Art World

Oops! A New Documentary About the Knoedler Fakes Scandal Accidentally Included an Artist’s Trick Image as Real

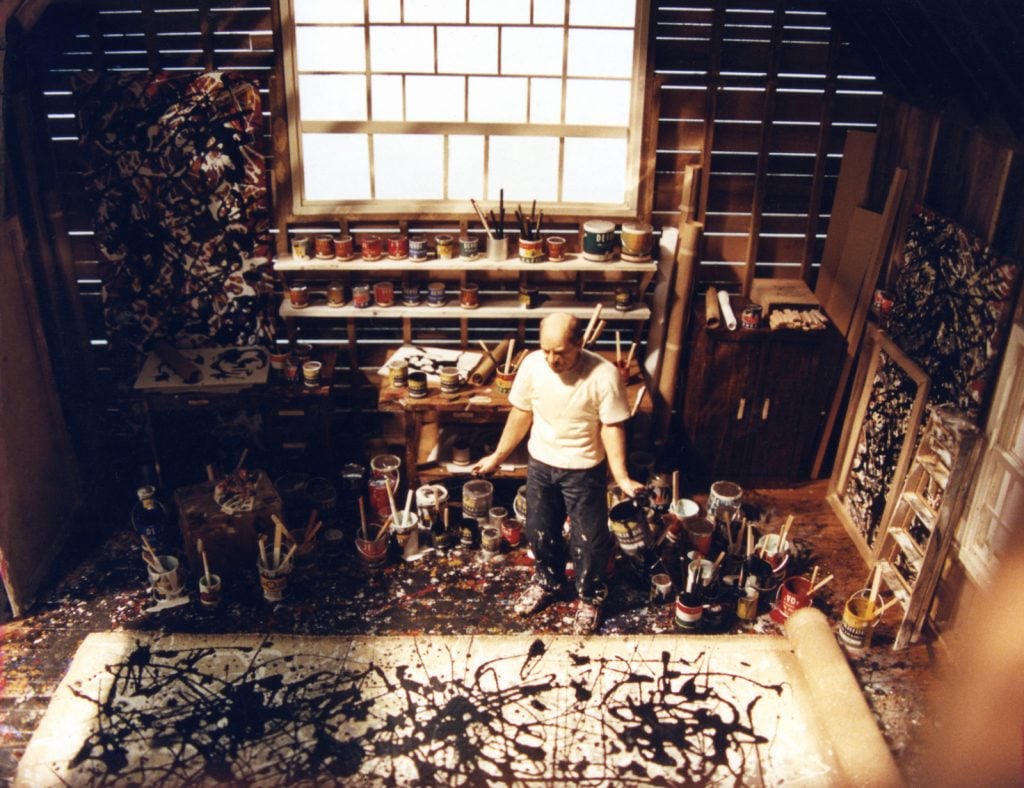

This looks like a picture of Jackson Pollock in his studio, but it isn't.

This looks like a picture of Jackson Pollock in his studio, but it isn't.

Brian Boucher

Artist Joe Fig was just looking to unwind with his wife by tuning into Netflix last weekend when he got a shock.

They settled into Made You Look: A True Story About Fake Art, an engaging documentary (Variety calls it “lively and fascinating”) that recounts the scandal of a century. New York’s Knoedler & Co. gallery had survived a Civil War and two World Wars over more than a century and a half, until an unassuming Long Island woman, Glafira Rosales, started showing up with paintings supposedly by Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko with no paperwork and a mysterious (and changing) backstory, available for way less than market rates.

The gallery’s director, Ann Freedman, sold some 60 works for a total of $80 million. When it emerged that they were painted by a Chinese immigrant, Pei Shen Qian, at his garage in Queens, the gallery shuttered practically overnight. The numerous trials that resulted held the art world in thrall.

But Fig and his wife didn’t get far into the film. About 15 minutes in, we see black-and-white photos of Motherwell and Rothko surrounded by their work, illustrating a point by Harvard University Art Museums conservator Marjorie Cohn, who says, “I mean, you would have thought that at least one of those pictures might have appeared as a background shot showing one of the artists in his studio.”

Then comes a color image of Pollock in his studio. Only it’s not an image of the artist’s studio. It’s an image of a small sculpture of Pollock in his studio, created by Fig.

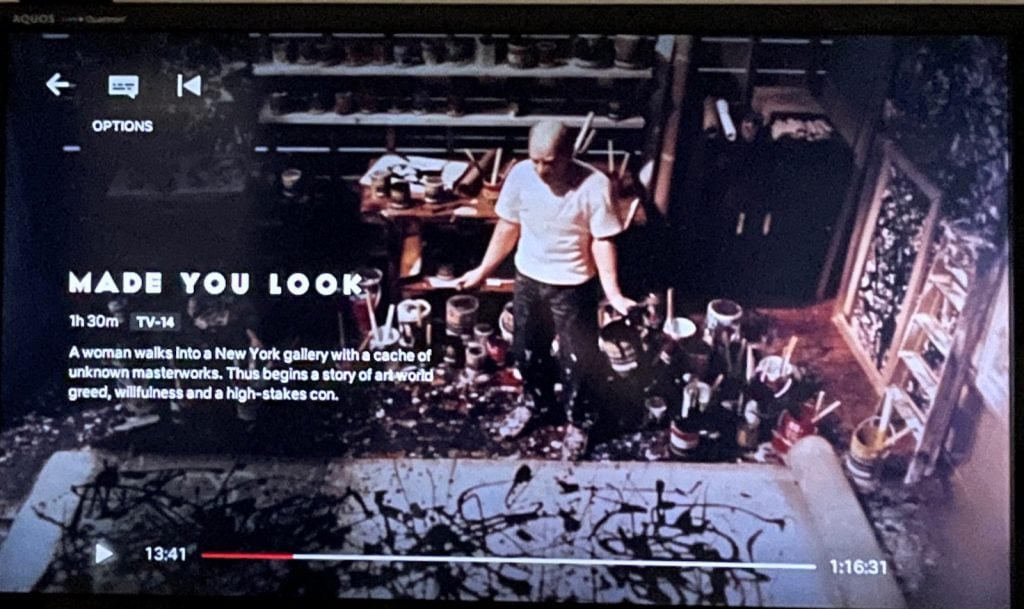

A still from Made You Look. Photo Joe Fig.

“We were literally in bed watching it,” said Fig in a phone interview. “And I was like, ‘That’s my image! What?!’”

Fig has created models of various historical artists (De Kooning, Johns, Alice Neel) in their studios as part of a long-running inquiry into the lives of creative people. (He’s also turned his eye on contemporaries like Petah Coyne, Kate Gilmore, and Ursula von Rydingsvard, and for the record, I wrote the essay for Fig’s last New York show, at Cristin Tierney Gallery.)

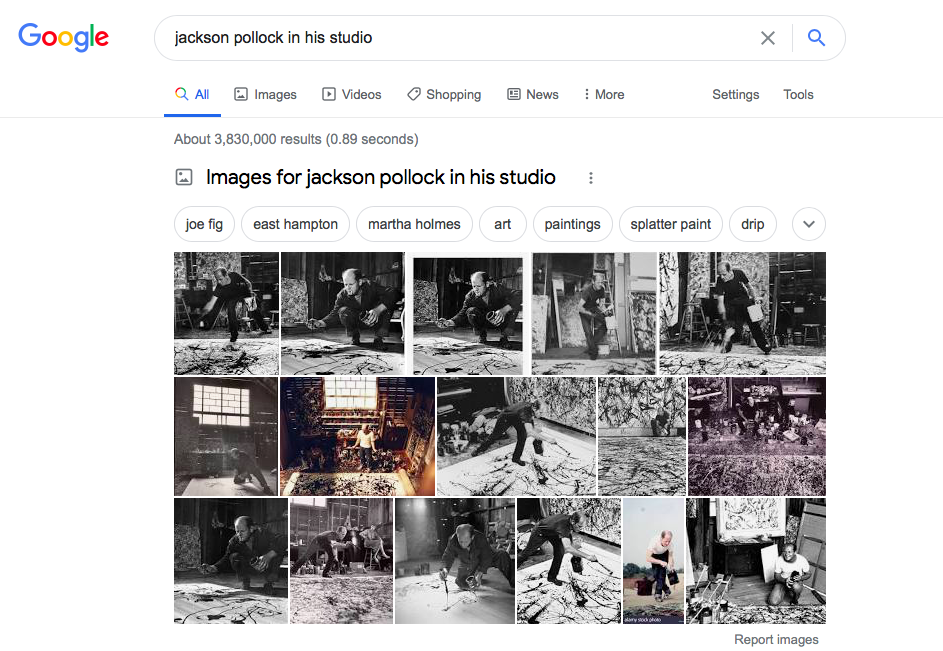

Google results.

Fig’s work has good visibility. Just Google “Jackson Pollock in his studio” and you’ll see Fig’s image, right there in the second row of results, alongside the classic Hans Namuth photos. You can imagine how a production assistant could make a mistake. Publishers and journalists have either approached him looking for more images of Pollock in his studio, or used the photo in articles. (Heck, Artnet News made the same error!)

“It was very strange,” Fig said. “A documentary about fakes, with a fake photograph?”

“Maybe at first glance, this could fool you,” he said. “But you could usually tell these things are miniature. Usually, in the photographs I make, I show the figures from the back, because when you look at the faces, it looks fake, or blurred. Some of them are pretty convincing, like Chuck Close. But they’re not meant to fool anybody.”

But they do, again and again.

Barry Avrich, the film’s director, acknowledged the mistake in an email to Artnet News, and said he and the artist had sorted things out.

Indeed, the story has a happy ending. At Tierney’s suggestion, Avrich made a donation in Fig’s name to the New York Foundation for the Arts’ pandemic response fund.