As one of the original Post-minimalists, Keith Sonnier is an artist associated with being at the heart of New York City’s experimental art scene. His first solo show in more than three decades, however, arrives at the Parrish Art Museum in Watermill, New York.

Yet in a way, this expansive survey chronicling the many chapters of Sonnier’s art is perfectly at home in the seaside town. His entire career has been an exercise in exploring contrasts.

Although well-known to European cognoscenti, Sonnier is surprisingly underappreciated in the United States, especially in comparison to other artists of his generation, including Dan Flavin, Eva Hesse, and Bruce Nauman. How can it be that Sonnier, whose practice not only involves the neon light works that bucked the conventions of traditional sculpture, but encompasses Arte Povera-esque experiments with silk, flocking, and bamboo, not to mention a collaborative project with NASA that featured sound and media transmission, could be missing from the contemporary survey?

That is something that guest curator Jeffrey Grove has set to remedy through the Parrish’s expansive survey, “Keith Sonnier: Until Today,” which opened in early July and runs through January 27, 2019.

Keith Sonnier’s Ba-O-Ba I (1969). Image Courtesy of the artist and Maccarone Gallery, NY/LA. © 2018 Keith Sonnier/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Indeed, Sonnier is being feted throughout the Hamptons this summer with a trifecta of shows. In addition to the Parrish, “Keith Sonnier: Dis-Play II,” is now on view at the Dan Flavin Art Institute in Bridgehampton, while the nearby Tripoli Gallery is wrapping up a four-week stint showing Sonnier drawings and sculptures, dubbed “Tragedy and Comedy.”

In the Parrish Museum’s ultra-modern, wood-and-steel space, Sonnier’s work takes over two small exhibition galleries, one large gallery space, and the main passageway that constitutes the “spine” of the building, where he has installed a site-specific work, Passage Azur.

Installation view: Keith Sonnier: Until Today, Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, New York, July 1, 2018–January 27, 2019. Photo: Gary Mamay.

Like much of his work, Passage Azur was originally inspired by his experiences outside the US. The spirals of neon tubing suspended from the museum’s ceiling are drawn from a trip to India, where he saw the Holi Festival, an orgiastic celebration of color, where people gather en masse and frolic, smearing each other with raw pigments.

Although his work is formally classified as Post-Minimal, or even Anti-Form, there is a distinct Pop sensibility that runs through the work, and a spirited commitment to revelry and indulgence that imbues him with a sense of confidence.

Keith Sonnier’s Catahoula (Tidewater Series) (1994). Courtesy of Keith Sonnier Studio, Photo: © 2018 Caterina Verde. © 2018 Keith Sonnier Studio/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

These qualities, according to Grove, are what makes Sonnier stand out among his more famous peers. Speaking to artnet News before the show opening, the curator explained that “the difference with Keith is that he has a willingness to expose himself to experimentation that a lot of his peers lacked. And that’s not a lack of rigor, that’s a confidence… a kind of quirky confidence that allowed him the freedom to expose himself to nontraditional materials that at lot of artists of his generation weren’t doing at the time.”

While many artists of the Minimalist era grappled with the conventions of sculpture by removing the pedestal and any sort of narrative association, Sonnier’s sensibility came out in a somewhat maximalist attitude. He wasn’t restricted to self-referential objecthood, straight lines, or industrially-milled materials.

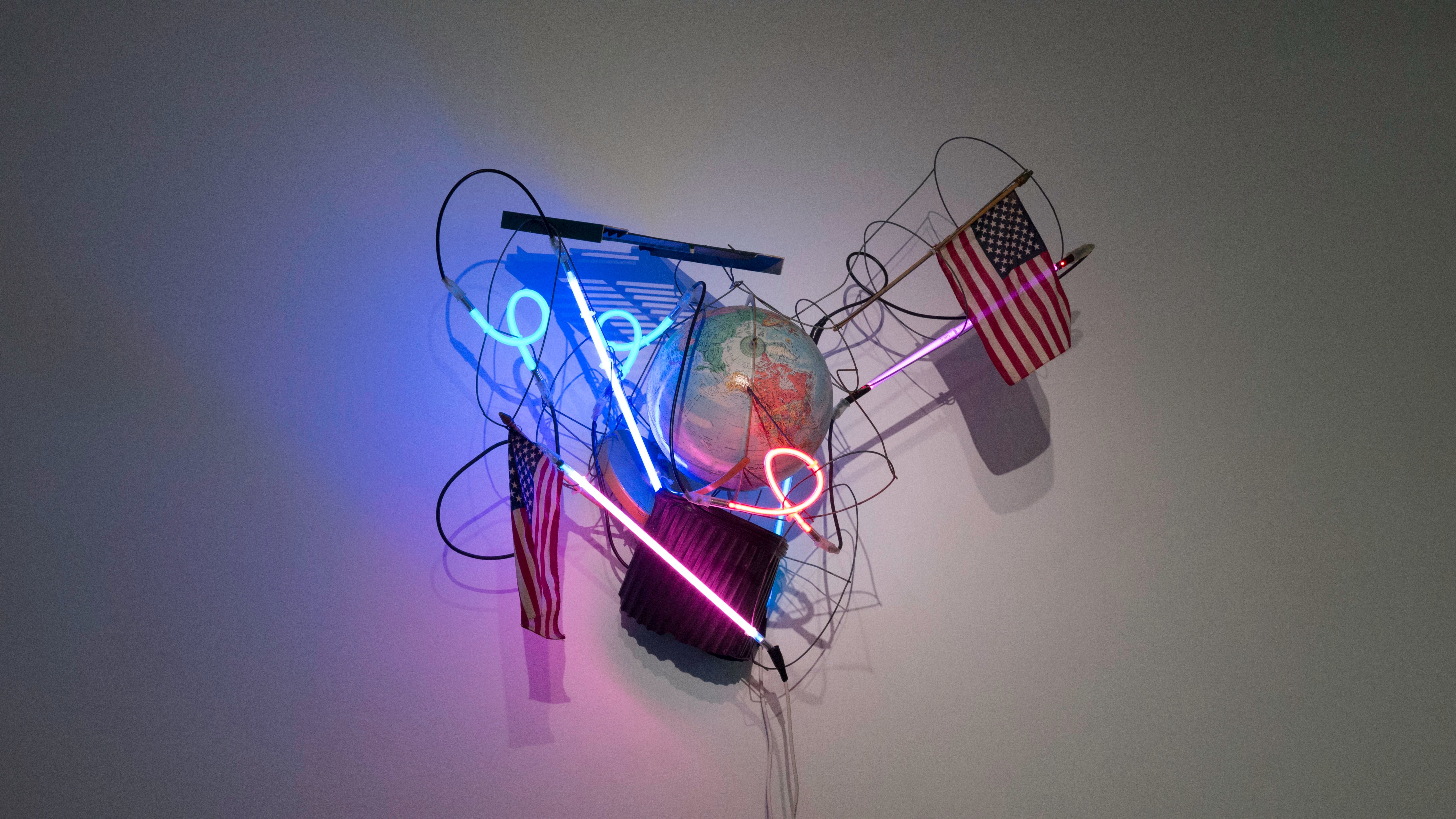

Keith Sonnier’s Syzygy Transmitter, Antenna Series (1992). Photo: © 2018 Caterina Verde. © 2018 Keith Sonnier Studio/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

Instead, he gathered cast-off materials like laundry baskets and ripped-up dresses his mother collected at the local gown-swap, incorporating the pink silk fabric into his work, and moving his works from the wall to the floor, letting them take on anthropomorphic qualities. This practice underscores something that Grove considered vital to highlight in his exhibition: “that [confidence] involves engaging with materials that some people might’ve coded as feminine, or sexual, or erotic… and a lot of male sculptors stayed well away from those associations.”

Sonnier’s often jumbled combination of materials is directly related to his childhood in the small town of Mamou, Louisiana, the heart of Cajun country. A potpourri of cultures and languages converged in the town; Roman Catholicism existed in harmony with debaucherous Mardi Gras celebrations. In an interview for the exhibition catalog, Sonnier describes the sight of parading horseback figures on Mardi Gras as an inspiration: “the costumes are out of the ordinary—they’re made almost to look like fantasy ghouls or elements from another world, but made out of very simple materials.”

Keith Sonnier’s Deux Pattes (1981). Image courtesy Keith Sonnier. Photo: © 2018 Caterina Verde. © 2018 Keith Sonnier Studio/Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY.

This eye for humble materials is felt in the way that some of Sonnier’s sculptures are literally buzzing with an electrical current, emitting a nebulous neon glow, even as their armature is completely exposed.

His turn from abstract sculpture toward figuration is evident in works like Deux Pattes, an aluminum-and-steel skeleton that evokes the image of a speed skater, one leg fully extended, the other bent at the knee. It also calls to mind an emblematic sculpture of Futurism, one of the first to harness the dynamism of a body in motion: Umberto Boccioni’s Unique Forms of Continuity in Space from 1913.

Installation view: “Keith Sonnier: Until Today,” Parrish Art Museum, Water Mill, New York, July 1, 2018–January 27, 2019. Photo: Gary Mamay.

For a brief period of time, Sonnier’s work veered toward politics, telling artnet News, “the piece with the flag, War of the Worlds, it’s definitely about politics and war—quite frankly, it looks like a bunch of space trash floating in the atmosphere.” Maybe so, but it is beautiful trash indeed.

While he’s not showing any signs of slowing down anytime soon, Sonnier’s is planning for the future, hoping to establish a foundation in Bridgehampton, cementing his legacy in the landscape of contemporary art.