You can learn a lot about Kayode Ojo’s work by watching people interact with it. That’s especially true inside “EDEN,” his new exhibition at 52 Walker, New York, where visitors navigate intricate assemblages of stemware, jewels, and other expensive-looking wares with the trepidation of a tourist at Tiffany’s.

It’s funny at first. After all, most of the shiny objects that make up the artist’s sculptures are not genuine items of luxury, but budget imitations—rhinestones, not diamonds; acrylic, not crystal. Then again, that’s the rub: even if these things are cheaply made, they have, through the context of the gallery, been turned into art. And in this case, that art costs between $20,000 and $75,000.

This, of course, is the syllogistic logic that’s always defined the readymade, and Ojo knows it. The New York-based artist directs attention to it with the captions for his sculptures, which reproduce the exact descriptions of his various materials as he finds them at Amazon, Ikea, or elsewhere. Most are larded with generic, search engine-optimized terms that Ojo, who once worked as a keyword cataloguer for an image licensing agency, sees as a form of poetry. “Heavy Duty Toy Metal Handcuffs with Keys – 6 PACK Stainless Steel Bulk Fake Hand Cuffs Accessories Supplies for Kids Police Pretend Role Play, Adult Party Favors” reads the medium line in one.

“The context of the gallery is so important,” Ojo said, looking around the space at 52 Walker. “It’s the whole thing, when you really think about it.”

Installation view, “Kayode Ojo: EDEN,” 52 Walker, New York, October 27, 2023 – January 6, 2024. Courtesy of 52 Walker.

Following a string of exhibitions in Berlin, Venice, and Washington, D.C., “EDEN” is the 33-year-old’s first New York solo show in several years. His work makes sense in the city, especially in the uber-gentrified neighborhood of Tribeca, where luxury retailers share blocks with street vendors hawking knockoffs of their products.

As he spoke, Ojo was sitting in a back office at the gallery that he’s turned into a temporary studio, though it looks more like a staging area for a showroom. Next to him are various pieces of chrome furniture, instrument cases, and racks of glittering cocktail dresses. Ojo explained that he spent more than a year and a half prepping for “EDEN,” but all the actual artworks were created on-site days before the opening, when he piled a smattering of previously acquired materials in the front of the gallery, then meticulously tested them, one-by-one, in different combinations throughout the room.

The vast majority of items didn’t make the cut. Others were added at the 11th hour. “Free two-day shipping!” Ojo joked, underscoring one of the central aspects of his practice: he is an eager participant in the same consumer economies that his artwork calls out.

Installation view, “Kayode Ojo: EDEN,” 52 Walker, New York, October 27, 2023 – January 6, 2024. Courtesy of 52 Walker.

For Ojo, installation requires some trial and error. He stacks, wraps, and drapes his materials, but never adheres or fastens them together—not even when he incorporates tools of bondage. This time around, the process was particularly “arduous and heavy,” said Ebony L. Haynes, 52 Walker’s director and a longtime friend of the artist’s. “We have lots of conversations about what we want to say or what he’s thinking through, then it becomes a subtractive process. But nothing comes easy. Nothing was pre-planned.”

What was Ojo looking for when, for example, he swapped out sets of champagne glasses for the umpteenth time during a late-night installation session? Haynes, who has curated the artist’s work on several occasions in the past, couldn’t say. “In the moment, it seemed clear. But to put it into words…” She paused. “I don’t know how to summarize what he was going for.”

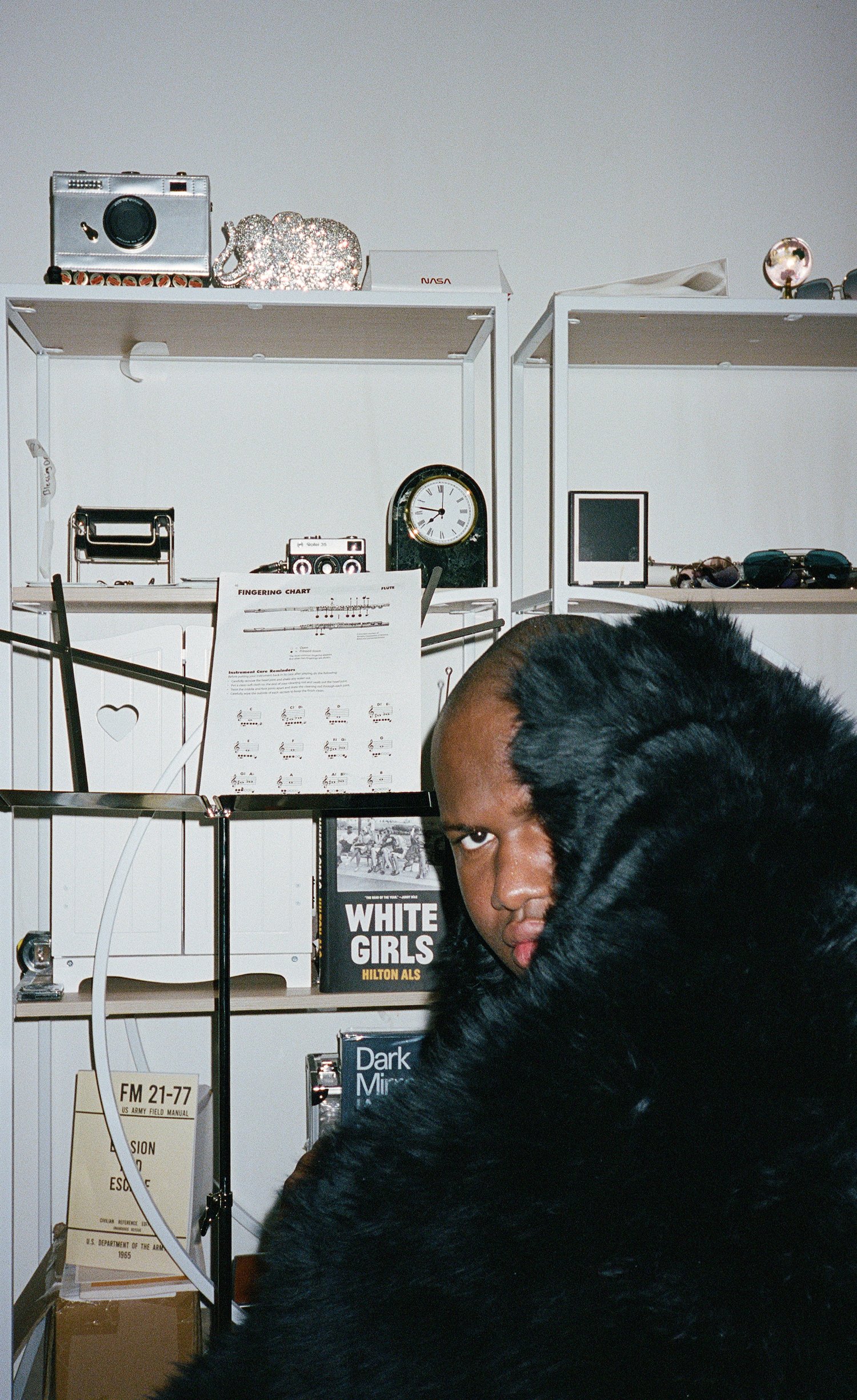

A photograph of Kayode Ojo’s studio, 2023. © Kayode Ojo. Courtesy of the artist and 52 Walker.

The artist doesn’t know how to summarize his work either, it turns out—or at least he was reticent to do so at multiple points during the interview. “If I knew why I made this work, I would maybe just write something instead,” he replied dryly at one point. “If I knew why I was making it, maybe it wouldn’t even exist.”

Whether Ojo is truly unsure of his intentions or just being elusive isn’t clear. It’s not the only thing he says that seems at odds with his art. On some level, he’s undoubtedly trying to preserve the interpretability of his works, which insist on ambiguity despite being comprised of coded innuendos and class signifiers. In The Brick (2023) for instance, a harmonica, a camera, a cocktail shaker, and a clock sit atop a mirrored, Haim Steinbach-looking shelf. Individually, these items are innocuous enough, but lined up, they tease different evocations in each other: the camera starts to feel a little prurient; the shaker looks violent. Is this collection of commodities supposed to tease our desire to spend or other, darker compulsions? Ojo, for his part, doesn’t tip his hand.

Installation view, “Kayode Ojo: EDEN,” 52 Walker, New York, October 27, 2023 – January 6, 2024. Courtesy of 52 Walker.

Even when the artist includes authentic pieces of high-end merchandise alongside their bargain-bin counterparts, he does so without distinction. Ojo isn’t interested in debasing his expensive objects any more than he is in reclaiming the cheaper ones as kitsch. “That’s not necessarily my focus,” he said when asked about the worth of some of the products in “EDEN.” “It’s something I’d prefer to leave as it appears.”

And yet, regardless of his items’ original value, there is an austerity to the way he stages them that is synonymous with wealth. The coupe glasses that form a pyramid in We thought it might go the other way (2023) are laboriously spaced out and aligned; so are the chains that hold up the chandelier lights of Comfort (2023). There’s not a smudge or fingerprint on anything, a minor miracle given the shine of it all. Eventually, the fastidiousness starts to feel like fetishism: Ojo’s readymades are clean to the point of seeming dirty.

On this point, he might disagree—though it is not the first time he’s heard the suggestion. “One thing I do think is funny is when people call the work ‘sexy,’” he said. “I still don’t know what this means, the idea of an object being sexy…”

Installation view, “Kayode Ojo: EDEN,” 52 Walker, New York, October 27, 2023 – January 6, 2024. Courtesy of 52 Walker.

Growing up in an evangelical Christian home in rural Tennessee, Ojo didn’t have access to fine clothes and precious stones, and he didn’t aspire to, either. The interest in commercial objects has always been about their formal properties first, their symbolic value second, he explained.

When this topic came up, Haynes recalled a story she’d heard about the time Ojo went out for middle school marching band and he was brought into a room to pick out one of the many instruments laid out. Ojo settled on the flute because it was a “shiny thing in a case that’s lined with velvet,” Haynes said. “It looked so pretty and rich.”

The choice wasn’t exactly practical. “He picked it and then he realized very soon that he should have picked something else because no one can hear a flute in a marching band,” she explained, giggling at the image she had conjured. “I think that says a lot about Kayode.”

Installation view, “Kayode Ojo: EDEN,” 52 Walker, New York, October 27, 2023 – January 6, 2024. Courtesy of 52 Walker.

Maybe more telling is Ojo’s integration of the instrument in his sculpture Embouchure (2023). In that piece, roughly three dozen flutes are connected with a pair of parallel chains suspended from the ceiling. At first glance, the sculpture looks like a playground apparatus—as sweet and innocent as the marching band story. But linger a minute longer, and other connotations may come to mind. Just read the materials caption: “Glory Closed Hole C Flute With Case, Tuning Rod and Cloth, Joint Grease and Gloves Nickel Silver, WXJ13 Swivel Clasps Lanyard Snap Hook Lobster Claw Clasp and Keychain Rings, 55 Pieces.” In Ojo’s show, as in the garden after which it’s named, beauty is inextricable from sin.

“Maybe [the work] does give people what they want,” Ojo eventually conceded. “It gives you what you want but doesn’t quite tell you why you want it.”

“Kayode Ojo: EDEN” is on view now through January 6, 2024, at 52 Walker in New York.

More Trending Stories:

A Shipwreck Off the Coast of Colombia May Hold $20 Billion Worth of Treasure

Hot! How a Backyard Photographer Captured Some of the Most Detailed Images of the Sun

Chinese Artist Chen Ke Celebrates the Women of Bauhaus in a Colorful, Mixed-Media Paris Debut

A Centuries-Spanning Exhibition Investigates the Age-Old Lure of Money

Meet the Woman Behind ‘Weird Medieval Guys,’ the Internet Hit Mining Odd Art From the Middle Ages

Conservators Find a ‘Monstrous Figure’ Hidden in an 18th-Century Joshua Reynolds Painting

A First-Class Dinner Menu Salvaged From the Titanic Makes Waves at Auction

The Louvre Seeks Donations to Stop an American Museum From Acquiring a French Masterpiece