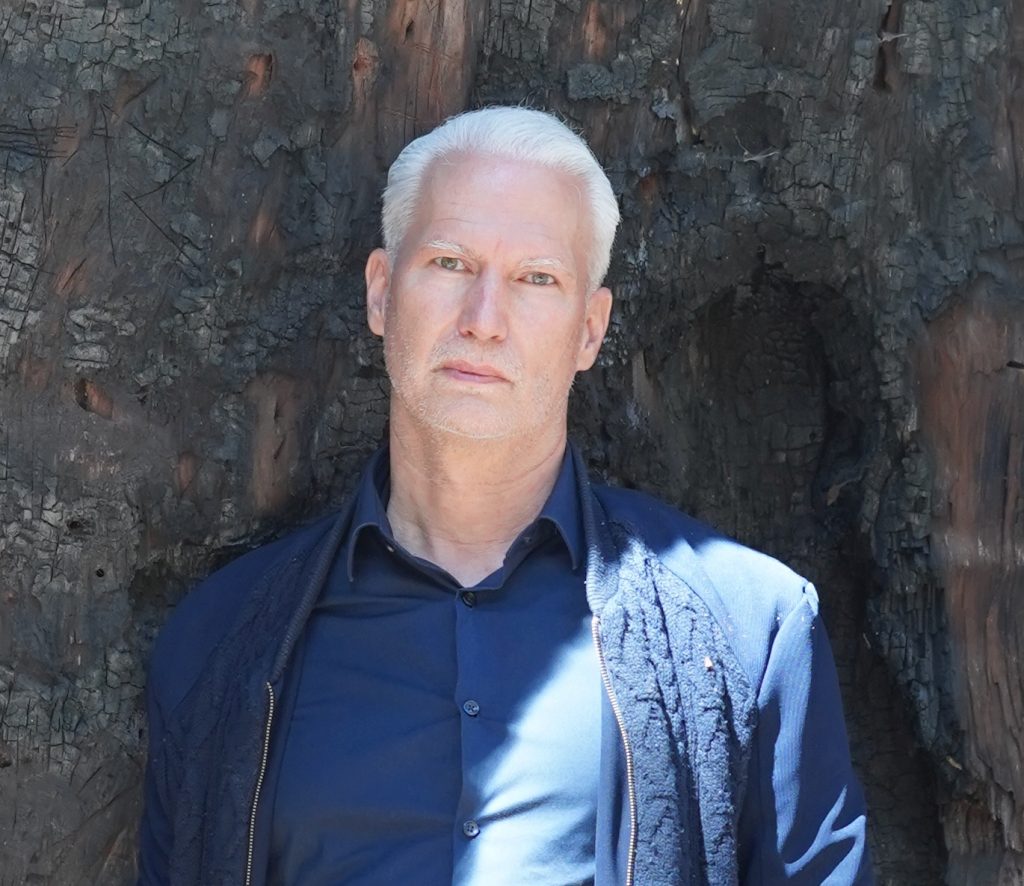

Tucked away in a corner of the Neue Nationalgalerie is the office of the Berlin museum’s director, Klaus Biesenbach. Looking onto the sculpture garden, it is just beyond a section of the museum’s permanent collection of modern art centered on reflections of war. Among the pieces on display is Otto Dix’s Die Skatspieler, a collage depicting three, card-playing veterans with grotesque and surreal interpretations of prosthetics (one player has a leg for an arm). A study on the harrowing effects of war, the 1920 work survived the world conflict that followed years later when other pieces by the artist were burned after Dix was labeled a “degenerate artist” by the Nazis.

It is among the many examples of how the collection of the Neue Nationalgalerie, part of a conglomerate of separately run institutions in the German capital known as the Berlin State Museums, holds the heart and mind of the city like no other. The traumas experienced and inflicted are interpreted here; Berlin’s cultural status is encapsulated by its Gerhard Richters and Picassos; its building is a glass and steel emblem of post-war renewal.

But it is not a complete picture, as Biesenbach, who took the helm of the museum in January, points out. For example, design, architecture, and photography—”disciplines that made the modern modern”—are largely absent. He wants to address those areas in the planned Museum of the 20th Century, which is he also overseeing. Female and Turkish artists (Berlin has a large population of individuals of Turkish descent) are woefully underrepresented. He plans to loan in-demand works—like a Dix, for example—to bring in these other voices. “I have to work internationally since I have no acquisition budget,” he says. “In America, museums are close to the art market. Here, we have a different role.”

Shirin Neshat’s 1993 work at the Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin. © Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin.

Biesenbach is the right person for this museum, in that sense, as he is an international curator with stars and powerful patrons in his contact list. He can bring in outside influences, too, presumably—loans, partnerships, and support. Currently, he is trying to convince a few choice collectors (he counts Agnes Gund, Patti Smith, and Marina Abramovic as friends) to lend out pieces for a show next year of 75 works by Isa Genzken to mark her 75th birthday. “An artist like Isa is not getting better just because a curator tries to be incredibly smart about what to do,” he notes. “She is such a strong artist that you can do a simple concept like this.”

Biesenbach’s office in the newly renovated museum reflects someone who is ritualistically on the move. Books and papers are neatly spread out around his desk, which is otherwise bare as if someone has just moved in. Art books are not yet on a shelf but instead lined up along the perimeter of the carpeted floor; there is an A4 printout of a Genzken work taped to the wall; there is not much else in the way of decorum. He has been contemplating what kind of tree to get (he gestures at a size—he wants a large one) but has not quite settled on a species.

Besides housing Berlin’s main art collection, the Neue Nationalgalerie also has historically hosted celebrated, avant-garde artistic takeovers since it opened in 1968. (This makes Genzken a natural fit.) Back in the early days, Biesenbach notes, there were more experimental projects, like happenings and even a circus. More recently, Otto Piene took over the space, just before it closed for a six-year renovation in 2015. In 2022, Barbara Kruger marked the museum’s return after an Alexander Calder show in 2021. Biesenbach sounds excited to mine its older, quirkier legacy of improvisational programming.

Musician Älice performs in the sculpture garden of the Neue Nationalgalerie as part of the “Sound in the Garden” concert series. For the first time since 1986, live concerts were held at the museum. Photo: Christophe Gateau/dpa (Photo by Christophe Gateau/picture alliance via Getty Images).

“How the museum opened is not so far from how I deal with it now,” says the German director. This summer, there was a musical performance in the sculpture gardens—the first since 1986. He also wants to have an event with singer and performance artist Solange in 2023, and the musician Arca. Politics has also inspired him to bring in a more impromptu spirit: he held a 48-hour vigil for the war in Ukraine, keeping the museum open and running an open mic along with a fundraiser (he slept in the museum). More recently, he held an event to show solidarity with protesters in Iran; both acts garnered headlines in the press.

The Museum of the 20th Century

Given its importance, the public has strong and fiery opinions about the Neue Nationalgalerie; views on the future museum next door, are just as passionate, to say the least. Due to be finished in 2026, and projected to cost €450 million ($500 million), the Museum of the 20th Century is now being called a “climate killer” and there are calls to rework the plans to ensure the massive, concrete institution is more ecologically-minded.

Biesenbach is trying, he says, to do what he can to make it socially and environmentally sustainable. Ground was broken and Herzog & de Meuron’s bid was accepted years ago, but he is in talks with members of the German parliament. The German government allocated €10 million ($10.3 million) to look into its energy issues.

“The Art of Society: 1900–45.” Exhibition view, Neue Nationalgalerie, 2021. © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Nationalgalerie / David von Becker

How much, in general, can be rerouted and changed when it comes to these massive, state-funded institutions? It is bigger than one director, certainly. In Berlin, a lot of the cultural cogs are in motion along the slow-grinding paths set by the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. The organization has been critiqued for being too expensive and too bloated to work efficiently. Germany’s last culture minister even went so far as to disband it, in parts. It is one reason why the Hamburger Bahnhof and the Neue Nationalgalerie are no longer run by the same curators.

By comparison, Biesenbach has spent the past two decades at U.S. museums, which have their own issues, but are far more nimble. So were his days in Berlin, in the 1990s, when he helped launch two of Berlin’s legacy institutions of contemporary culture. In the 1991, he founded the city’s beloved KW Institute for Contemporary Art in an old margarine factory. In 1996, he launched the Berlin Biennale.

He recalls it as a period marked by a scrappy way of working in a recently reunited art scene in Berlin. “I think it was protected by not knowing all the hurdles and challenges,” he notes. “But I should not compare the time after the Berlin Wall fell. This was, in the most beautiful sense, a very productive chaos. So many things had to be rewired and reconnected.”

Nearly 30 years later, Biesenbach does seem like a foreigner in a way. He notes that Germany is overwhelmed by a “paralyzing bureaucracy” that has increased tremendously since he left to helm MoMA PS1 and, later, MoCA LA. “Coming back, I was actually pretty shocked,” he says. “I think internationally, museums are more oriented at making things possible. What does an artist need? What is the exhibition’s goal? Then, you try to facilitate that.”

Klaus Biesenbach founded KW Institute for Contemporary Art in Berlin. Photo: Frank Sperling.

The city has changed dramatically, more than many other places. But so have museums around the world, which have been called upon to serve the public in new, meaningful ways by becoming bastions of economic, societal, and ecological change. And the pressure is on.

As I left our meeting, through the office door that led me to the gallery with Dix’s work, the guards panicked. I realized it was because I was carrying my bag and had my jacket on, both against new rules established to prevent attacks by climate activists who have been active all over Europe, gluing themselves to art and throwing substances on paintings. They escorted me out to the coat check.

What’s more, there is a sociopolitical crisis brewing. The city is experiencing a staggering rise in the cost of living. This is putting pressure on institutions, people, and businesses of all sizes. Many in the art world are anxious about being squeezed out. This has been aggravated by a looming energy crisis.

A rendering of Museum of the 20th Century in Berlin, which will be beside the Neue Nationalgalerie. © Herzog & de Meuron.

Biesenbach says that museums are a service, and should act as such. “A museum is a citizen among citizens, it is like a library or a hospital. It has a civic duty,” says Biesenbach. He has been notably trying to facilitate this in the short-term. At the opening of a show of work by Monica Bonvicini last week, he noted that the front of the museum is now a tea kitchen. One can sit on Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona chairs and serve tea or coffee out some vacuum flasks. “I would like to offer a space where people do not have to be alone,” he said. “I think people are less afraid of the cold in Europe this winter than the danger of going out. People do not want to be lonely and uninspired.”

Along a similar vein of thinking, the museum’s vigil for Ukraine collected portable chargers, money, and smartphone batteries. “Berlin ultimately is very Eastern,” notes Biesenbach, as we spoke about life in Berlin both immediately after the fall of the Wall and now. He explains: “The gas pipelines and the closeness to Ukraine, the closeness to Russia, the closeness to the Eastern European countries… I think this all becomes, all of a sudden, so much more obvious.”

Outside the Neue Nationalgalerie in September 2022 © Kulturprojekte, Photograph: Alexander Rentsch.

Artists Anne Imhof and Olafur Eliasson, two art stars of Berlin, were named as backers of the Ukraine vigil project, perhaps to bring more attention to it. That mix of celebrity power and street-level organization is very much part of Biesenbach’s curator toolkit, although this has not always pleased everyone. He is a celebrity himself on Instagram and uses social media to connect with people. He organized a one-day flash event at the Neue Nationalgalerie to draw attention to the recent anti-government protests in Iran when he found out that, by chance, Paris-based artist Shirin Neshat was in town. The Iranian artist unraveled a monumental banner at the museum and before it the museum held an afternoon of performance, readings, poetry, and speeches by Iranian artists.

Neshat, who is represented by Gladstone and Goodman galleries, is a well-known Iranian artist who was banned from the country in 1996; some take issue with her depiction of Iranian women in her work, and how centered her voice has become. In spite of this critique, the Neue Nationalgalerie was one of the only major museums to host an event—similar to the Ukraine vigil.

Berlin, on the upside, has more money flowing into culture than ever before. Almost all of the city’s institutions have new directors: Sam Bardouil and Till Fellrath took over the Hamburger Bahnhof; Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung will lead the Haus der Kulturen from January; and a seat at the Gropius Bau is available now that outgoing director Stephanie Rosenthal has signed on with the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi museum.

When asked how much he speaks with his fellow Berlin museum directors, he says that he works locally. By that, he means with his direct neighbors: the heads of the institutions around the Kulturforum, the Gemäldegalerie, and those from the Neue Nationalgalerie gather for occasional meetings in the middle zone.

“Kulturforum is a little bit like the MoMA I always dreamed of,” he notes, in reference to the interdisciplinary nature of the group of institutions. There is the Berlin philharmonic orchestra, as well as a Museum of Prints and Drawings, a library, and the museum of craft. Besides that tree in his office, Biesenbach has also been wondering how to fix the concrete expanse that extends from the Mies van der Rohe building to these places, as well as the site of the unbuilt new Museum of the 20th Century.

Ukrainian artist Maria Kulikovska lies under the Ukrainian flag for her performance “254” outside the Neue Nationalgalerie on April 27, 2022. Photo: Carsten Koall/Getty Images.

What’s to Come

Besides his happenings and events, he has not yet had a chance to kick off his own exhibition programming, so 2023 will be an important year. He is planning a Nan Goldin show (the artist has a part-time residence in Berlin, but has never had a major show here), in collaboration with Moderna Museet, Stockholm, where her work is on view now in her largest survey yet. Tehching Hsieh’s durational performances are also on the calendar.

He is also working to install a skateboard ramp next year together with the South Korean artist Koo Jeong A. The expanses of smooth concrete in front of the museum make for one of the city’s best skate spots, although last year, the practice was officially forbidden by the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation—that umbrella organization that oversees the Berlin State Museums. Biesenbach would like to “honor” the culture anyway, he says.

A colleague of his pointed out that Berlin’s missing something like the Moderna Museet and the Stedelijk in Amsterdam. “I had never thought about it this way, but it is interesting to look at Berlin from, and not find an equivalent here,” he adds. He aims to partner with both institutions, but also with platforms further afield like the Sharjah Biennale. He also wants to work with institutions in Turkey, too, given Berlin’s close ties to the country.

Members of the Berlin action alliance “fair share!” lined up around the Neue Nationalgalerie for a performance during International Women’s Day. (Photo by Paul Zinken/picture alliance via Getty Images)

He is particularly excited about an exhibition looking at Josephine Baker as both an artist and an activist. It will be a counterpart to a show at Kunsthalle Bonn also planned for next year. “Activism is not about posting things on Instagram, it is about living like Josephine Baker did—at her own risk, courageously, all her life,” he says. He sees her exhibition following the same lines as his famous show with Marina Abramovic at MoMA, which had a section called “Art is Life and Life is Art.” He notes how Abramovic and her former partner Ulay had manifested that life as a daily practice was art. “I want to apply that to Josephine Baker along a much longer time span,” he says.

He plans to show of Brazilian conceptual artist Lygia Clark, too. “In Germany, people are always talking about Joseph Beuys,” he says. “If they are going to do that, they need to know Lygia Clark. She is a giant of the 20th century.”

Between all of that, the Genzken show and the musical interludes, not to mention getting some form of the Museum of the 20th Century off the ground, he is working to get to know the space. “The museum is an instrument you have to learn to play. I think it would be wrong to have the most beautiful violin and try to play the piano.”

He will also likely continue to organize last-minute happenings that respond to whatever crisis is unfolding. “We live in a country where art immediately sets things off,” he says. “In California, the most important thing is a seismographic alarm. In Germany, the most important thing is the free expression of art. That is the basis for our democracy: Art is a seismographic indicator of whether we are going in the right direction.”

More Trending Stories:

The Class of 2022: Meet 6 Fast-Rising Artists Having Star Turns at This Year’s Art Basel Miami Beach

Scientists Discover the Existence of a Previously Unknown Roman Emperor During an Analysis of Ancient Gold Coins

Meet Sunday Nobody, the Meme Artist Who Entombed a Bag of Flamin’ Hot Cheetos in a 3,000-Pound Sarcophagus Time Capsule

The Discovery of the Oldest Human Footprints in North America Thrilled Researchers. It Turns Out They May Not Be So Old

Three Decades Ago, Klaus Biesenbach Revolutionized Berlin’s Art Scene. Now He’s Back to Steer Its Most Prestigious Museums—and He Has Big Plans

Click Here to See Our Latest Artnet Auctions, Live Now