Have you ever wondered what your rights are as an artist? There’s no clear-cut textbook to consult—but we’re here to help. Katarina Feder, a vice president at Artists Rights Society, is answering questions of all sorts about what kind of control artists have—and don’t have—over their work.

Do you have a query of your own? Email [email protected] and it may get answered in an upcoming article.

I’m enthralled with Jenny Holzer’s new app, which allows you to recreate one of those pieces where she projects words onto buildings. (In this case, the text comes from great authors and thinkers, like W.E.B. Du Bois and Plato.) This iteration originated at the campus of the University of Chicago, but is now available around the world. My question is: How does she get the rights to all those words?

Jenny Holzer is a national treasure. In 1990, she became the first woman to represent the US at the Venice Biennale, and her work has always reflected our country’s conscience.

From 1977 to 2001, Holzer penned most of her own material, but she has said that she “quit writing because I wanted to cover more themes, more emotions, to create more depth than I could muster alone. I am not really a writer. So I began to choose texts by others.”

She is sometimes called an appropriation artist, but that term can be misleading. For one thing, her collaborators usually receive credit. (She and Polish poet Wisława Szymborska have met for pineapple, as you do.)

In fact, her clearance efforts might go above and beyond what’s strictly necessary. When you encounter Holzer’s work in the wild—say, on the back of a truck—you’re not necessarily aware that it’s an artwork, so it would be hard to argue she’s taking credit for something she hasn’t put her name on. Moreover, short phrases from longer works like books and poems tend not to be protected at all, unless they are especially distinct. (This was quickly made clear to the people who tried to make mugs that read “E.T. Phone Home” without the approval of Universal Pictures.)

Copyright also only exists for the length of a creator’s life, plus 70 years. Since this latest project involves U Chicago’s core curriculum, most of its authors are likely long gone.

So how does Holzer license these precious words, you ask? With the sort of care that we’ve come to expect from such a nuanced artist. When it comes to her own copyrights, however, Holzer has been known to be quite generous: she’s apparently never considered suing over that fake version of herself on Twitter.

A gamer plays the video game “Red Dead Redemption 2” (RDR 2) on November 5, 2018 in Paris, France. (Photo by Chesnot/Getty Images)

I’m thinking of making an art project that is a video game that could be played both in an art gallery or, if you buy one of the editions, on your home computer. The code would be based on Red Dead Redemption 2, with some dramatic tweaks to the aesthetics. Can I do this?

It sounds like you’re thinking of creating a “mod,” part of video-game hacker culture that appears to date back to 1993’s Doom (which people are actually still modding). Modding allows hackers to, for example, go into the source code, find the part that displays the bad guys, and replace them with Thomas the Tank Engine.

Mods are fun, easy, and democratic. There’s no secretly stolen code: they don’t pretend they aren’t Skyrim—they’re obviously Skyrim, just with “Macho Man” Randy Savage in lieu of dragons.

In a related matter, this past month, the Supreme Court heard arguments in a lawsuit between Oracle and Google over 11,000 lines of copyrighted code that Oracle claims Google improperly copied for its Android operating system. The settlement could be worth billions of dollars, as Oracle alleges that Google’s copying has robbed them of their deserved payday.

But unlike Google, which will undoubtedly fight this out ’til the end, you need not worry about facing a lawsuit, as your work will be sold in a very limited way to an audience that most probably does not play video games.

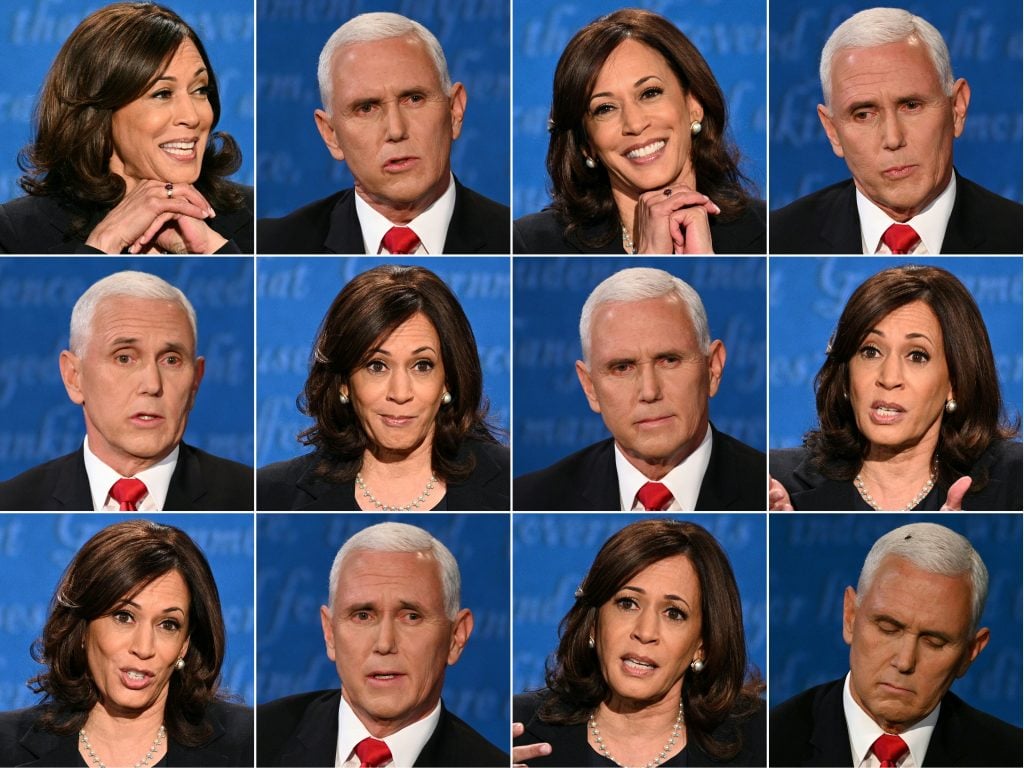

US Democratic vice presidential nominee and Senator from California Kamala Harris and US Vice President Mike Pence during the vice presidential debate at the University of Utah on October 7, 2020. (Photo by Robyn Beck, Eric Bardat/AFP via Getty Images)

Kamala Harris was extremely ? at that vice presidential debate, no? I didn’t find anything particularly compelling going with Mike Pence, though I did enjoy his opening zinger about Joe Biden’s history of borrowing language for his speeches. What’s the big deal about copying political speeches anyway? Can someone like Joe be sued?

It seems Mike Pence did manage to land at least one major blow during the debate, and indeed, in 1987, then-Senator Joe Biden did admit to borrowing language from a British politician’s speech. However, if you’re looking for political precedent for “soft plagiarism,” as I would call it, you won’t have to look very far, as this sort of thing is fairly common, and definitely bipartisan.

First Lady Melania Trump has been accused of it, as has Senator Rand Paul. President John F. Kennedy allegedly stole the iconic “ask not what your country can do for you” line from either his headmaster at Choate or Lebanese-American writer Kahlil Gibran.

Even though they all kind of sound similar (sometimes even identical…), political speeches actually carry the same copyright protection as any other piece of long-form text. Depending on how the speechwriter is employed, the copyright could be owned by either the campaign or the speechwriter. Thus, just like works of art, speeches are eligible for licensing (though this right isn’t exercised too often since people don’t tend to show up or tune in to hear an old speech).

Still, every once in a while the issue does come up: the team behind Ava DuVernay’s 2014 MLK biopic Selma had to make up a bunch of fake Martin Luther King Jr. speeches because the King family had already licensed the originals to Steven Spielberg.

So yes, political speeches on the campaign trail actually are eligible for copyright. But if you’re reading this, Mr. President, you cannot sue Saturday Night Live. After all, satire is fair use.

Grimes performing at a party hosted by Pace and Kayne Griffin Corcoran for James Turrell’s Roden Crater. ©BFA Photos: Linnea Stephan and Eunji Kim/BFA.com

I’m planning a performance that involves playing a pop song I’ve made from 87 platinum hits. (Yes, the number is deliberate.) Am I opening myself up to 87 lawsuits?

Your question takes me back to the heady days of the mid-aughts, when we would listen to Girl Talk—who, for our Gen-Z readers, is an engineer from Pennsylvania who would weave 10-second samples of the Talking Heads and Ice Cube into new songs—and Danger Mouse, who mixed the Beatles’s “White Album” with Jay-Z’s “Black Album” to give us “The Grey Album.” We once called these mash-ups.

Since then, sampling has become more mainstream, with Nicki Minaj and Kid Rock putting out songs that sample so much of the original—“Anaconda” and “All Summer Long,” respectively—that they’re essentially the same song with some new verses. This might lead you to believe that copyright laws have become looser, but that’s not the case. Almost all sampling requires clearance from the original artist, and as sampling continues to grow, so does the business around it.

Girl Talk and Danger Mouse got around this problem by distributing their works for free. But the current state of pop music, rife as it is with DJs, has turned songs into such lucrative commodities that even the Church of England has been investing in back catalogues. The stakes have been raised for everyone. Minaj is currently heading to court to defend her use of a Tracy Chapman song as the building block for a new collaboration with Nas, despite the fact that the song hasn’t even been finished yet!

Back to your original query: Since you are not sampling a single song, but rather 87 of them, that math leads me to believe you are using small snippets, not recognizable chunks of music. There is a loose precedent dating back to “Paul’s Boutique,” perhaps the first all-sample album, that borrowing up to six seconds of a song is acceptable.

Additionally, since your song will be part of a performance and therefore isn’t something you’re selling, you should be in the clear. I, for one, can’t wait for the day when I can buy a ticket and stand in that audience, mask-free, rocking out to your medley.