Art History

A Dollhouse Hung With Original Art, Including a Tiny Duchamp, Is One of the Art World’s Best-Kept Secrets. Here’s Why

We take a closer look at the Stettheimer Dollhouse, one of its most beloved objects.

Update—October 22, 2024: The Stettheimer Dollhouse will return to public view at the Museum of the City of New York on November 22. Following five months of extensive conservation work, issues like dust buildup, flaking paint, and failing adhesives have been addressed. The nursery’s wall collages required special attention. The restoration also included cleaning the dollhouse’s artworks, enhancing the lighting, and installing a new display case. Dolls made in the 1970s by curator John Darcy Noble, modeled after 1920s figures like Gertrude Stein, will now be displayed separately from the dollhouse to align with contemporary curatorial practices.

This year marks the 100th birthday of the Museum of the City of New York, a museum dedicated to the history of this storied metropolis and the people who’ve inhabited it. Looking back at the museum’s storied hundred-year history, one can uncover a bevy of idiosyncratic “only in New York” stories.

For instance, in December of 1945, the Museum of the City of New York (MCNY) hosted a lavish housewarming party for a dollhouse, attended by the likes of Georgia O’Keeffe. But this unusual fête wasn’t to honor just any old dollhouse, but rather an intricate and elaborately adorned mansion, in miniature, created by Carrie Stettheimer, one of the city’s three famed Stettheimer sisters.

Miss Carrie Stettheimer, portrait photograph, 1932. Courtesy of Getty Images.

The wealthy family, German Jews in origin, were well-known amid intellectual circles and lived between New York and Europe; atypically for the time the family with five children was led by Rosetta, their mother, as their father abandoned the family and fled to Australia. The children were known to be precociously creative. An aspiring theatrical designer, Carrie was sister to Florine, the accomplished painter, and Ettie, a novelist and philosopher. The eldest of the sisters, Carrie, hosted fashionable salons alongside Rosetta, and worked on her dollhouse. Ultimately, following Carrie’s death in 1944, Ettie donated the well-adorned dollhouse to MCNY in 1945 writing, “I feel certain that no repository would have been more satisfactory to her than the museum of her own city.”

Carrie Stettheimer’s Dollhouse (1916–35). Photo: Brad Farwell. Collection of the Museum of the City of New York.

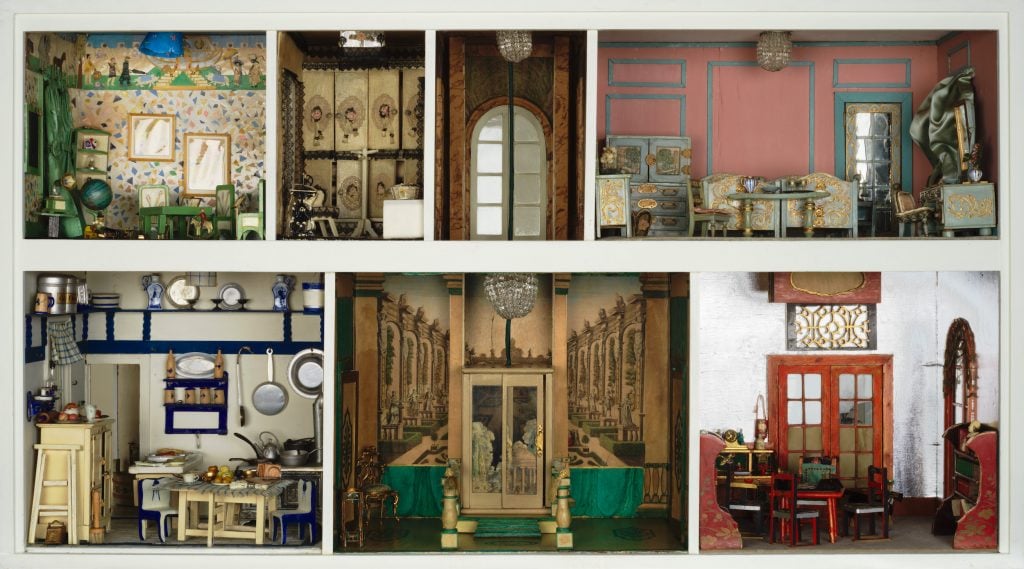

The Stettheimer Dollhouse is a two-stories measuring 28 inches tall and boasting 12 rooms, including a ballroom with a powder blue piano, an elevator, a bathroom, a nursery, a kitchen stocked with pots and pans. It is a dizzying display of detail that offers more and more to discover for those with patient eyes. One of the star collection objects of the MCNY, the dollhouse is typically on permanent view (in the fall of 2020, the museum opened “Up Close” an exhibition focused on the details of the house with visual blowouts and elucidating wall texts). Currently, however, the beloved object is undergoing routine restoration to be back on view sometime in 2024. To mark the museum’s centennial, we decided to take a closer look at the utterly wonderful Stettheimer Dollhouse and find three fun facts you might not have expected. Be sure to catch it when it’s back on view!

Stettheimer Worked on the Dollhouse for 20 Years—But Never Finished It

Carrie Walter Stettheimer, Dollhouse (1920). Gift of Miss Ettie Stettheimer, 1945. Collection of the Museum of the City of New York, 1945.125. Photo by David Lurvey/the Museum of the City of New York.

While the careers of her sisters flourished, the eldest sister Carrie Stettheimer’s professional ambitions took a backseat to her duties running the Stettheimer household at their home on West 58th Street, known as Alwyn Court. While Carrie dreamed of creating large-scale theatrical design, in its place she turned to stage sets in miniature.

Carrie made her first dollhouse, it was said, as a child vacationing at chic Saranac Lake in the Adirondacks. She solicited wooden boxes from the local grocer to construct her small edifice, a project that she donated to a local polio fundraiser held that summer. But that was only the beginning of her curiosity it seemed and in 1916, Carrie began assembling the Stettheimer Dollhouse, her magnum opus in minor scale, This lavishly detailed dollhouse she modeled on André Brook, the family’s Tarrytown estate, north of the city.

Carrie Walter Stettheimer, Dollhouse (1920). Gift of Miss Ettie Stettheimer, 1945. Collection of the Museum of the City of New York, 1945.125. Photo by David Lurvey/the Museum of the City of New York.

The new dollhouse became a never-ending project for Stettheimer who went so far as to rent a secondary New York apartment at the Dorset Hotel in order to devote herself exclusively to the task. The decor of the design spared no detail, reflecting the decor of the family’s Manhattan home; Stettheimer crafed Empire wallpaper, Limoges vases, Louis XV furniture, pots, pans, and everything else seemingly imaginable. A painting of Noah’s ark in a nursery shows the three sisters, with their pets on leashes, waiting to board the ark itself. Though now lost, the home once included little plaster maquettes of guests visiting the home. The whimsical furnishings for the home would have been “incredibly chic” in the 1920s, the MCNY noted.

Carrie Stettheimer’s Dollhouse (1916–35). Photo: Brad Farwell. Collection of the Museum of the City of New York.

But the completion of the dollhouse came to an abrupt halt when Stettheimers’ mother, Rosetta, died in 1935, and Carrie, in a decision ripe for psychoanalysis, abandoned working on the dollhouse entirely and the dollhouse was sealed in storage where it would languish for the 10 years preceding Carrie’s own death. When Ettie overtook her sister’s estate, she retrieved the dollhouse and attempted to decorate the remaining rooms in a manner she believed her sister would have enjoyed. Ettie donated the dollhouse along with a doll belonging to Carrie and an accompanying Saratoga trunk and trousseau. Considering the 19 years Carrie worked on the house, Ettie reflected upon her sister’s project with a sense of disappointment, writing “I look upon this production of Carrie’s as a facile and more or less posthumous substitute for the work she was eminently fitted to adopt as a vocation, had circumstances been favorable—stage design.” Given the dollhouse’s warm reception over the past 75 years, however, Ettie might have viewed the one-of-a-kind object more generously in hindsight.

A Miniature Art Gallery Holds Real Works by Marcel Duchamp, George Bellows, and Other Famous Artists

Carrie Walter Stettheimer, Dollhouse (1920). Collection of the Museum of the City of New York, 1945.125. 1a. M arcel Duchamp Nude Descending a Staircase, c. 1925 © Association Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2024. Albert Gleizes, Title unknown [Seated Figure], c. 1918. Bermuda Landscape [View with Palm], c. 1918 © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo by David Lurvey/ the Museum of the City of New York.

The Stettheimer household was a favorite of the art world denizens throughout the early decades of the 1900s; frequent visitors included Marcel Duchamp, photographer Carl Van Vechten, Georgia O’Keeffe, Alfred Stieglitz, and Tristan Tzara, among others. In making her dollhouse, Stettheimer solicited artists in their milieu to recreate their works in miniature. If one looks closely, they’ll notice the dollhouse is a veritable 20th-century museum, filled with works by Marguerite Zorach, William Zorach, Alexander Archipenko, Albert Gleizes, and George Bellows, among many others.

Certainly, the most famous of the works displayed in the home is Marcel Duchamp’s reprisal of his iconic Nude Descending a Staircase (1913)—this 1918 version an ink-and-wash version measures at just three-and-a-half-inches. Undeniably delightful, these teensy works can be spied in keyhole through the home’s exterior arched windows. Other crowd favorites from the collection include Gaston Lachaise’s diminutive Venus sculpture in the home’s courtyard. In fact, there are more artworks intended for the dollhouse than can reasonably fit. Over the decades, however, Carrie commissioned some 28 known works which she never managed to hang. Upon Carrie’s death, Ettie made a selection of 13 works to put on display in the home, though still others exist; it is believed they may have been intended to be displayed in their rotation.

Some of These Petite Paintings Are Still Being Identified

Louis Bouché (1896–1969). Mama’s Boy, c. 1920. Gift of the estate of Jane Bouché. Woodstock Artists Association & Museum.

While many of the paintings and sculptures made for the Stettheimer Dollhouse have well-known references, still others have yet to be identified by the museum curators. In 2016, curator Bruce Weber made an exciting discovery in this vein. While attending an exhibition at the Woodstock Artists Association and Museum in Woodstock, New York, he recognized a painting in the show as one of the yet unidentified works in the Stettheimer Dollhouse. The painting was American artist Louis Bouché’s oil painting Mama’s Boy.

Carrie Walter Stettheimer, Dollhouse (1920). Collection of the Museum of the City of New York, 1945.125. 1a. Marcel Duchamp Nude Descending a Staircase, c. 1925 © Association Marcel Duchamp / ADAGP, Paris / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 2024. Albert Gleizes, Title unknown [Seated Figure], c. 1918. Bermuda Landscape [View with Palm], c. 1918 © 2024 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo by David Lurvey/ the Museum of the City of New York.