At first, they might appear innocuous: document-sized gray and white boxes, neatly stacked on shelves and organized by year. The Kunstverein Munich’s archive, stretching back to 1823, charts the activities of the city’s premier arts institution, but as it celebrates its 200-year anniversary, the institution’s leaders are working to prove that archives are anything but static.

Their existence is also not a given. The institution used a lot of time and effort to track down and structure the materials. “When I arrived four years ago, the archive as we know it now did not exist,” said director Maurin Dietrich. Rather, it was scattered between boxes in the attic, basement, and city archives.

And despite the Kunstverein’s two-century history—and its importance in staging the first solo European institutional exhibitions by now well-known artists, such as Liam Gillick and Andrea Fraser—none of its archives were indexed or available for the public to pick through.

Detail: Exhibition by Claude Cahun, 1998; in: “THE ARCHIVE AS…,” Kunstverein München, 2023. Photo: Maximilian Geuter.

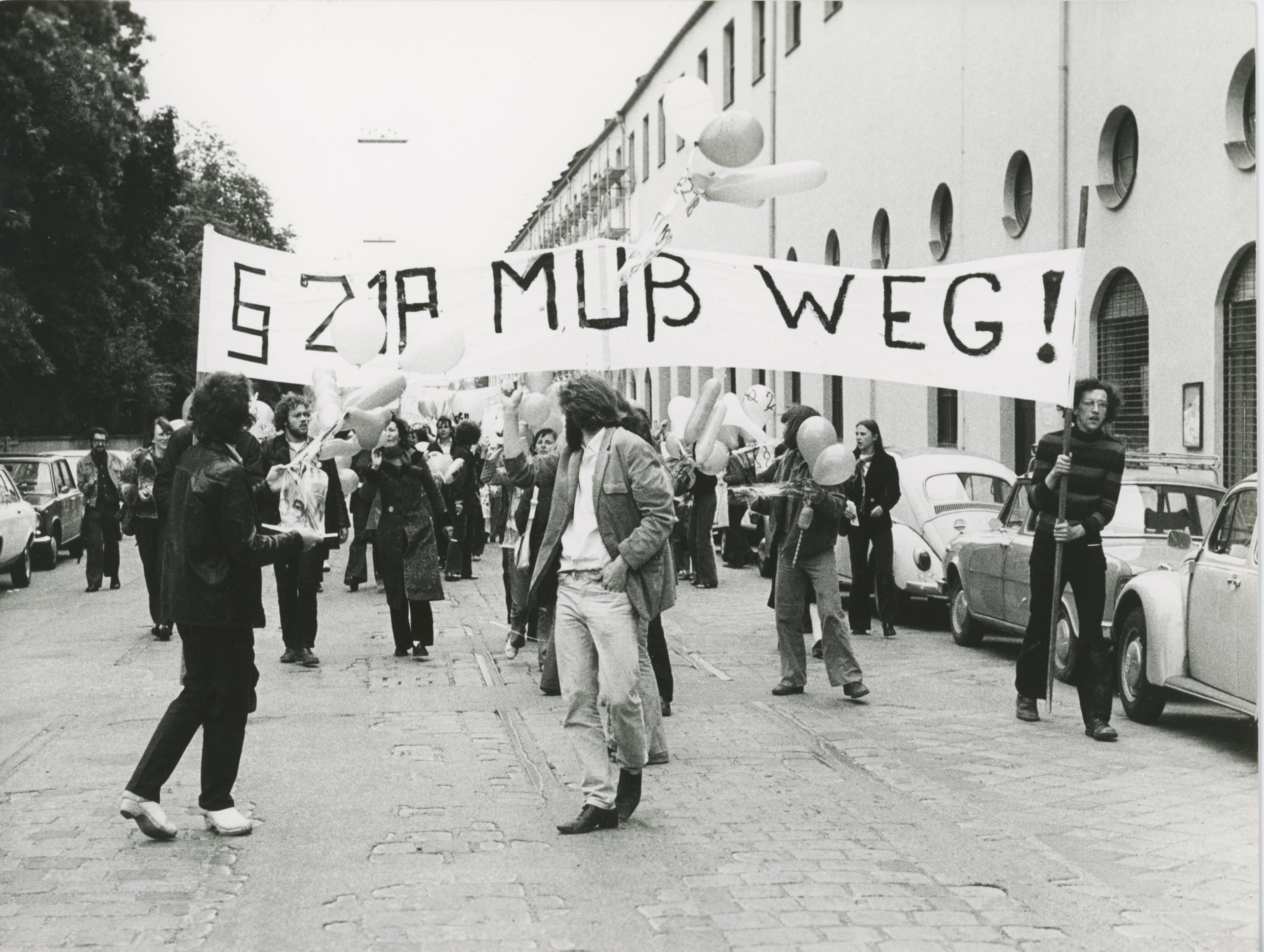

The Kunstverein Munich, with its historic arcade that runs alongside a 17th-century garden in the center of town, has a complicated history. Its past shows how cultural venues like it were complicit in the suppressive activities of the Nazi party. (Munich was the site of the Putsch that saw Hitler begin to get a grip on power, and the Kunstverein was the exhibition venue for the infamous “Degenerate art” exhibition.) At the same time, years later, the Kunstverein was also a space for civic action during the struggle for women’s rights.

After the war, Munich was where the deadly 1972 Olympics took place. It is also where, last summer, Tony Cokes’s poignant show “Some Munich Moments” appeared, which delved into the archives and visual language used around the 1972 Olympic games. The curatorial team has also brought together critically lauded solo presentations of U.S. artists Pippa Garner and Diamond Stingily, among others.

Curatorial team of Kunstverein München from left to right: curator Gloria Hasnay, assistant curator Gina Merz and director Maurin Dietrich, 2023. Photo: Manuel Nieberle.

Its project of late is emotional for the city. The anniversary event was celebrated last weekend with talks, music, dancing, and an impossibly long dinner table that hosted 200 guests, including former directors, curators, artists, and writers. An intergenerational public street party closed out the weekend.

Inside the venue, the institution brought its archive into the center as a malleable installation. On view until August are pieces of archival material, images, posters standing on modular shelves at the center of the exhibition space, like an open book. Put another way, there are puzzle pieces to a history, but they do not neatly fit together—nor do they need to. The transformable show, titled “The Archive As…”, asks participants to finish the phrase. It also allows the archive arrangement to be altered. (“The Archive as a Headache” is one such example, and artist Joshua Leon interjected with poignant lines of questioning in the form of notes left around the installation.)

But history and memory, and the archives, even when they’re organized, do not generate a straight line across two centuries, nor conjure easy answers. What has emerged is a story about German society, the end days of royalty, the dark period between 1930s and ’40s, the riotous 1960s and ’70s, and the contemporaneity from the 1990s to today. It also tells the story of what, exactly, a Kunstverein is—and what it might be able to become.

Exterior view of the Kunstverein Munich. Meeting of the institution’s Summer School for “The Stories We Tell Ourselves.” Courtesy Kunstverein Munich.

The Kunstverein Model

To start, some definitions. The verein model (kunstverein translates to art association) has a long history, one that is a given to most in Germany, but deserves a bit of picking apart for those based elsewhere.

There are more than half a million vereine—associations of different kinds—in the country, and they run the gamut in concept and scale. There are sports associations that are large and nationally recognized and ones that are extremely niche (it only takes seven individuals to form such an association, and one can form a verein for just about anything so long as it is legal—and, trust me, people do).

When it comes to art associations, there are around 300 dotting the nation in major cities and towns. One of its distinguishing factors from art spaces in other countries is its members. Each Kunstverein is made up of a directorship, which is voted in by a board, which is in turn voted in by a paying membership—which usually consists of hundreds to thousands of people for each institution. The body of the membership tends to outlive the board and directors, who tend to switch over at least once a decade—as such, one could say, like an electorate, forms the core of the association. In Munich, there are around 1,900 such individuals.

Liam Gillick, Three Perspectives and a Short Scenario* Work (1988–2008) Mirrored Image: A ‘Volvo’ bar, on view November 2008. Courtesy Kunstverein Munich

“It is very democratic,” said Dietrich. “Membership is an active engagement instrument that goes beyond signing a guestbook.” Member fees give it an arm’s length from political bodies, though they do rely on state funding as well. Smaller than museums, these institutions are also able to be reactive, and as such they tend to become incubators for artists who later grow to international acclaim. “The autonomy we have gives a massive space, artistically and curatorially, to experiment. Kunstvereins can react flexibly and quickly in a rather non-bureaucratic way,” noted Dietrich. “It is quite a resilient structure.”

At the Kunstverein in Munich, Adrian Piper, Martin Kippenberger, Pierre Huygue, and Philippe Parreno were among those artists who had their first major German or European exhibitions in its hall.

Given the upside, the model has been attempted in other cities, too. KW Institute for Contemporary Art’s director Krist Gruijthuijsen founded the Kunstverein Amsterdam, which then spawned a network in other cities that have remained more or less active: Kunstverein Toronto hosts programs occasionally; then there’s Kunstverein in Milan; Kunstverein Aughrim in Ireland; and New York’s Kunstverein, which wrapped up activities in 2014.

Michaela Melian (right) and Maurin Dietrich (center) during “The Archive As.. Lost in Munich.” Courtesy Kunstverein Munich.

Naturally, such a model comes with a few vulnerabilities, and this was a topic of deep discussion over the bicentennial celebration weekend, during a sprawling panel with 15 previous directors of the institution. In smaller towns, Kunstvereins can be less reliant on wider pools of paying, voting members. There is also the risk of alienating a traditional membership through ambitious or conceptual artistic programming.

But on the whole, it functions well. “What this structure does, is it creates a space where an audience is not a fiction,” said Dietrich. The members are involved, engaged, and sometimes agitating, and they may take an active role in negotiations. Dietrich suggested this is a more sustainable way to actively work with local publics. “Everyone has been talking about nurturing community,” she noted. “What does this mean if the majority of audiences and ticket sales at large museums are often one-time visitors?”

Installation view of “THE ARCHIVE AS…,” Kunstverein Munich, 2023. Photo: Maximilian Geuter.

Unboxing an Archive

As a key preamble, Dietrich and her team also hired a full-time archivist to manage the documents to help the staff, artists, and the public encounter them. While working in those archives in preparation for her solo exhibition at Kunstverein Munich in 2021, artist Bea Schlingelhoff uncovered an unsettling document: a 1936 paper detailing the barring of membership to “non-Aryans” at the Kunstverein Munich. And while there are plaques and memorials reckoning with Nazi history in Munich, Schlingelhoff questioned why there was none at this institution.

That document she had found dated to one year before the infamous the “Degenerate Art” exhibition took place in 1937 at the arts space, bringing together artists who were not approved by the Nazi state. These included Jews, Communists, and other individuals and groups deemed un-German. As part of her work, Schlingelhoff created small brass memorials for four women who were in this exhibition; their names are enshrined now outside the venue’s front doors.

Schlingelhoff’s adjacent exhibition, “No River to Cross,” which was curated by Kunstverein Munich’s curator Gloria Hasnay, received much acclaim in Germany for its poignant creation of an unsettling shadow space. Inside the exhibition venue, green rectangles all around the wall appeared like the ghostly salon painting show, calling attention to absence. The empty rectangles represent 650 works seized by the Nazis and shown in that “Degenerate Art Show.”

Bea Schlingelhoff, No River to Cross, Mapping, 2021, installation view, Kunstverein Munich. Courtesy: the artist and Kunstverein Munich. Photo: Constanza Meléndez

This show was an important exhibition that once could say prequeled the flurry of events this year. “If nothing else, the path to historical oblivion is paved by the fact that a document from 1939 sits just the same as one from 2017, or that there are predefined boxes that make everything look the same, neutral, and objective,” said assistant curator Gina Merz said of the project in a recent interview with PW Magazine.

“It seems to me that a central part of the archive exhibition is to activate the archive to raise questions of its logic and to think about the reproduction of violent structures,” noted curator Gloria Hasnay.

To correct these is to first bring them into the light—and solve for gaps and omissions. Like the whited-out name of Rachel Salamander from the board list from 2003. Salamander had stepped back and removed her name from all content in the Kunstverein to protest an exhibition that she felt was trying to recontextualize the grandiosity of Nazi design as something separate from fascism.

Salamander has since joined as a participant in “The Archive As…”, and is advocating that everyone be implicated in this kind of advocacy, research, and thinking.

“She notes that looking into histories should not be a specialized tasks reserved for historians,” said Dietrich. “Everyone who participates in social life has a responsibility.”

Friedrich Thiersch’s Perspective section of the reconstruction project for the Kunstverein building in Munich, May 1890. Courtesy Architekturmuseum der TU Munich.

There are many bright spots from its past that are being recentered, too. A few anecdotes include reflecting on the free childcare that was provided during a protest against abortion in the 1970s. The team tracked down the photographer who had documented women-led protests that took place on Kunstvereins front steps—it turned out to be Barbara Gross, who later became a noted Munich dealer. When the conservative Christian Social Union closed the academy, the Kunstverein Munich offered up its spaces to unhoused artists.

This archival material and the process that unearthed it is perhaps even more paramount to its understanding of itself than it might be for a museum. Kunstvereins are ultimately art spaces and non-art collecting entities. But what these institutions do collect is something less tangible—the time stamps of social and cultural moments that may otherwise prove totally ephemeral.

“The question is what constitutes a collection when there are no artworks [being acquired]. A Kunstverein collects the stories around the artworks that were produced, and it collects stories about the Kunstverein’s existence, which is usually very much focused on the contemporary. What [Kunstvereins] have may not constitute a collection, but what it does have, it is of massive public interest.”

“Kunstvereins think about the future, but not always the past,” added Dietrich. “This is changing right now.”

More Trending Stories: