Books

More Than a Muse: A New Biography Casts Kiki de Montparnasse as a Leader in the Heady Art Swirl of 1920s Paris

You might not know much about Kiki de Montparnasse, but a new book paints her as an influential figure of the Parisian avant-garde.

You might not know much about Kiki de Montparnasse, but a new book paints her as an influential figure of the Parisian avant-garde.

Sarah Cascone

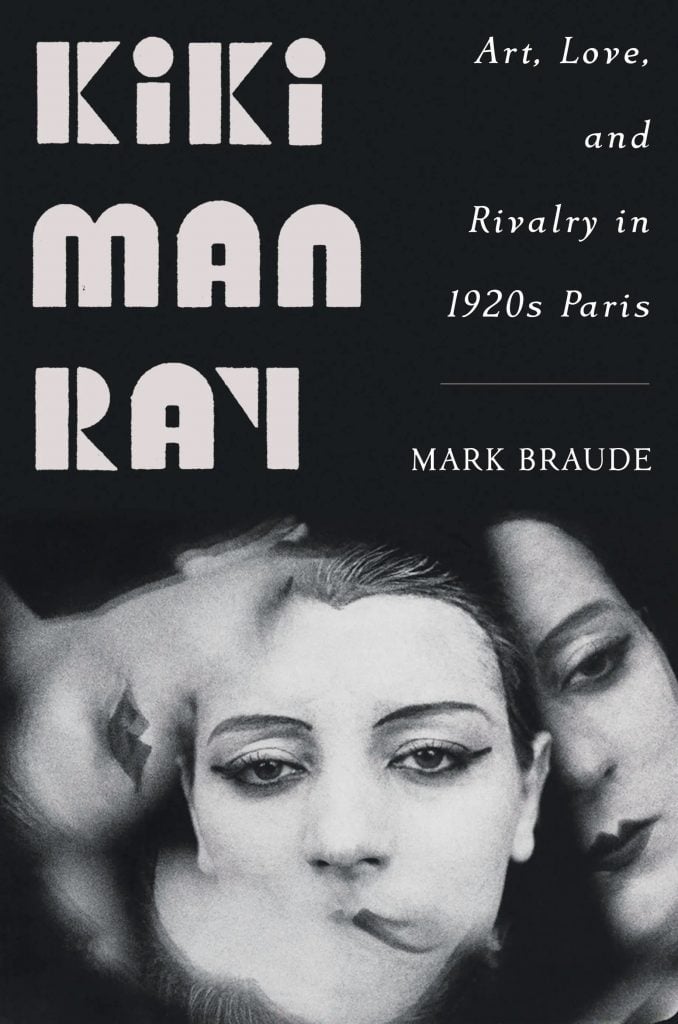

If you know the name Kiki de Montparnasse, it’s probably as the subject of the famed 1924 Man Ray photograph Le Violon d’Ingres. The Surrealist masterpiece shows De Montaparnasse’s naked back marked in the dark room with the shapely f-holes of a violin, wittily comparing the curves of the female form to the string instrument.

Last May, a print of the image became the most expensive photograph ever to sell at auction, bringing in $12.4 million at Christie’s New York. (De Montparnasse’s own auction record is a still-respectable €19,275 [$23,406], set in 2021 at Fauve Paris for the 1927 painting L’acrobate, according to the Artnet Price Database.)

A model to a slew of major artists, including Alexander Calder, Francis Picabia, and Chaïm Soutine, to name just a few, De Montparnasse was Man Ray’s muse and lover for eight years, from 1921 through ’29.

But a new biography of the woman born Alice Ernestine Prin argues that she was in many ways the center of the Parisian avant-garde, highlighting her accomplishments as an actress, cabaret star, memoirist, and artist in her own right. Essentially, De Montparnasse was a talented multi-hyphenate who reinvented herself through an artistic persona—an act decades ahead of her time.

Man Ray, Le Violon d’Ingres (1924). Courtesy of Christie’s.

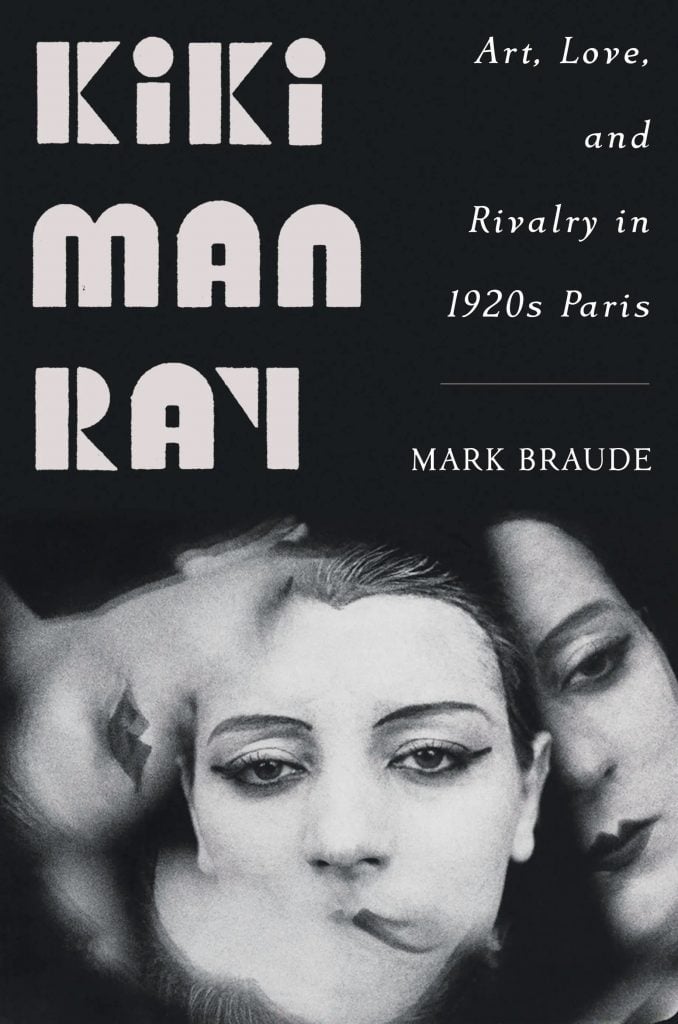

Written by Mark Braude, Kiki Man Ray: Art, Love, and Rivalry in 1920s Paris takes a deep dive into the life of this largely forgotten figure, from her impoverished and illegitimate origins to her literal crowning as queen of Montparnasse—Paris’s thriving artist quarter and nightlife hotspot—to her premature death at just 51, suffering from drug addiction and alcoholism.

It also charts her tumultuous relationship with Man Ray, as well as his origins as Emmanuel Radnitzky, born in Brooklyn. He, of course, became a leading light of the Dada and Surrealist movements, creating innovative photographs, paintings, and sculptures.

The two were surrounded by a milieu of now-famous names—the book’s pages are sprinkled with appearances by the likes of Amedeo Modigliani, Marcel Duchamp, James Joyce, Pablo Picasso, Gertrude Stein, Coco Chanel, and Peggy Guggenheim, to name just a few.

Man Ray, Noire et Blanche (1926). Photo courtesy of Christie’s Paris.

The book’s biggest takeaway is that while one could certainly make a case for De Montparnasse as a pioneering performance artist, her ephemeral works were sadly created in an era that rendered them evanescent.

And as with so many women artists, De Montparnasse’s fame has faded in the decades since her death. But unlike paintings and sculptures, which are ripe for rediscovery, her primary medium of performance—the very nature of the work that made her the lifeblood of Parisian bohemia in the 1920s—makes it difficult for audiences to truly experience her art, or to understand its importance in her time.

Braude does an admirable job of trying to rectify that injustice. Here are just a few of the fascinating facts about De Montparnasse presented in his tome.

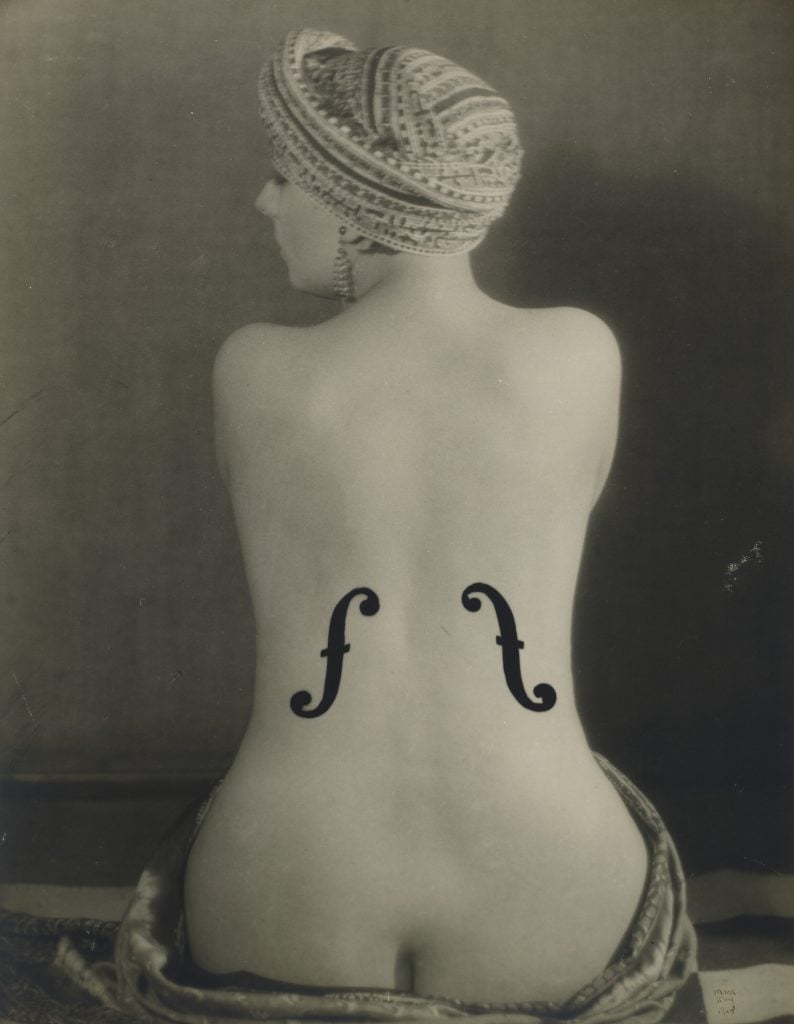

Maurice Mendjizky, Kiki.

Kiki de Montparnasse first moved to Paris at age 12. When she was 16, she started posing for artists after she lost her job at a bakery. To make money, she began posing nude for a sculptor who had been a regular at the shop.

After the initial discomfort wore off, De Montparnasse found the work both interesting and easy—but when her mother found out, she crashed the studio and threatened to alert the cops.

In her memoir, De Montparnasse said her mom called her a “miserable whore” and disowned her—irreversibly setting the young girl on her course in the art world.

Maurice Mendjizky, Kiki de Montparnasse (1921). Collection Fonds de Dotation Mendjisky- Écoles de Paris

In 1918, De Montparnasse, fresh off a case of the Spanish flu, fell in love with Polish artist Maurice Mendjizky. He did his first painting of her in 1919, and bestowed upon her the pet name Kiki, by which she would become famous.

“[It] stuck only because they liked how it sounded two quick breaths pushed with clenched tongue through bared teeth,” Braude wrote. “People used kiki as a bit of slang to describe all sorts of things: chicken giblets; someone’s neck (usually strangled or hanged); a cock’s crow; having a chat; having sex.”

Mendjizky and De Montparnasse lived together for three or four years, and there are six surviving oil paintings made depicting her, plus a drawing. Though De Montparnasse would credit the artist Moïse Kisling with “discovering” her, those pieces represent the true beginnings of the career of one of art history’s greatest muses.

Artists at the Jockey in Paris (ca. 1921). Back row from left to right: Bill Bird, unknown, Holger Cahill, Miller, Les Copeland, Hilaire Hiler, Curtiss Moffitt. Middle: Kiki de Montparnasse, Margaret Anderson, Jane Heap, unknown, Ezra Pound. Front: Man Ray, Mina Loy, Tristan Tzara, Jean Cocteau.

De Montparnasse acted as Man Ray’s assistant by managing his schedule and helping with translations when his French skills fell short—all while keeping house.

“Kiki did the shopping and cooking and serving,” Braude wrote. “She stretched their money to create fabulous Burgundian dishes with artfully prepared salads and expertly chosen cheeses, always paired with good wine and followed by brandy.”

Despite her humble beginnings and lack of means, De Montparnasse was blessed with a “seemingly innate ability to serve just the right food and drink according to the social situation, and to have attained that knowledge without money or much exposure to traditional forms of ‘high’ culture.”

Kiki de Montparnasse in the Cafe du Dome in Paris (1929). Photo by ullstein bild/ullstein bild via Getty Images.

In her memoirs, De Montparnasse wrote of singing for coins at bars as a child. But she was part of Paris’s artistic scene for several years as an adult before she started singing at the popular artist hangout the Jockey in 1924. Quickly, she became a famed chanteuse and local celebrity.

“Kiki’s shows were imbued with the spirit of artistic experimentation going on around her,” Braude wrote. “If a singing voice could smell, hers would be garlic hitting a pan’s hot butter and wine.”

Kiki de Montparnasse, L’acrobate (1927). The painting set an auction record for the artist with a €19,275 ($23,406) sale in 2021 at Fauve Paris.

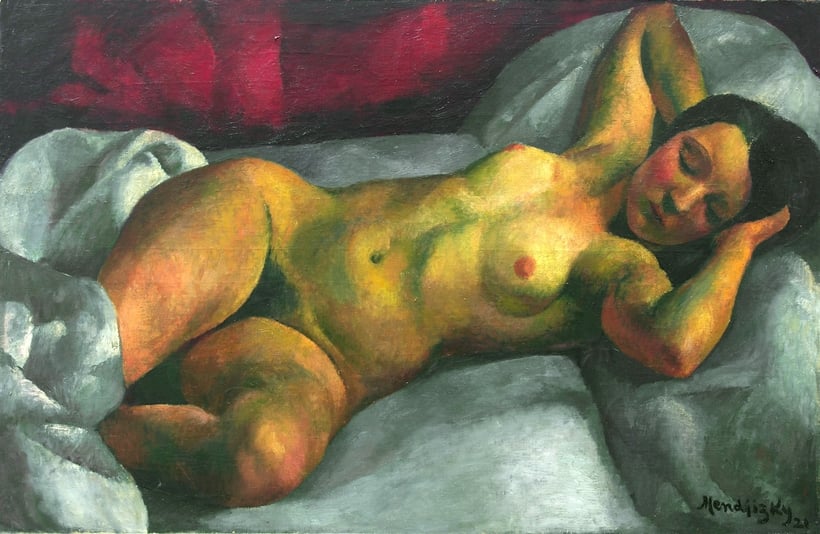

De Montparnasse began making art at an early age, drawing quick portraits of bar patrons and selling them to help make ends meet as a teenager. As she grew older, her work attracted the attention of the dealer Henri-Pierre Roché, who eventually bought 10 of her paintings.

In 1924, he wrote in his diary of purchasing a De Montparnasse watercolor he dubbed a “super-Matisse.”

Three years later, she had her first solo show at Au Sacre du Printemps in Paris, selling all 27 pieces on view—and getting good reviews to boot.

De Montparnasse’s first performance on film came in Le Retour à la raison, a hastily glued together three-minute film Man Ray made on two days notice for a Dada art show organized by Tristan Tzara in 1923. The event was marred by violence, with the police arriving after André Breton broke poet Pierre de Massot’s arm, and the night devolving into drunken fist fights in the streets.

Later that year, De Montparnasse traveled to New York, where she made a go of breaking into the movie business. The anecdotes vary, but for one reason or another, she returned to Paris without filming anything in the U.S.

There, she went on to have small parts in four pictures in quick succession, including Jaque Catelain’s feature film The Gallery of Monsters, credited as Kiki Ray. Her most prominent role came courtesy of Fernand Léger, in Ballet mécanique, in which De Montparnasse’s face is juxtaposed with close up shots of various objects and machines.

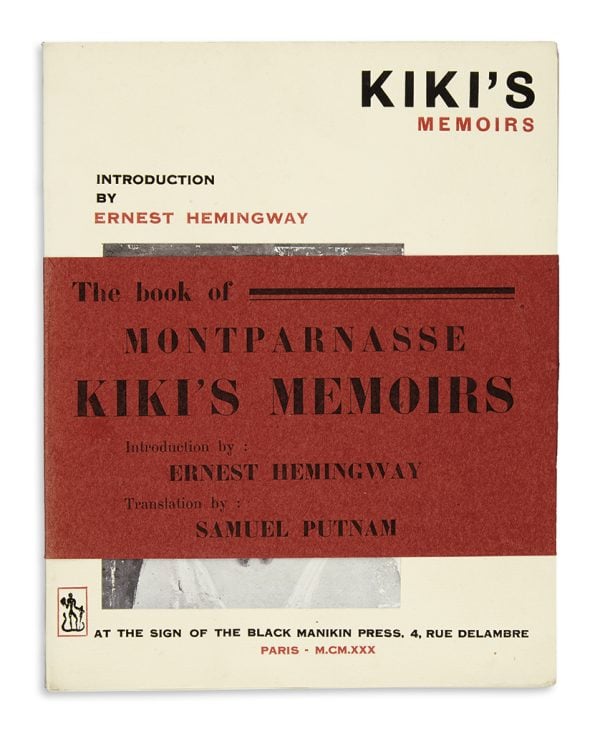

Kiki’s Memoirs by Kiki de Montparnasse, translated from the French by Samuel Putnam, and published in the U.S. by Black Manikin.

After splitting with Man Ray, De Montparnasse began dating the cartoonist Henri Broca, and paying to publish his new magazine, Paris-Montparnasse. That led in turn to the release of De Montparnasse’s memoirs, pairing her writings recounting her life with various artworks she had featured in over the years.

She was just 28 years old. She was also undeniably famous.

“Who doesn’t know Kiki, in Montparnasse, and therefore the whole world?” one reviewer asked. Another proclaimed that “Kiki is a lively girl, rowdy painter, and bohemian writer, rolled into one. She is everything.”

Bookseller Edward Titus arranged to bring a translation of the book by Samuel Putnam to the U.S. It was to have a preface by Ernest Hemingway, who wrote that De Montparnasse “dominated the era of Montparnasse more than Queen Victoria ever dominated the Victorian era.”

But for De Montparnasse, transatlantic fame was not to be. U.S. customs officials seized the first shipment of the book as obscene, and no more English language copies were printed.

A photo of Kiki de Montparnasse by Julien Mandel. Public domain.

Kiki earned the second half of her name in 1929, at a variety show hosted by Paris-Montparnasse ahead of the publication of her memoirs. She sang her most popular numbers before a packed house, paying tribute to the neighborhood’s already fading glory days.

At the end of the night, there was an over-the-top coronation ceremony, crowning her Queen of Montparnasse. Her new name, Kiki de Montparnasse, not only recognized her as artistic royalty, it inextricably tied her to the neighborhood that had birthed such inspiring and groundbreaking art. It recognized her foremost position among the artists of Montparnasse, not only as muse and model, but as an equal party to the creative process.