Art World

How Artist Ioana Manolache Transforms Mass-Produced Romanian Flags Into Inspired Works of Art

We caught up with the Brooklyn-based artist to discuss her creative process, and what it takes to complete her detailed paintings.

We caught up with the Brooklyn-based artist to discuss her creative process, and what it takes to complete her detailed paintings.

Caroline Goldstein

The Brooklyn-based artist Ioana Manolache grew up in Babadag, Romania, a tiny village where her father was a minister. From an early age, she was drawn to the images that lined her church’s walls, paintings that seemed to stare down at her from their holy perches. Along with other children, she learned how to paint in the manner of Orthodox icons, but always felt as if the attention was misplaced, and that the portraits of religious figures were of secondary importance.

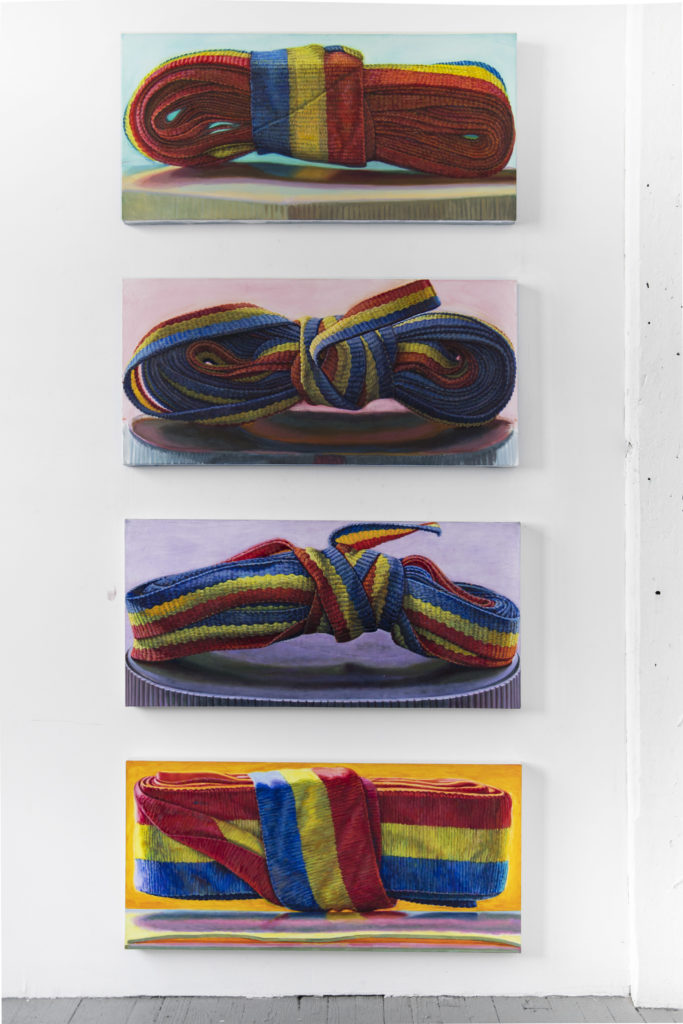

Years later, Manolache is pursuing a career as an artist, having completed college and graduate studies in fine arts in New York. We caught up with the Brooklyn-based painter about her current series, “Mother’s Knots,” to discuss the evolution of her practice, her interest in objects and iconography, and just what it takes to complete these intricate, highly personal works of art.

How did you begin this series?

My current body of work—”Mother’s Knots”—began when I asked my mother to bring me a flag from Romania, where she was going to visit for the first time in 16 years. She ended up coming back with even, all small flags, low quality—obviously mass produced to imitate a fine silk or satin, and meant to appear precious.

What attracted me to them were the details, physical moments that complicated the idealized symbol the object was meant to represent—the red thread used at the seams that puckered and warped the surface, or the plastic wrapping the flags were packaged in.

Artist Ioana Manolache. Photo: © 2019 Gregory Gentert. Courtesy of the artist.

Do you prepare for the paintings in any way? How much stock do you put in translating your original idea into the finished product?

I usually make one sketch on loose canvas paper to help capture the key formal elements—the shape, color, and general composition—which I keep on my studio wall for the duration of the painting. The sketch helps me remember the essentials, from the initial moment that sparked my interest. It’s usually a very quick and loose drawing, something that captures my first impulsive attraction. On a grand scale, the final paintings end up pretty similar to that original idea, but there are a lot of nuances that evolve over the course of the painting process. Everything is casually arranged to allow for changes of light, or accidents that might enter the work, making the object, and the painting more activated and alive.

I bring the object—in this case the (ribbon) flags—into the studio and let it develop its own history in my space. I actively try not to ‘design’ my compositions, as it’s much more enriching to discover formal moments in something that was outside my control.

Ioana Manolache, Mother’s Knot I, II, and III (2017–2019). Photo courtesy of Ioana Manolache.

What kind of materials do you use?

While I’m not fetishistic about the tools I’m using, I need to know their characteristics intimately to employ them. I think of these materials as tools that allow me to get a painterly effect that matches the object’s properties, as I imagine them. I invest in Old Holland oil paint for the brightest hues; the amount of pigment is high and this has a direct effect on the final painting, allowing me to capture the full range of blue, red, and yellow.

In this series, since it really is grounded in these primary colors, do you ever get tired of using the same three colors?

That’s a great question, and this is actually my first time completing a series in this way. I actually really enjoy the simplicity of the idea, but really because [the flags] are such poor quality, so it gives me a lot of range.

It’s not as if pure pigment comes straight out of the tube.

Right, and that’s what attracted me in the first place to these flags, covered in plastic. You can see through the perforated holes of the plastic, a glimpse of the truer-color beneath, and so depending on the opacity, it changes the color. There is no such thing as a “true blue” or “true red,” which is a perfect metaphor for these flags.