Art & Exhibitions

How Artist Katie Hector Achieves Her Spellbinding Portraits Without Using a Drop of Paint

The artist's solo exhibition "Ego Rip" is on view at Management gallery in New York.

The artist's solo exhibition "Ego Rip" is on view at Management gallery in New York.

Annikka Olsen

Viewers could be forgiven for losing track of time lingering in front of one of Katie Hector’s paintings, induced into something akin to reverie or reminiscence through their mesmeric ranges of color optically advancing and receding. Hector, an artist based outside of Los Angeles, employs a unique method of painting to create her spellbinding portraits—unique namely in that it doesn’t involve paint, in the traditional sense, at all. Instead, she uses bleach and dyes to create her compositions, a technique born out of experimentation in the studio during the pandemic.

“It was mid-pandemic, which afforded me the solitude to tweak the process,” Hector said via email. “Applying layers and introducing moments of erasure makes each painting feel alive and allows me to have a different conversation with the physical canvas as well as the image.”

Installation view of “Katie Hector: Ego Rip” (2024). Courtesy of Management, New York.

In her solo exhibition “Ego Rip” at Management in New York, on view through May 12, Hector’s refinement of this technical process reaches dazzling heights and clarity. At first the figures appear almost chrome, but with closer inspection recall alternate ways of seeing, like infrared, x-ray, or thermal imaging. Despite the visual gratification of the vibrant figuration, however, the show carries a heavy emotional weight throughout; a sense of loss, grief, and nostalgia is pervasive, and speaks to the core themes of the show.

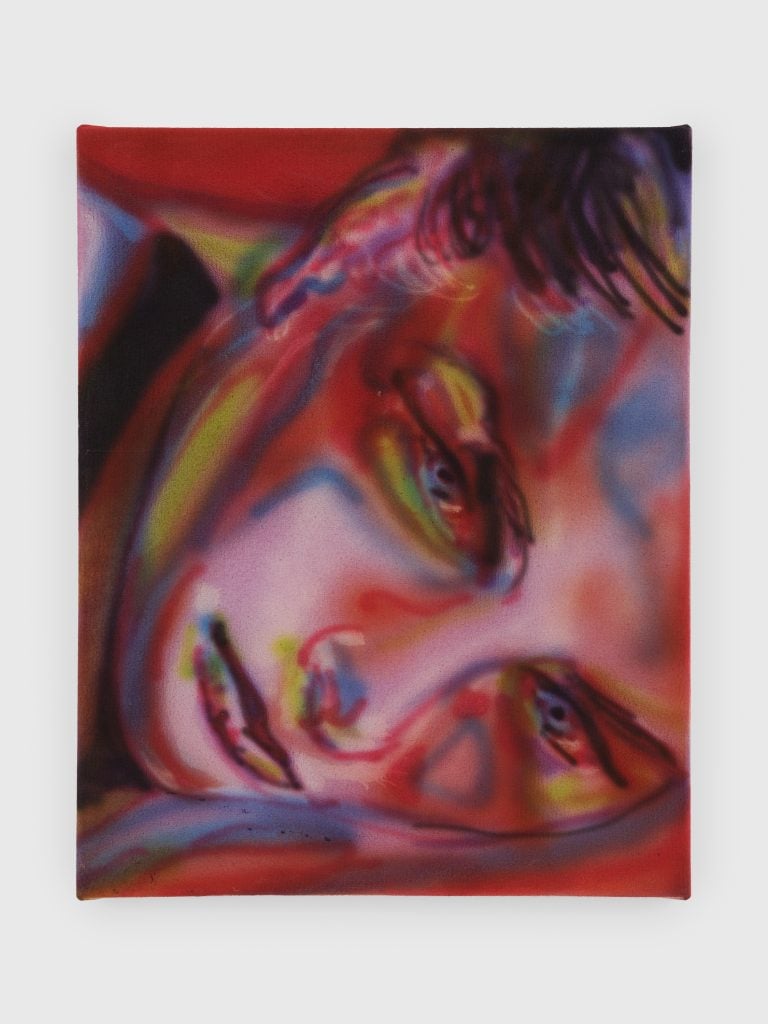

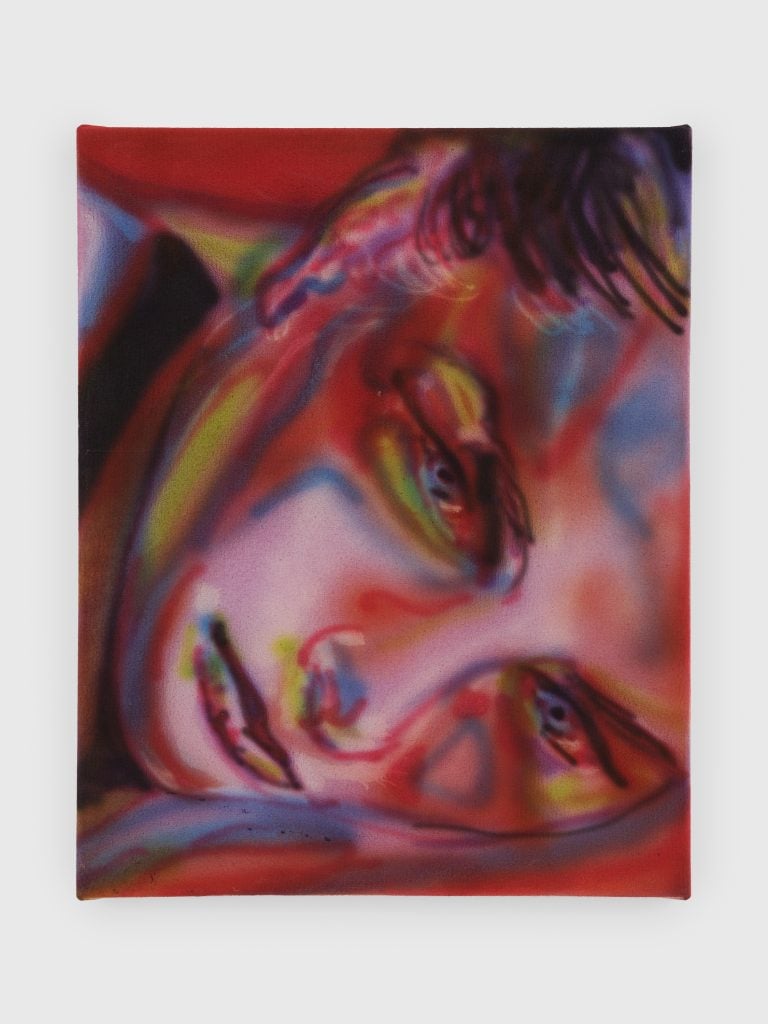

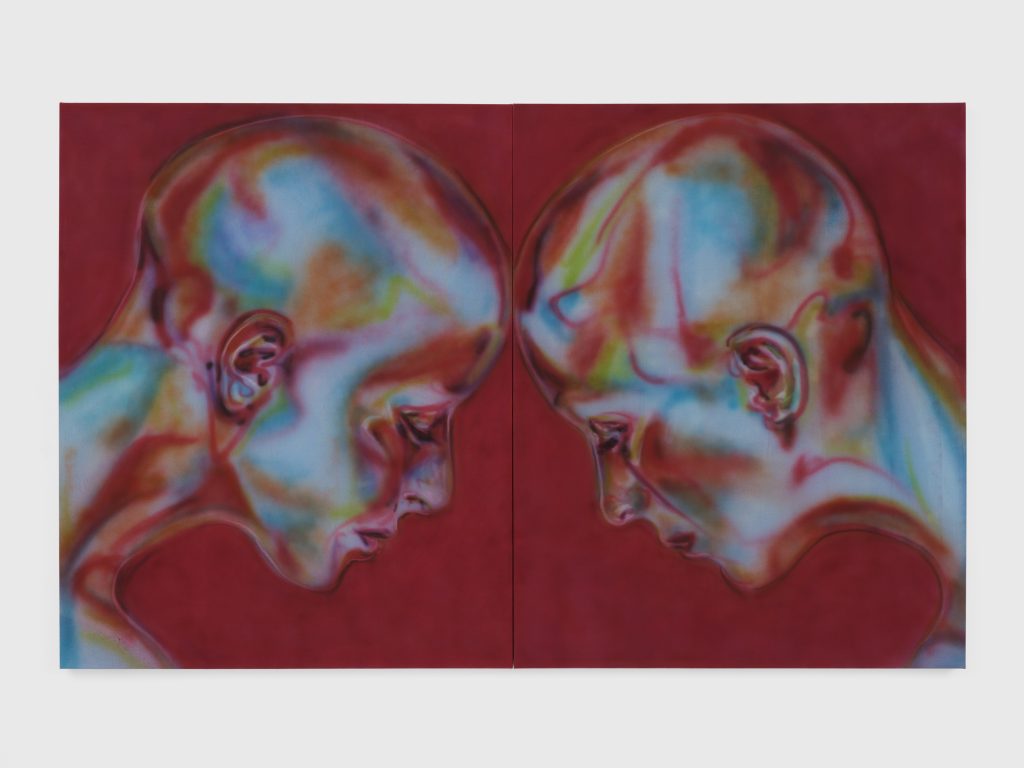

Katie Hector, Death makes angels of us all and gives us wings where we had shoulders smooth as raven claws (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Management, New York.

In the diptych Death makes angels of us all and gives us wings where we had shoulders smooth as raven’s claws (2024), featuring two figures oriented towards each other, foreheads just touching, the strength of the work lies in its ability to carry multiple readings simultaneously. It could be seen as the psychological self meeting its counterpart, id and superego, partners or friends or family members in a shared emotional moment. Each of Hector’s paintings manage to hold room for what the viewer brings to it, an effect of her process.

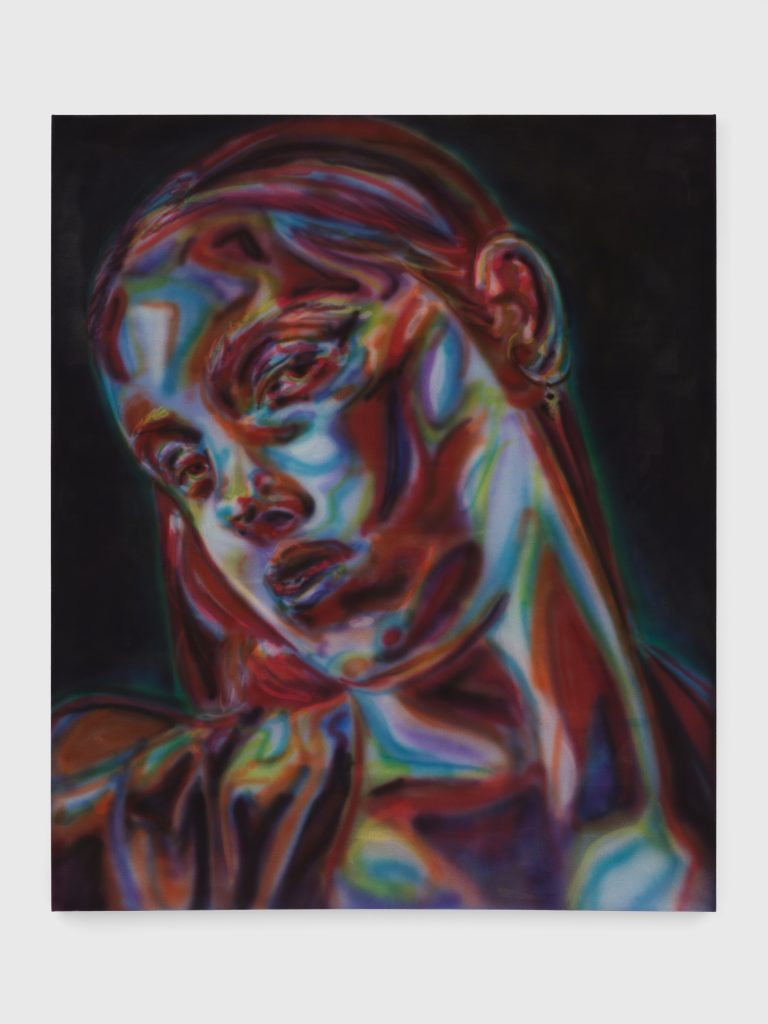

Katie Hector, Riley (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Management, New York.

Each portrait, or rather “portrait,” is an amalgamation of references, from casual screenshots off social media to well-researched photographs. The result for the viewer is a feeling of hazy recognition like you might remember whom you are reminded of if you keep looking a moment longer.

“I try to walk each portrait away from a conveyance of individuality and like it best when a finished work has many different points of access. That’s my hope for this body of work,” the artist explains. “I’m trying to open up portraiture and question if something akin to me can also feel familiar to you. Could a portrait of someone I know also feel like your sister, friend, aunt, or classmate? Can it activate your own story in your mind?”

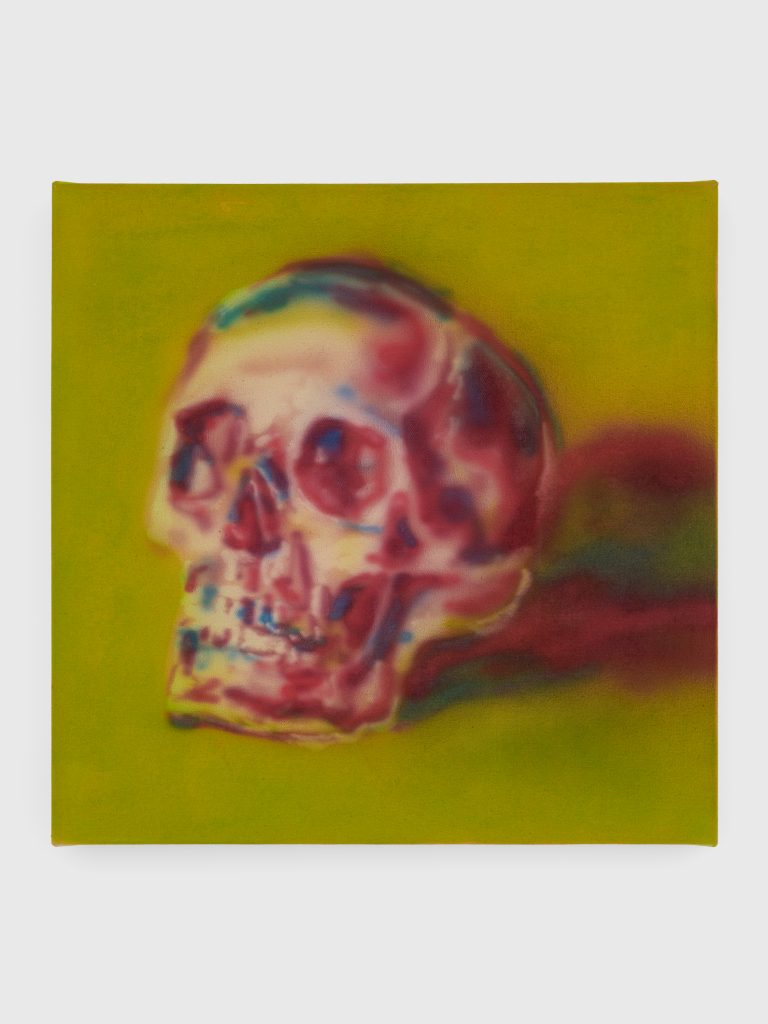

Katie Hector, Dead Head I (2024). Courtesy of the artist and Management, New York.

While the paintings in “Ego Rip” predominantly feature figures, two small-scale paintings operate as proverbial bookends, Dead Head I and Dead Head II (both 2024). Evoking the tradition of memento mori, both feature skulls; one hangs by the door and the other is tucked into a corner on the opposite side of the gallery space. Together these paintings act as cogent and poignant reminders that death is not simply a metaphor, but something we carry, a lens through which we catch glimpses of our own material being.