On View

Both Reviled and Revered, La Malinche Has Been Called the Mother of Mexico. A New Exhibition Explores Her Evolving Image

A statement show, “Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche” is on view at the Denver Art Museum.

A statement show, “Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche” is on view at the Denver Art Museum.

Taylor Dafoe

Temptress and turncoat. Mother of a new nation. Chicana heroine.

La Malinche has lived many lives in the cultural imagination since her death in the 16th century, as generations of people have appropriated her image to promote their own political agendas. Now, a landmark exhibition at the Denver Art Museum (DAM) explores the complex legacy of the woman and her impact on artistic culture on either side of the U.S.-Mexico border—the first major scholarly presentation to do so.

An enslaved Nahua woman who became Hernán Cortés’s interpreter and consort during his conquest of the Aztec Empire, La Malinche proved to be a key actor in one of the defining moments of world history. Whether she did so willingly or not, we don’t know. In fact, there’s much we don’t know about her life. And yet, for five hundred years, La Malinche has loomed large in modern Mexican legend.

That much is evidenced by the 68 artworks that make up “Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche,” on view at DAM through May 8, 2022. (Following its presentation at DAM, the exhibition will travel to the Albuquerque Museum and the San Antonio Museum of Art). It’s an important presentation that doubles as a statement unto itself.

Antonio Ruiz, La Malinche (El Sueño de la Malinche) (1939). Photo: Jesús Sánchez Uribe.

The show took six years to pull together, with independent curator Terezita Romo working along with Victoria I. Lyall, DAM’s curator of Art of the Ancient Americas, and Matthew H. Robb, chief curator at the UCLA’s Fowler Museum.

“This is the first time there’s ever been an exhibition like this,” explained Romo. “Even in Mexico, La Malinche’s story is always connected to Cortés—it’s always about the conquest. This exhibition really pushes that out. It’s more about this young indigenous teenager and what she did in terms, not only surviving, but of actually changing history.”

The show is broken down into five sections, each devoted to a different personification of La Malinche’s legacy. The first, “La Lengua” (or “The Interpreter”), examines her role as an interlocutor between the Aztec and Spanish peoples, from Cortés’s first written description of her as “la lengua que yo tengo” (“my tongue”)—an appellative he used instead of acknowledging her name—to posthumous depictions of her as a woman empowered by language.

Next comes “La Indígena” (“The Indigenous Woman”), which looks at how the racial designations imposed upon her by conquistadors forms the foundation of her mythology, an otherized object of beauty from a defeated people; and “La Madre de Mestizaje” (“The Mother of a Mixed Race”), an exploration of how, in the wake of the Mexican revolution, the country adopted La Malinche, the mother of Cortés first son, as as a symbol of a new mixed race.

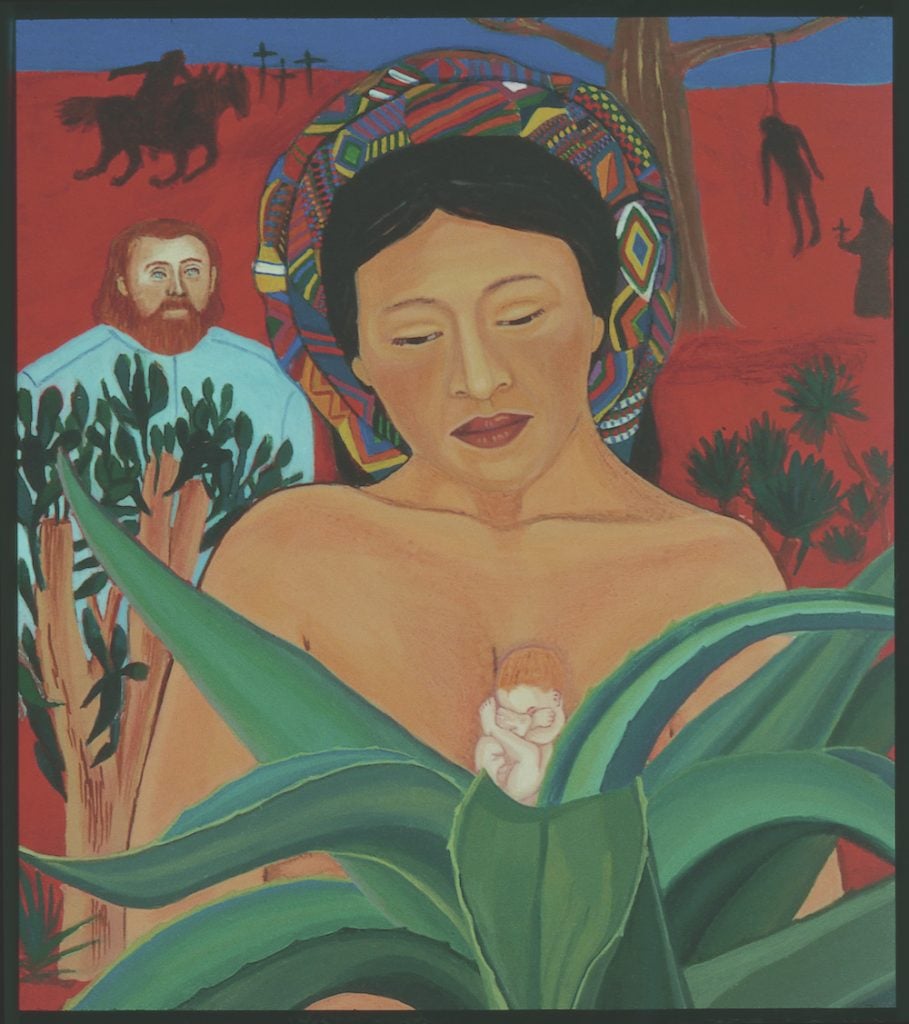

Santa Barraza, La Malinche (1991). © Santa Barraza. Courtesy of the Denver Art Museum.

By far the biggest section of the show, “La Traidora” (“The Traitor”), focuses on the way La Malinche was depicted throughout much of the 20th century—as a person who turned her back on her people, inviting generations of ethnic cleansing. (Roma points out that the most prominent examples of this depiction “mainly came from men, which is not a coincidence.”) It was during this time that the word “malinchista” was popularized as a pejorative term for someone who prefers foreign cultures to their own. Even today, it’s through that word that most Mexicans know La Malinche at all.

“One of the things we wanted to accomplish with the retelling of this story was to have those visitors who are familiar with her story reexamine their preconceived notions and to really understand how pernicious some of those metaphors can be,” said Lyall. “That her name is the basis of a slur that’s quite popular—this is a way of passively emphasizing the sexist and misogynistic view of a woman’s influence.”

In response to this period of denigration, La Malinche was reclaimed as an icon of the Chicana movements of the 1960s and ‘70s. This is the subject of the fifth and last part of the show, a section that extends to today, looking at how her image has been embraced by a number of different communities, from feminists to trans activists.

Jesús Helguera, La Malinche (1941). © Calendarios Landin.

Despite the myriad ways in which La Malinche’s mythology has been exploited, she’s always resisted reduction, explained Romo.

“That has always been the core of what has interested me about her—she was such a complex being,” the curator said. “It’s what makes her so powerful: she elicits these different representations from people.”

Thanks to their work, more people will be bringing their own contemporary interpretations to her story. Prior to the opening of the show, DAM launched a series of outreach programs, trying to both gauge the perception of La Malinche in the community and educate people about her story.

“The best comment we had was, ‘How come there isn’t a Disney princess movie about her?'” Lyall recalled, laughing. “That was definitely not the avenue we wanted to go, but to me it really underlined how, even if our visitors don’t know who La Malinche is, once they hear her story, they are hooked.”

Jorge González Camarena, Lapareja (The couple) (1964). © Fundación Cultural Jorge González Camarena, AC. Courtesy of the Denver Art Museum.

“Traitor, Survivor, Icon: The Legacy of La Malinche,” is on view at the Denver Art Museum now through May 8, 2022. It will travel to the Albuquerque Museum from June 11–September 4, 2022, and the San Antonio Museum of Art from October 14, 2022–January 08, 2023.