On View

Playful Pop Surrealist Kenny Scharf Gets Serious

Think you know Kenny Scharf? A show at the Brant Foundation may make you think again.

More than four decades into painting, Kenny Scharf, a visionary of Pop Surrealism and a fixture of New York’s downtown art scene, is at the pinnacle of his career. The artist’s top 30 auction sales have all transpired since 2020 and this past May, an aerosol artwork sprayed on-site for a benefit auction sold for a record $1.1 million. Now, with three major exhibitions currently on view in New York City, Scharf’s dynamic, colorful works are being celebrated like never before.

After enrolling in New York’s School of Visual Arts in 1978, Scharf became pals with street artists Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. The rest is history, as they say. Throughout the 1980s, he spent his time orbiting Warhol, painting the streets, and getting freaky at Manhattan’s nightclubs. He became known for his vibrant, distorted faces that are usually laughing or smiling, which are exemplified in a recently unveiled show at Lio Malca’s 60 White gallery. Meanwhile, a suite of new works joyfully commemorating the year of the dragon, are on view at the Lower East Side gallery TOTAH.

A survey at New York’s Brant Foundation, however, emphasizes the angst that has been brewing just beneath his jocular figures all along.

A view of the exhibition’s final, bottom floor. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

Brant co-curated the three-floor extravaganza alongside dealer Tony Shafrazi. Together, they supplemented their collections with Scharf’s holdings, plus loans from museums and other collectors, like Larry Warsh and Robert De Niro. Scharf hasn’t done anything this big since his exhibition at the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Monterrey in 1995.

“I’ve been wanting this, obviously, for many, many years,” he said over Zoom.

“I think some people might dismiss the art as just fun and light,” Scharf continued. “I can’t control what people think—and if they choose not to look further. But I think when you see it together in this mass, it might change your mind.”

Installation view, with The Days of Our Lives (1984) at center. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

At the show’s VIP preview, Scharf said it was emotional to encounter so many works he hadn’t seen in decades. “Some of this stuff goes on auction over the years, and then you don’t know who owns it,” he said. Brant located Scharf’s scattered treasures. Some, like The Days of Our Lives (1984), proved even wilder than Scharf remembered.

“I was just going nuts,” he said. “It’s so liberating to be able to make a painting and not care at all what a painting is supposed to be, or how you’re supposed to be.”

Guests are advised to start on the show’s top floor, and descend from there. Each level explores a running theme in Scharf’s practice, starting with the cartoon family the Jetsons before moving through portals, jungles, and portraits. Works from the 1970s through the ’90s appear on each floor. Casual fans, however, would have a hard time attributing some of the earliest paintings on offer to Scharf.

A view of the Jetsons floor. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

“I was just thinking about the painting Barbara Simpson’s New Kitchen,” he said regarding one 1978 work. He read the Guardian‘s recent interpretation that the titular character has tamed the dragon in her kitchen. “That’s not it at all,” Scharf said. “She’s just happy about her new kitchen and showing it off, despite the fact that there is a dragon right in your face. She’s ignoring it.”

Scharf was raised in California’s San Fernando Valley during the environmentalist movement’s advent, in the 1960s. “I made up my mind very early [that] we need to harness solar and wind, and we have to get off petroleum,” he said. The dinosaurs that appear throughout his work reference fossil fuels. Growing up, Scharf found the Valley’s air barely breathable. “I remember talking to my parents and going, ‘God, my lungs hurt today,’” he said. His suburban family, however, mostly cared about keeping up with the Joneses.

Kenny Scharf, Barbara Simpson’s New Kitchen (1978). Courtesy of the Brant Foundation.

“It made a strong impression on me, the hypocrisy of how you can just live and ignore stuff that’s right in your face,” he said. That message has only intensified 45 years on. “But if we got our brand new kitchen, we’re cool with that.”

Scharf has also famously upcycled the now-obsolete appliances that powered the 1980s and 1990s. This part of his practice, he said, is “like my fantasy idea of what an artist is and how an artist lives.” If you’ve ever ridden in one of his cars, then you understand how Scharf’s hand can elevate even the simple experience of sitting in traffic.

The Dino Phone. Photo: Vittoria Benzine.

Several answering machines appear among the show’s maximalist boomboxes, TVs, and calculators. One still holds a taped message from Haring, though Scharf can’t remember which. But, he definitely had regular conversations on the Dino Phone while living one block north of the Brant Foundation throughout the mid-’80s.

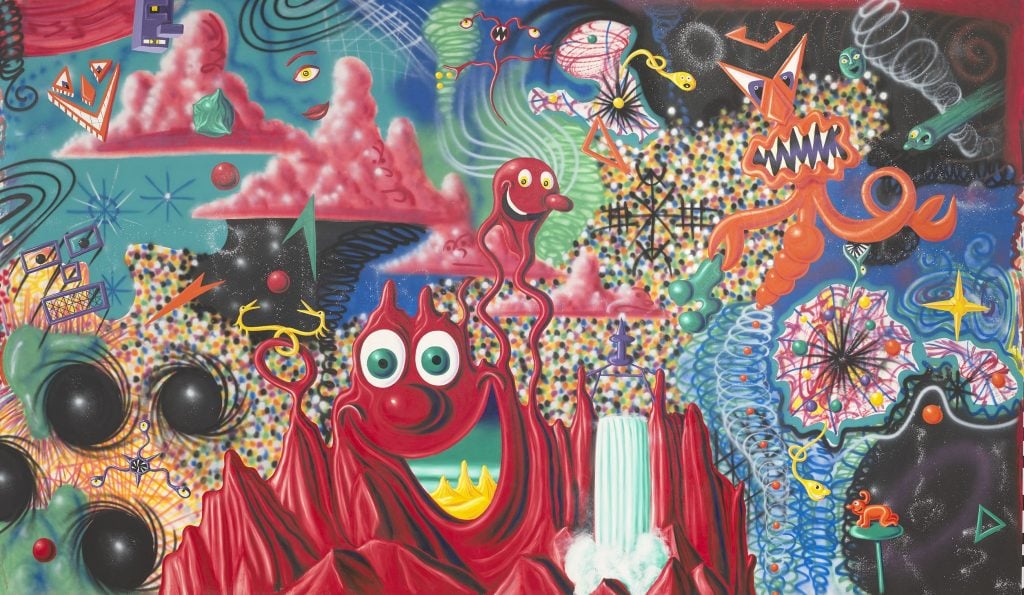

The Brant survey’s second floor features its banner image, and largest artwork, When the Worlds Collide (1983–84). The Whitney loaned the foundation this oil and aerosol painting, which appeared in the museum’s 1985 Biennial. Brant and Shafrazi received fellow downtown royalty like Charlie Ahearn in front of this piece during the VIP opening. But, amidst all the artwork’s excitement, Scharf pointed out one tiny detail—a Keith Haring “Radiant Baby” in its lower right corner.

The middle floor. Photo: Tom Powel Imaging.

“I had no studio,” he recalled of the moment in which he executed this tableaux. Haring, traveling in Europe, let Scharf use his SoHo space. Scharf added the baby glyph as a thank you.

One year prior, on a flight to join his Brazilian artist Bruno Schmidt for the country’s Carnival, Scharf met his wife Tereza Goncalves. He soon moved to a stretch of Brazil’s coastal rainforest. He painted there prolifically, living alongside fisherman who asked him if there was a moon in New York, too.

“I was just getting this notoriety—hanging out with Warhol and going to parties, blah, blah, blah,” he said. “Then all of a sudden, I was there in a place that had no electricity.” Scharf, who went to high school in Beverly Hills with celebrity offspring, felt leery around fame. He wanted to be taken seriously, and wasn’t sure his rockstardom helped. Neither did his authentic artist antics, though. When he and Goncalves showed up to the 1985 Whitney Biennial in a fringed outfit joined at the leg, the guests in black tie all rolled their eyes.

Kenny Scharf, Juicy Jungle (1983-84). Photo: Tom Powel Imaging

Fortunately, Scharf maintained his ties to New York while living in Brazil. Haring visited frequently. Scharf had copied Rousseau paintings extensively as a kid, dreaming of lush landscapes beyond arid SoCal. But jungle iconography entered his oeuvre afresh in the rainforest, as Scharf doubled down on environmentalism by partnering with the World Wildlife Fund. “I wish I could say we made a big difference,” he said, but matters have only worsened. Of all his tropical artworks from this era, Scharf considers Juicy Jungle (1984) the most iconic.

He moved back to L.A. in 1999. In an effort to establish community, he invited friends to sit for Old Hollywood–style portraits in his studio. Selections from this vast series round out his survey’s final floor—including the only one not painted from an original photo. Scharf pilfered his Patti Smith source image from Newsweek as a teen. At long last, he thinks, these portraits—like his early paintings—are getting their due.

One wall in the final floor’s portrait gallery, featuring Patti Smith at top. Photo: Vittoria Benzine.

“You can’t do anything about the time,” Scharf said. “Artists usually are ahead of their time.” Sure, he’s enjoyed Brant and Shafrazi’s longstanding support, but he always felt alienated by the art world’s more academic bigwigs. Based on the attendees at this survey’s dinner, this show may change that.

“Everything will catch up,” Scharf added. “Just be alive.”

“Kenny Scharf” is on view through February 28 at the Brant Foundation, 421 East 6th Street. “MYTHOLOGEEZ “is on view through December 7 at TOTAH, 183 Stanton Street. “Space Travel” is on view through January 27 at 60 White, 60 White Street.