Art World

Artist’s Depiction of Police Brutality Sparks Boycott at St. Louis Museum

Artist Kelley Walker issues apology over images of police brutality smeared with chocolate.

Artist Kelley Walker issues apology over images of police brutality smeared with chocolate.

Brian Boucher

Some members of the black community in St. Louis, Missouri, are up in arms against an exhibition they find deeply offensive for its inclusion of images of African-Americans.

The exhibition, “Kelley Walker: Direct Drive,” was organized by Jeffrey Uslip, chief curator at the Contemporary Art Museum, who has been in the position since January 2014. The works include images of police brutality toward Civil Rights protesters, silk screened with smeared white and dark chocolate.

Walker’s work “interrogates the ways a single image can migrate into a number of cultural contexts,” writes the museum, adding that Kelley “has explored the manipulation and repurposing of images in order to destabilize issues of identity, race, class, sexuality, and politics.”

Several works in particular, including the multimedia Black Star Press, do not rest well with all viewers. As the museum describes it:

A parallel to Warhol’s canonical 1964 painting Race Riot, Walker’s Black Star Press series comprises images of racial unrest that have been digitally printed on canvas, silkscreened with melted white, milk, and dark chocolate, and rotated in ninety- degree increments. These manipulations mask and partially censor the act of police brutality with a perishable material as well as alter the power dynamic between the image’s subjects.

The show opened almost exactly two years after the police shooting of unarmed black teenager Michael Brown in nearby Ferguson, which led to several nights of sometimes destructive demonstrations in the city and was a key spark for the Black Lives Matter movement.

“This city is being ripped apart,” gallery owner Philip Slein told Art in America at the time. “A chasm is developing in this already incredibly racist state.”

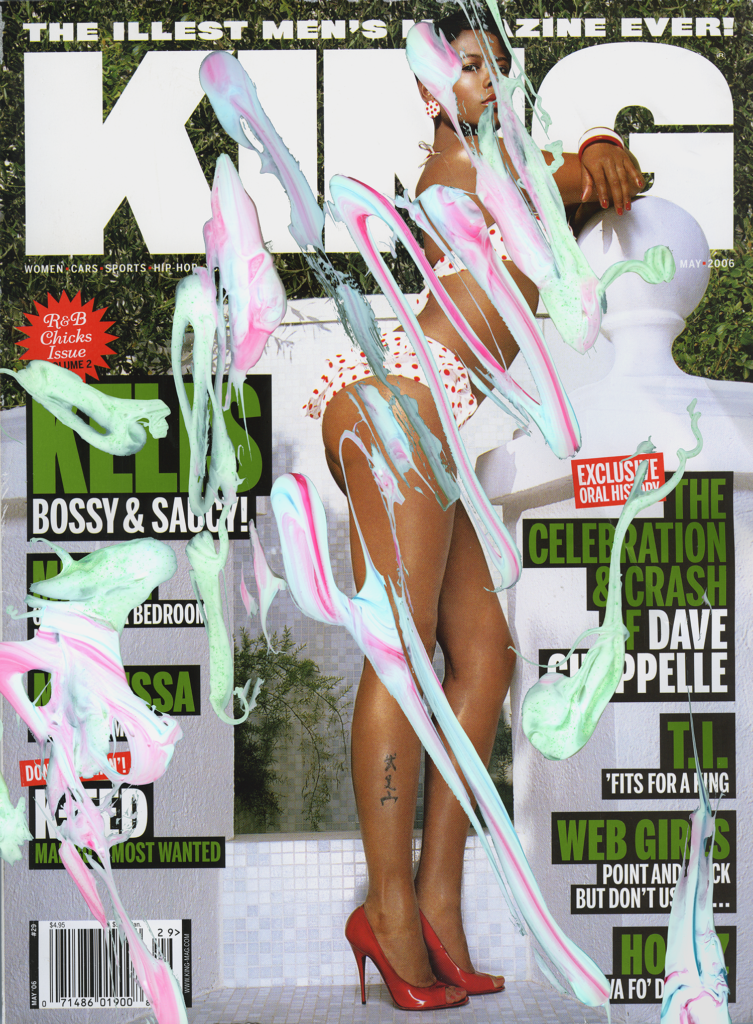

Kelley Walker, schema; Aquafresh plus Crest with Whitening Expressions (Kelis), 2006. CD Rom with color poster, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist; Paula Cooper Gallery, New York; Thomas Dane Gallery, London; and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne.

Activist and artist Damon Davis has spoken out about the Walker show on Facebook:

Kelley Walker, a white man, takes images of black women, and photos of black people being attacked by police and dogs, and smears toothpaste and chocolate on the images. This work is offensive to black people, black women in particular, and the black struggle for freedom that we and our ancestors have been engaging in since this country was founded.

Davis creates activist works like an edition of prints showing women of color with fists raised (dedicated to Sandra Bland), a mock street sign reading “cops not welcome,” and images of Tamir Rice and Trayvon Martin.

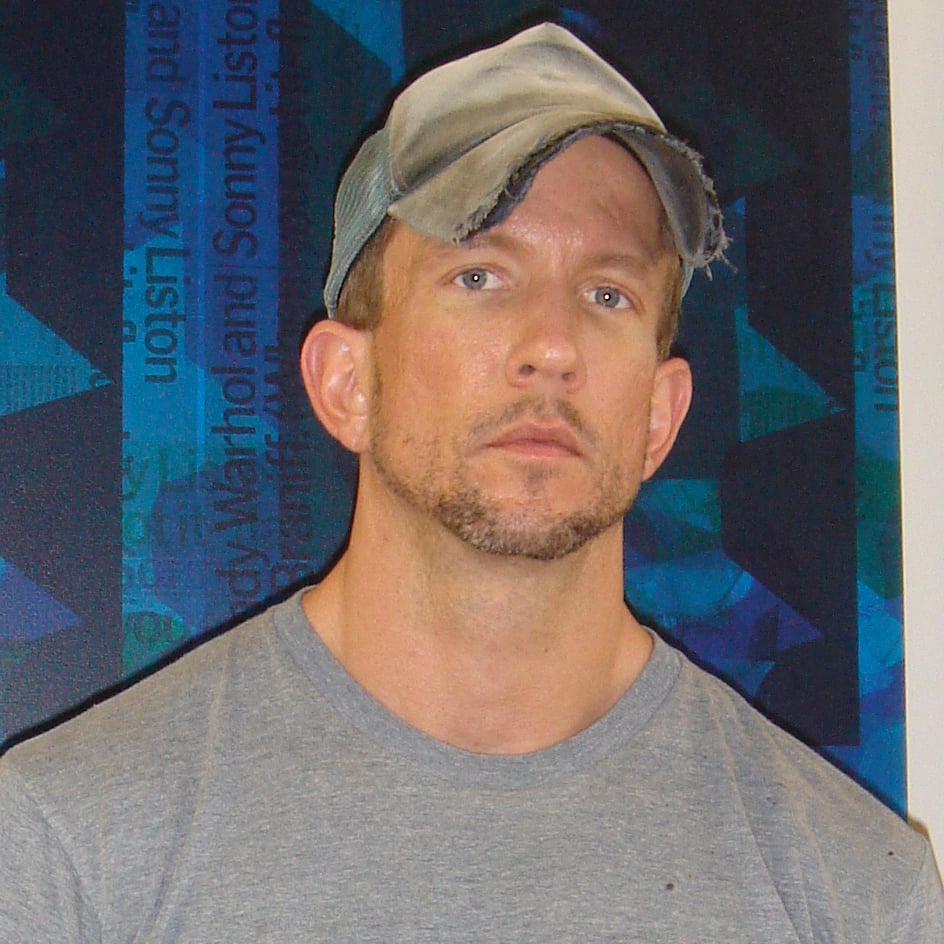

Kelley Walker. Photo Meredyth Sparks, courtesy Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis.

Several black staffers have called for Uslip’s resignation. De Andrea Nichols, community engagement manager, posted to Facebook a strongly worded open letter signed by her, along with museum educator Lyndon Barrois Jr. and Victoria Donaldson, the museum’s visitor services manager.

They also call for the removal of several works they call “untimely and insensitive.” Walker’s work, they contend, “triggers a retraumatization of racial and regional pain.” Citing ongoing police killings of black men, they say that the museum’s display of the work “positions the museum and its staff in implicit support and perpetuation of these societal ills.”

In just the last few days, Terence Crutcher, an African-American man, was killed on video by police in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and in Charlotte, North Carolina, Keith Lamont Scott was gunned down by officers who say he brandished a gun; the authorities have declined to release video of the incident.

The staffers also say they expressed serious reservations about the work to museum leadership during the planning for the show.

A September 17 artist talk only inflamed matters further, when Davis challenged Walker to explain his imagery.

“When confronted with an actual black person, Walker became flustered and angry and had no actual answer for why he was using these images,” Damon Davis wrote. “When he couldn’t answer my questions, the curator, Jeffrey Uslip, interjected and tried to explain for him. Walker and Uslip never answered my questions, and were both rude and condescending to myself and multiple people that asked questions that both related to race and not.”

In an echo of public demands for police footage of the killings of African-American citizens, the open letter from museum staffers demands the publication of video of Walker’s talk and his interactions with the audience.

Museum director Lisa Melandri took the unusual step of offering an unreserved apology.

“I acknowledge and recognize that was a difficult situation and that people who were asking questions weren’t given answers,” Melandri told the St. Louis American. “For that, I absolutely apologize. This is a space that welcomes questions and people who expect answers to their questions.”

Walker has also issued a statement, provided to artnet News by the museum:

I deeply regret that a great deal of anger, frustration and resentment have developed in the St. Louis community as a result of my failure to engage certain questions from the audience during the public lecture at CAM last Saturday. The concerns were legitimate, so I regret that I did not answer them adequately at the time.

The KING magazine covers and Black Star Press works—two series among a broader body of work that deals with the circulation and recycling of images—are at the center of this controversy as they explore the politics of race. Although the works date from the early 2000s, they have been exhibited many times since then and I have also spoken about them in depth in prior artist talks and interviews, I should have been much clearer and more articulate about them. Given the painful recent history of the city, as well as the much longer history of violence and injustice directed at its African-American community, I should have been better prepared to address the subject matter.

I am a staunch advocate of social equality and civil rights in America. I am also an artist who seeks to create thoughtful, sometimes difficult dialogues about these issues. I have always hoped that these works, and the exhibition as a whole, would provide a forum for a conversation about the way American society gets represented in the media as images shift from context to context (newspapers, magazines, film, TV, etc.) and about how the representation of the body, particularly of the black body, is an exceedingly complex topic in American art and culture.

I hope that the St. Louis community will give my exhibition a chance to generate this conversation. I also hope that the community, as well as the museum, its director and its staff, will understand how much I regret the misunderstanding and the ill feeling caused thus far.

Melandri spoke to artnet News by phone Friday morning, after a panel discussion that, she said, started at 7 p.m. and lasted until 10:30, to discuss the calls for removal of the works and for Uslip’s resignation.

“We made a commitment to listen to the community and weigh the consequences of the next step and the consequences of our actions, understanding the pain and hurt of our local community as well as the global implications of what it means to remove artworks from what we deem a safe space for ideas,” said Melandri.

“Kelley Walker: Direct Drive” is on view at the Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis through December 31.