Art World

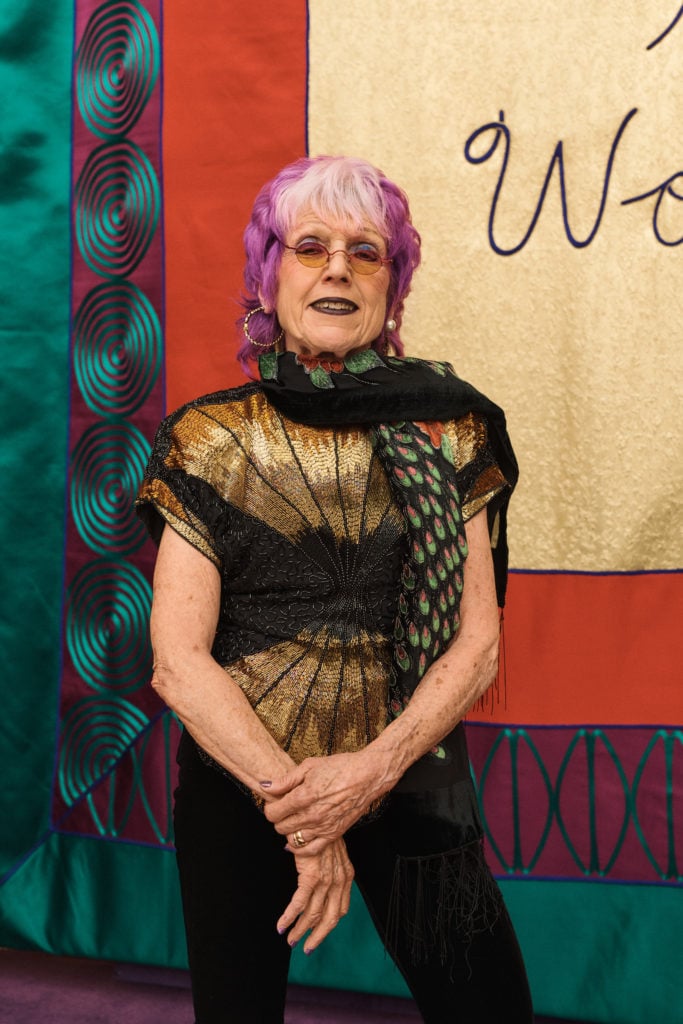

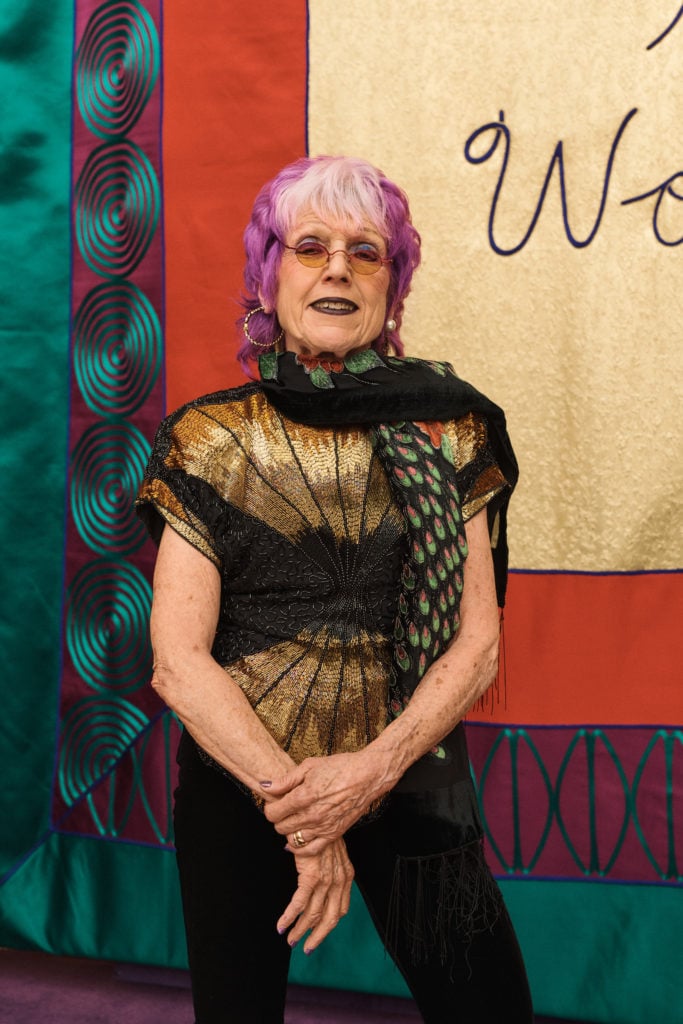

‘This Has Been the Greatest Creative Opportunity of My Life’: Judy Chicago on How Working With Dior Changed Her Mind About the Fashion World

The artist conceived the staging for Dior’s couture collection presentation on Monday.

The artist conceived the staging for Dior’s couture collection presentation on Monday.

Noor Brara

In the gardens of the Rodin Museum in Paris on Monday afternoon, fashion-week attendees funneled through the entryway of a mammoth white tent structure for the presentation of Dior’s spring/summer 2020 couture collection. The towering 45-foot-tall installation, which greeted guests upon arrival, heralded what is arguably one of the most ambitious art-and-fashion partnerships in recent years, bringing together Dior creative director Maria Grazia Chiuri and the great feminist artist Judy Chicago.

Last spring, after Chiuri named Chicago as one of her 10 biggest influences, the artist started looking into Chiuri’s collaborations with feminist writers and artists, from Nigerian novelist Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, whose manifesto, We Should All Be Feminists, was emblazoned across a t-shirt in the designer’s inaugural show for Dior in the spring of 2017, to the British-born Surrealist artist Penny Slinger, who conceived a a dollhouse-inspired set for the autumn/winter 2019 collection, presented last July.

“I have to tell you, I didn’t know who Maria Grazia Chiuri was,” Chicago told Artnet News a few days before the show. “But I quickly did some research and discovered that she was the first female creative director at Dior. I read that she’d been doing collaborations with other feminist artists, and that she’d caused a stir with her first collection. I thought that was interesting.”

Chicago’s womb-like entryway into the Dior show. Photo courtesy Christian Dior.

Chicago posed for a photograph that ran alongside Chiuri’s influences interview in the German magazine Frankfurter Allgemeine Quarterly, and thought that was the end of it. But before long, she received an invitation—addressed not only to her, but also to her husband, the photographer Donald Woodman—to attend Dior’s July couture presentation in Paris.

“I assumed she had invited all 10 of the women she had named in the article,” Chicago said. “But I found out that she’d only invited us because she wanted to talk to me about doing a collaboration.”

“We were incredibly blown away,” the artist recalled of the show. “I’d never been to a couture show before, and I saw how they had incorporated Penny Slinger’s photographs. By this time, I’d read a lot of the feminist critiques of fashion and as much as I’d thought of fashion as sort of a threat to women—all these male designers asking women to wear these ridiculous high heels and telling us what our bodies should look like—I started to ask myself, ‘Can art have any real place here? Is there a way to really use fashion to empower women?’”

When Chicago and Chiuri finally met after the show, Chiuri proposed that the artist work with her to produce the runway show for her next collection, basing the set design loosely on Chicago’s The Dinner Party (1974–79). That prodigious artwork, which is permanently installed at the Brooklyn Museum, consists of a large-scale triangular dinner table with intricate place settings laid out for 39 historical feminist icons.

Chicago, however, wasn’t interested. “My whole focus these days is trying to get my body of work out from under the shadow of The Dinner Party,” she said. “And Maria Grazia’s next show was ready-to-wear, and I didn’t want anything to do with ready-to-wear. My ambitions have always been about making a contribution to art history through the most difficult vehicles, which are painting and sculpture. It’s much easier to do it in other ways—you know, that’s why a lot of feminist artists have chosen performance, or video, or photography. And I wanted to work on couture, on high art.”

A view of Chicago’s goddess structure. Photo courtesy Christian Dior.

Chicago and Chiuri agreed to reconvene at the artist’s home in the fall, so that Chicago could submit her idea for the next couture collection, which was to be presented in January at the Rodin museum, in the garden. “I think they assumed I lived in New York,” Chicago said, with a smile. “They came to my home in Belen, New Mexico which has only, you know, 18 fast-food restaurants and primarily New Mexican food.”

When the time came, Chicago presented the team with her idea: to show the collection inside the body of a giant structure built to resemble a goddess. (She had conceived an earlier version of the structure in the 1970s, but never built it.) Chicago had visited the Rodin in July while in Paris and, along with the help of her husband, built a digital model of her vision, superimposed onto photographs of the museum’s garden. Chiuri immediately fell in love with Chicago’s proposal, having long worked to celebrate the female spirit and form through her own design work.

“I called it The Female Divine,” Chicago said. “An inflatable structure with white outer fabric and inner gold fabric. The interior would feature embroidery, which I studied when I was working on The Dinner Party, and thinking about how to make the feminine sacred. I learned a lot about the ways in which needlework—often done by women—has historically been used to aggrandize the male body, and the whole patriarchal structure of the church. I wanted it to aggrandize women’s contributions and achievements instead.”

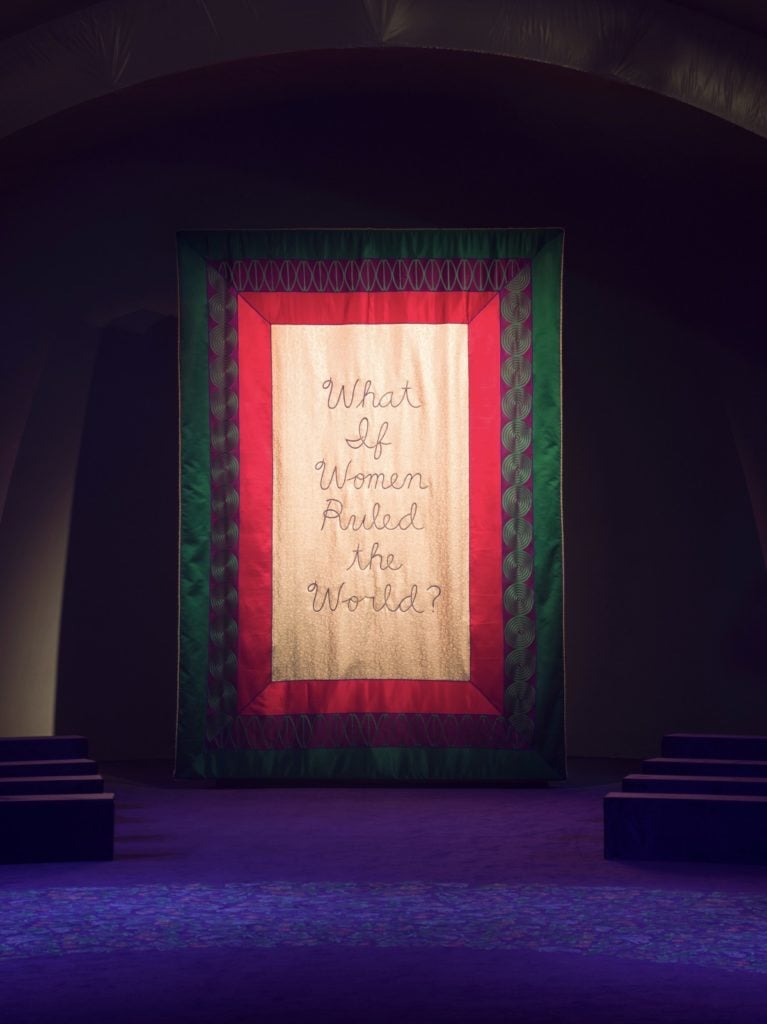

Chicago proposed creating 21 brocade, hand-embroidered banners—10 in English, 10 in French—that each featured an essential question relating to the central premise of her lifelong query: “What if women ruled the world?” These banners, each 10 feet tall and 7 feet wide, would line the ceiling and hang above the runway.

Chicago’s “What If Women Ruled the World?” banner. Photo courtesy Christian Dior.

Recently, Chicago took a trip to the Dior archives to learn more about the house’s history of embroidery and craft. The experience was transformative in many ways, and shifted her perception of the fashion world.

“There I was, coming from high art to the Dior archives and thinking, ‘My god, I have more in common with the kind of environment that respects craft and keeps that art alive than I do with the art world, where nobody knows anything about that kind of work,” Chicago said. “It was incredible.”

The final part of Chicago’s plan was to feature a millefleur catwalk comprised of real flowers in rich tones of purple, magenta, red, and green—a version of an earlier idea she wanted to borrow from Frédéric Tcheng’s 2015 documentary Dior and I, which captured former creative director Raf Simons’s now-famous decision to festoon Dior’s five-room headquarters with a million flowers for his first show. “That was my concept—a million fresh flowers on the runway!” Chicago said. “But then they said they were thinking of actually keeping the structure up for a week after the show, so people could continue to visit and view it. They proposed a 600-foot-long millefleur carpet instead.”

Over the following months, Chicago and Dior’s creative teams exchanged drawings and fabric samples, ensuring each piece of the process fell perfectly in line with Chicago’s vision. They met twice in New York, taking meetings with famed runway-designer Alexander Betak’s team, who were responsible for building the structure and installation. Once everything was in place, Chiuri told Chicago she wanted the embroidery to be done by a group of female students from the Chanakya School of Craft, a nonprofit organization in Mumbai supported by Dior that teaches women craft-based skills that have historically been practiced by men.

Inside the Dior show. Image courtesy Christian Dior.

“I was talking to Maria Grazia’s assistant the other day, and she said to me, ‘Judy, isn’t it incredible? We were in this small office in Belen, and this project has crossed the globe from Belen to New York to Paris to Mumbai,” Chicago said.

While the show itself debuted to great success—culminating, fittingly, in a beautiful dinner party for 160 people in the evening, which brought Chicago’s work full circle and featured editioned goddess plates designed by the artist, soon to be available for purchase through Dior—Chicago is perhaps most surprised by how the collaboration was able to convey a genuine message of female empowerment that had little to do with product-pushing. In her eyes, what she and Chiuri created was, truly, art.

“Without a doubt, this has been the greatest creative opportunity of my life,” Chicago said. “And what I think now about the relationship between art and fashion is that fashion can really be a vehicle for meaningful art. I think this can be a whole other model for how the worlds of art and fashion can collaborate that’s not about commercialism or taking Old Master paintings and slapping them on purses. Art has to be more than the marketplace. It has to mean something.”

“I hope that this project can make a contribution to an understanding of how art can make a real, meaningful offering within the framework of fashion,” she continued. “And I also hope it will contribute to change so that fashion becomes a vehicle of the empowerment of women rather than a symbol of the oppression of women.”