1987–91)]. It came about from looking at the fact that agribusiness had destroyed the earth with harvesting the same foods over and over again and depleting the soils.

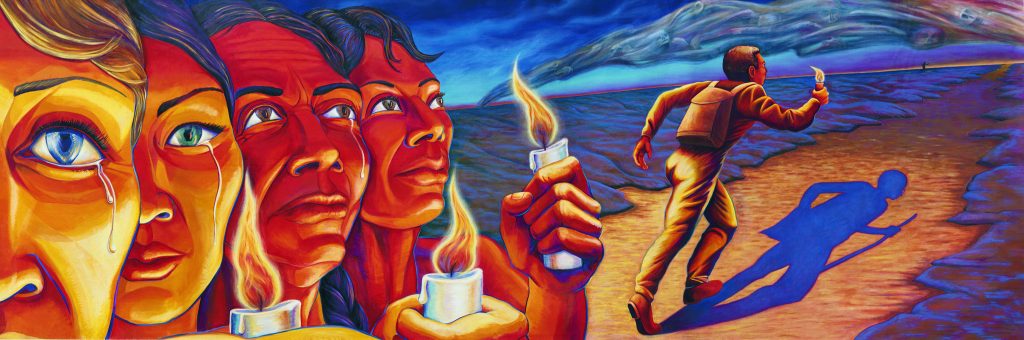

[Baca turns toward her painting Balance (1987-1990).] And this one is like a primer on how you get to balance. The first act essentially is transformation of self. In other words, you first do a self-examination, then you step into historical precedence, and you always know that there are people waiting on the horizon that are part of a community of consciousness. You seek them out and then you start to work together. But always the winds of war are eminent. It’s never something you sit back on.

The urgency has always been there.

Part of what I’m trying to convey is that there is urgency and that you need to be part of the process, or we’re going to lose our democracy. My generation did a big job, but now the next generation has to step forward, and the next. I think [Balance] is my favorite painting of all my paintings.

Balance (1987-90) by Judith F. Baca, one of nine panels from the World Wall: A Vision of the Future Without Fear (1987-ongoing). Image courtesy of the SPARC Archives SPARCinLA.org. Judith F. Baca ©1990.

What makes it your favorite?

It puts you at a tilt, right? It makes you understand that you’re trying to balance inside of yourself. And the sun and the moon, the male and the female, the earth and living things, and the cycles of the moon, it’s all in this piece. It’s implied in the way that it has such depth.

I was wondering how you found the artists to make the other murals.

It was actually different in each of the places. In Russia, it was the beginning of perestroika. I went over with a peace committee, and it was the first time people were coming in to do collaborations with Soviets. I proposed this idea of wanting to have a Russian addition to this traveling mural, and then the USSR Artist Union [tried to get involved]. I didn’t really want to have this become an official communication between countries.

Official interventions would come with agendas.

I wanted it to be artists talking to artists. No U.S. Information Service monies. No support from larger authority figures. I met a group of women artists. I went to their studio, and there was a young woman there who heard me, through translators, talk about what I was looking to do. She said, “I know the perfect person for you.”

His name was Alexi Begov—he just died recently. That was a feat to get all the way to the outskirts of Moscow where his studio was. We hawked cartons of Marlboros on the street to get a ride. It was January and there was very little sun. We went up to his studio and then he brought his paintings out one after the other. They had the look of Siqueiros, and I was totally impressed. Then it was over a series of meetings that I had to convince him that I would indeed let him do whatever he wanted. He didn’t think I could take the painting out [of the Soviet Union]. So it was back and forth through translators, hours and hours of discussions. Lots of champagne. There was a shortage of food. There was a shortage of everything. But we could get champagne all the time. And finally, I said, “You just do the drawings and send them to me and tell me what you’re thinking about. It’s just a vision of the future without fear.” But he couldn’t come up with a vision of the future without fear.

Judith F. Baca ©1990, “World Wall: A Vision of the Future Without Fear” at Gorky Park, Moscow, July 14–22, 1990. Image courtesy of the SPARC Archives SPARCinLA.org.

It needed to have some aspect of fear to feel real to him?

There was no hope. This is waiting for the end of the 20th century. And you know, it turns out he was right. Putin is a great example of what has happened. I mean, it was actually more hopeful then than it is now.

That hadn’t occurred to me, that asking artists to imagine a vision of peace might have been really difficult for them.

Yes. There were three different artists [who made the mural Inheritance and Compromise, 1998], and at the time they started, I think all of them had partners. But in the process, they ended up [alone].

Suliman Mansour—he painted his father and his family with their olive grove—is Palestinian. And the three figures were [painted] by Ahmed Bweerat, who is an Israeli Arab. Then the last angel figure is by a Jewish artist from Israel, Adi Yekutieli. They suggested that everybody work in their home communities and then bring back their drawings on the vision of the future, and they would put them together in Jerusalem. I was going to join them there and help them get the painting done, but then [the border closed], which meant there was no crossing between the two different parts of the city. So Suliman couldn’t go.

I wrote to them and I said, “Could you come to California? Because I have a military base I’m working on converting, and I have military tank buildings.” They said yes. And then I wrote back: “Could you live in one barracks together?” They said, “We think so.”

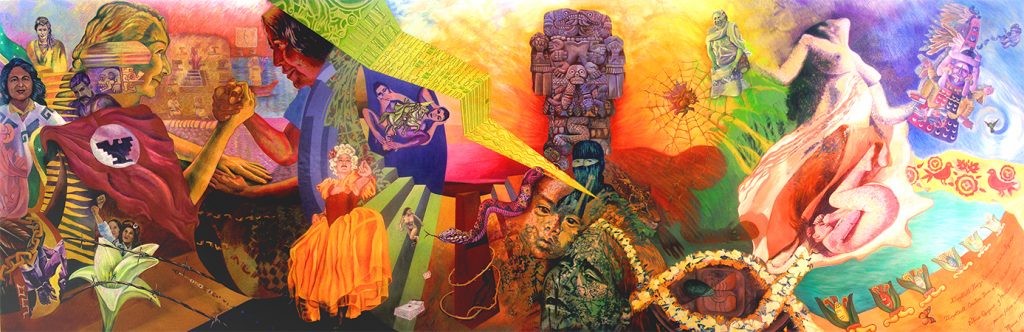

Tlazolteotl: Fuerza Creadora de le No Tejido (The Creative Force of the Unwoven) (1999), panel by Mexican artists Martha Ramirez Oropeza and Patricia Quijano Ferrer, one of nine panels from the “World Wall: A Vision of the Future Without Fear” (1987- ongoing). Image courtesy of the SPARC Archives SPARCinLA.org. Judith F. Baca ©1990.

For so long, it seems like you made your own institutions, like the Social and Public Art Resource Center—or these barracks, which became part of CalState Monterrey Bay, where you were among the founding faculty. Preservation was even something you did for yourself and other muralists.

I had to do it all. There wasn’t any system that would support what I was doing. And in fact, nobody thought it was art.

What did they think it was? Just community outreach?

Well, community art was a kind of denigrated term. It was kiddie art. It was not serious work. I think people even today are surprised that they’re this good, that they’re beautiful paintings. It’s so ideal that it’s hokey, right?

But this is dead serious art, dead serious thought, and consummate painting. But figurative painting itself was also denigrated for the most part, and there wasn’t any place for me to go as a woman and as a monument maker, and as a person who worked in scale. I had to invent it. I didn’t really want to. In fact, I just lament that I have to still keep an institution going. I’m so tired. The hardest thing I’ve had to deal with is leadership—who can lead, who knows how to lead in a way that is not the male model?

But that’s really valuable. Figuring that out then becomes a model for other people who want to figure it out in the future.

It’s very hard.

And slow.

Because people think it’s weakness, right? They mistake my compassion, my lack of an assertive nature, as weakness. Although I always kid everybody in my lab: I say “the sheriff’s back in town” when I come back in, because that means I’m holding people to deadlines. It’s no easy place to work. We’re always working with no money, and we always don’t have the support we need. Although some of that’s changing a bit.

I heard you say in your Getty talk that the institutions, communities, and local municipalities need to hold hands—that there needs to be a collaborative effort to preserve the murals that are already out there and to make this work possible.

Yeah. But if you go onto the Harbor Freeway today, you’ll see Hitting the Wall, which commemorates women running the marathon for the first time in 1984. It’s totally destroyed. And that’s misogyny by young men who keep hitting it with graffiti when there’s walls alongside of it that they could hit. Then they’re posting [on social media] that they managed to destroy it. So it’s a feat to take a 30-foot woman off the wall. And the city has still not stepped forward to create the support for artists to maintain these works.

You’re using the lawsuit money to restore it yourself, right?

I’m going to run out shortly. There was $300,000 or something that I got from [the lawsuit], and I’m just now doing the second restoration and it’s really expensive.

Triumph of the Heart (1987-90), by Judith F. Baca, one of nine panels from the “World Wall: A Vision of the Future Without Fear” (1987-ongoing). Image courtesy of the SPARC Archives SPARCinLA.org. Judith F. Baca ©1990.

With the increased institutional recognition of these artworks as artworks, are you getting more support for preservation? I mean, the Getty has resources.

They did an exhibition for me this year—which was an amazing, remarkable experience—about that mural. But they have yet to step up and say, “we’ll maintain it.”

Murals have such a long history. It’s a form that’s been championed by so many amazing artists. And yet why don’t more institutions treat conserving these works as their role?

It’s associated so effectively with people of color, which has made it less than desirable. In other words, no one can own a mural. Therefore, it’s not valuable. The value [of art] is created by who owns it, and whether you can restrict viewing access to it.

And the other part of it is that the content of many of these pieces is speaking about things we don’t want to talk about. We don’t want to remember that it was only in 1984 that women were allowed to run in the Olympics. And very often, with a lot of the works I did early on, I didn’t even sign them—so where does my hand begin and someone else’s end?

The installation here at MOCA doesn’t privilege anyone over anyone else.

I just keep operating in the way people should operate. You model the behavior you want from others, right? But this is a big we; we did this [gesturing toward the World Wall murals].

But now we’re in this terrible period that we’re in right now, and I’m revisiting the ’60s at the Great Wall [as part of its ongoing expansion]. Can you imagine?

I’ve been reading a lot about activism and cultural movements in the 1960s. It can be depressing to think about the world we could have had. I’ve also been thinking about the Brockman Gallery [founded in 1967 in L.A. to promote artists of color], which supported mural projects too.

We worked with Brockman a lot. There weren’t that many of us, but we held hands and we just tried to keep hope alive.

I always think about how the Brockman Gallery’s archive didn’t go to a place like the Getty, because Dale Davis, who co-founded the gallery, was looking for somewhere more accessible. It went to the public library.

We wouldn’t give our archive to the Getty. Why would you give the currency of people of color to the white power of the castle on the hill?

I’ve got to start figuring out where everything’s going too. Where are these going to go [indicating the surrounding murals]? Where should they reside and how should they continue? I can’t keep managing this thing, because—what?—I’m going to manage it when I’m 80? I need to finish these giant designs for the next segments of the Great Wall. And then I think I’m done with this kind of scale. I think the next stuff I want to do is about global warming today. It’s really the focus now. We need to get people’s consciousnesses on what’s happening.