Have you ever wondered what your rights are as an artist? There’s no clear-cut textbook to consult—but we’re here to help. Katarina Feder, a vice president at Artists Rights Society, is answering questions of all sorts about what kind of control artists have—and don’t have—over their work.

Do you have a query of your own? Email [email protected] and it may get answered in an upcoming article.

I’m an artist and I’m thinking of making an NFT. Are NFTs governed by copyright? Also, what’s an NFT?

Reader, you were the 17th email about NFTs in my inbox on the day you sent this, so you know what that means: You win two tickets to a Rihanna concert at the Barclays Center! And, of course, an answer in this month’s column.

To my astonishment, NFTs (also known as non-fungible tokens) have captured the imagination of people around the world. NFTs can be made from practically anything digital—songs, Tweets, whatever. Using blockchain technology, NFTs render these infinitely reproducible items—like the song you listen to on Spotify ad infinitum—unique.

In other words, while anyone can see and easily download the video clips that constitute Grimes’ digital artwork (of which she sold a casual $5.8 million worth through Maccarone), they would have to purchase the individual, impossible-to-pirate, limited-edition NFT version if they wanted the distinction of owning the original, collectable version.

James Tarmy at Bloomberg wisely pointed out that this is essentially the same way the market for photography already functions, with an artist-made print fetching a price that is exponentially higher than a poster of the same image would. By way of comparison, I’ll remind you that a frenzy for tulips in the Dutch Republic in the 17th century at one point made the flowers more valuable than gold. The old adage is true: Scarcity really does create value.

I’ve been approached by many people interested in collaborating on NFTs because my firm, Artist Rights Society, is a clearinghouse for artist copyrights. We represent over 122,000 artists and estates worldwide, so if you want to reproduce an artwork for a catalogue or make a t-shirt for your museum gift shop, the request often flows through us. And the dynamic is the same for an NFT as it is for a t-shirt: the copyright for an artwork rests with its creator (unless the creator has been dead for 70 years).

If you’re an artist, that means you can make an NFT of your own work free and clear. If you want to make an NFT of an artwork that’s not your own, you need to go to the source for permission.

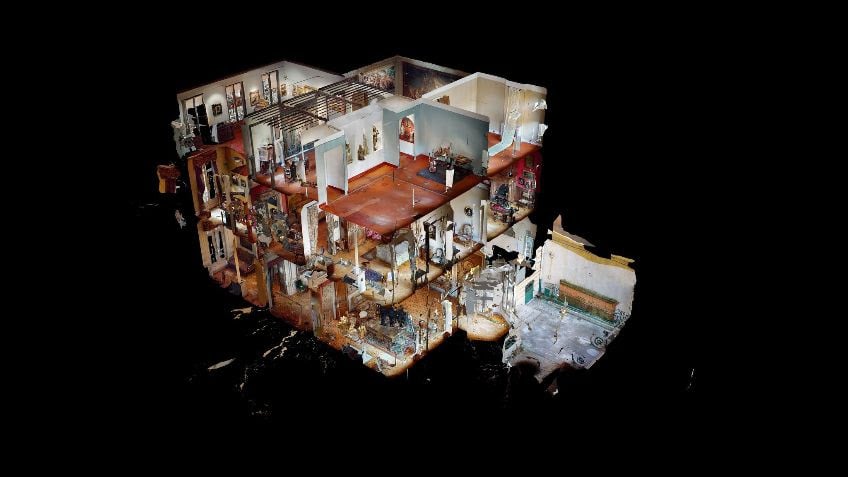

Dollhouse at Musée Grobet-Labadié Virtual Tour © Courtesy of Manifesta 13

Our museum is still closed and as we consider the long-term effects the pandemic will have on museum visitation, we would like to add more virtual components to our exhibitions, including 3D walkthroughs and extended online tours. How should we approach licensing in this situation? Should we seek permissions for reproductions in the same way we would for a print pamphlet?

First, let me thank you for your caution. We’re keenly aware that our partners in the museum world are in need of admission funds, and it’s great that you’re encouraging visitors to return at the pace that’s right for them, and for everyone else.

Museums have gotten increasingly creative in recreating their shows for viewers at home—but you’re correct to wonder about the right to reproduce content because, as readers of this column know well, ownership of an artwork rests with its creator rather than its owner. Anything you’re planning needs to be approved by the artist, their estate, or a collective rights organization like ARS.

I recommend thinking about virtual exhibitions in the same way you would think about reproducing works for print: you need to go to the same people for authorization.

The big caveat here is that copyright endures the life of the artist, plus 70 years post mortem. So if you’re a museum with many older works like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, you would already be in the clear. Best of luck with this and with your reopening.

Instagram photo Illustration by Omar Marques/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images.

How should you deal with people who share your work on Instagram but don’t tag or hashtag you (specifically, influencers who make money from the site)?

I’m sorry to hear you are having this problem. Instagram has opened many doors for many artists—but of course, nothing comes without a price. We get this query from artists time and time again.

Let’s start off by discussing your rights. Six photographers are currently suing Buzzfeed over its use of their images of this summer’s Black Lives Matter protests. But Buzzfeed’s actions may, unfortunately, be acceptable thanks to what one judge called “a non-exclusive, fully paid and royalty-free, transferable, sub-licensable, worldwide license” that is implicitly granted by posting to Instagram.

That situation sounds a bit different from your problem, however. It seems that higher-profile users are either passing off your own Instagram photos as their own or photographing your work without giving you credit.

The latter concerns your “display rights” as a copyright holder. It’s a surprisingly tricky issue because there isn’t a ton of case law established here. There are a number of questions to consider: For starters, has the person photographed your work in a way that might be considered transformative due to their own creative input? To what extent is the photograph about your work, and to what extent is it about the influencer? (If the influencer is taking up more than 50 percent of the image by, say, posing in front of your painting, the photograph may be considered more about them than about your work.) Is the image likely to hurt your market? (An argument could be made that by even unwittingly sharing your work, the influencer is boosting your profile.)

You can see how complicated this gets. For more, allow me to direct you to this lengthy article by Herrick, a law firm that often works with the art world, about photographing works for catalogues. It’s a good, if flawed, analogy.

Now for the former scenario: If the person in question is taking your Instagram posts and claiming them as their own, we’re in more of a FuckJerry situation. Even there, however, the law is unclear because it’s hard to prove the extent to which the thief benefitted from your specific piece of content. A plaintiff who tried to prove Jerry had stolen the image for a particular sponsored post dropped his case in 2019 because he was, it turned out, “almost certainly not the original creator” himself.

Regardless of the specifics, I would try reaching out to the user in question. More often than not, this is a simple misunderstanding. And in my experience, Instagram is rarely worth a lawsuit, even if you’re Kanye West.

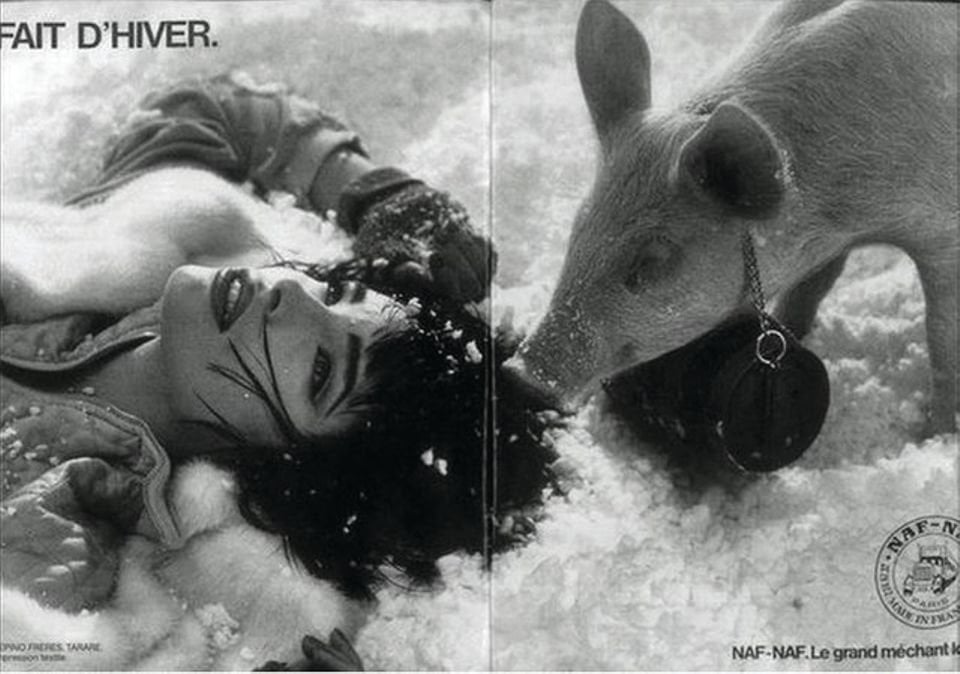

Jeff Koons’s sculpture Fait D’Hiver (1988). Photo by Ralph Orlowski/Getty Images.

Explain Jeff Koons to me. Sometimes he wins lawsuits, sometimes he doesn’t. He just lost one in France but that hardly helps to explain things. Explain Jeff Koons to me, please, somebody.

First, I’d like to put forth a personal theory that, from a creative standpoint, Jeff Koons welcomes being sued. Don’t buy it? Koons once “created” framed posters that have been made by Nike, a company well known for its rigorous lawsuits against infringements. Koons went so far as to call the works “originals,” even though they were unmodified. The guy clearly gets off on being a copyright provocateur.

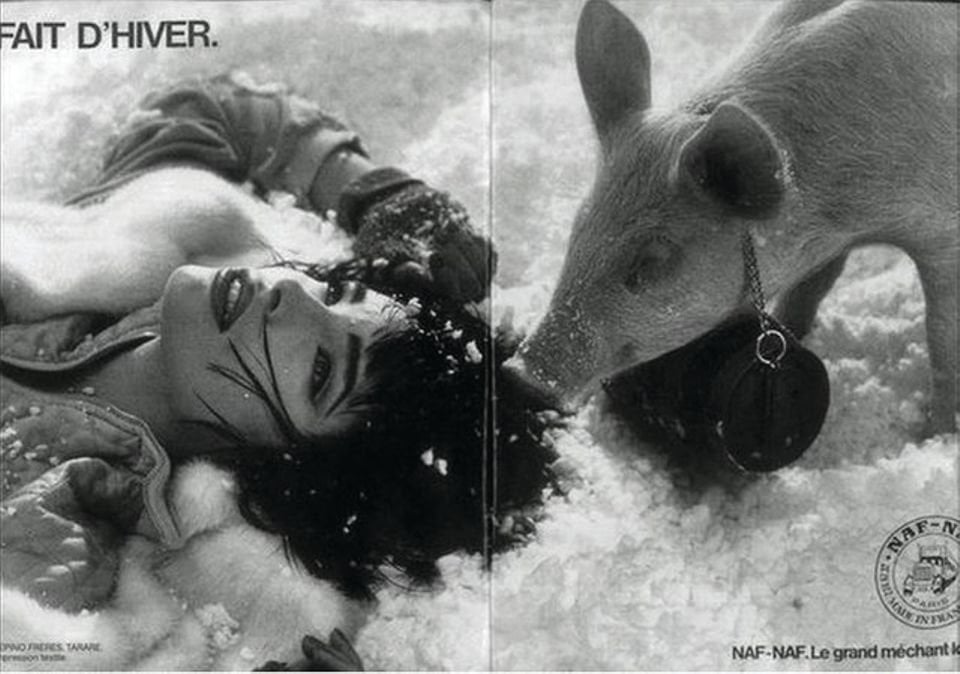

So what makes a successful Koons lawsuit? Your guess is as good as mine. The French lawsuit you cite in your question centers on Koons’s Fait d’hiver. The image is copied from a magazine advertisement, albeit a very French one, in which a pig sniffs a gorgeous woman in the snow. Sounds familiar? Consider Blanch v. Koons, which we discussed last year. In that case, Koons took a copyrighted image of a woman’s leg and feet that he found in an American issue of Allure.

Elisabeth Bonamy, Franck Davidovici, and William Klein’s “Fait d’Hiver” ad campaign for Naf Naf (1985).

The Blanch case found Koons guilt-free of copyright infringement, with the American court arguing that the original image was, curiously, too “banal” for protection. This latest suit, which occurred in France, didn’t work out for him because the laws in France tend to favor creators more than those in the States. It also couldn’t have helped that everyone’s a bit down on him over there at the moment. Mon dieu, indeed.