Archaeology & History

Forgotten Paintings Rediscovered in Mexican Church Restoration After 80 Years of Obscurity

The hagiographic works are rarely found in the Michoacán region.

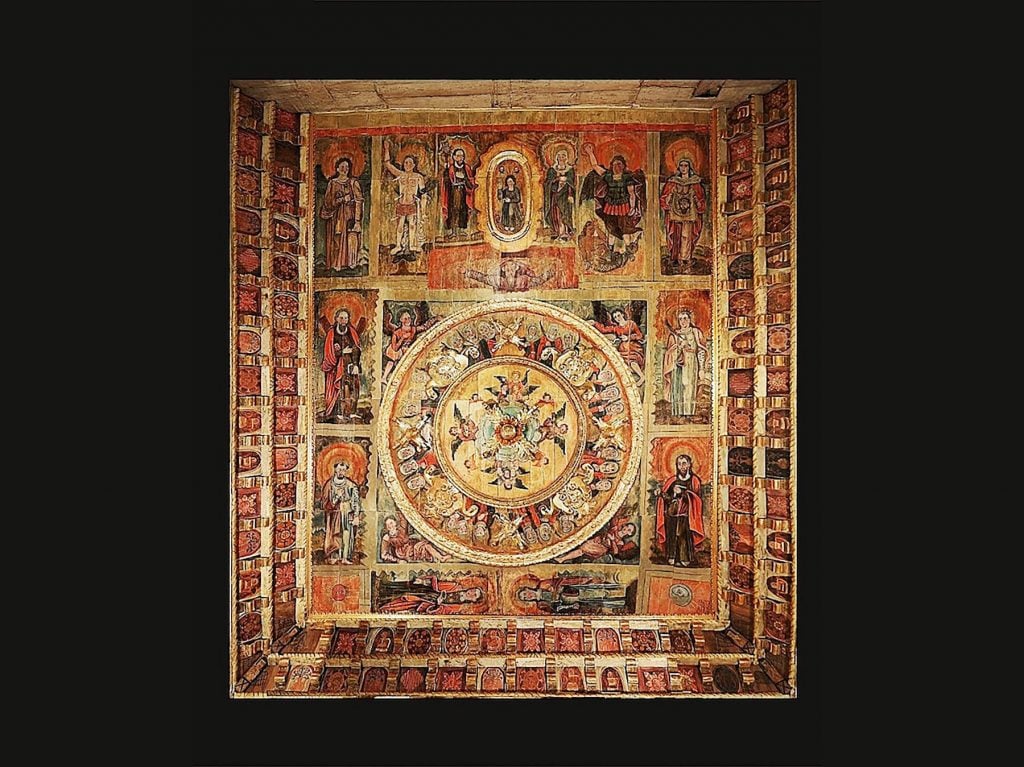

For decades, the interior of the Temple of Our Lady of the Assumption, a church in the town of Santa María Huiramangaro in Mexico, stood stark white, with blue accents. But the parish was not always so bare. A new restoration has revealed a host of resplendent 16th-century religious paintings that once spanned the ceiling of the historic church.

The project, undertaken by participants including the Ministry of Culture of the Government of Mexico and the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), dispatched a team of professionals to conserve the roof of the church. What they discovered instead were ancient images of saints and martyrs—hagiographic works rarely found in the Michoacán region—which had been painted over during the 1940s.

The work, said Laura Elena Lelo de Larrea López, expert restorer at the INAH Michoacán Center, in a statement, “allowed us to recover an extraordinary work on the horizontal roof of the main altar, and to discover the rich artistic, technical and iconographic evolution that has marked this religious site.”

Presbytery of the Temple of Our Lady of the Assumption, Santa Maria Huiramangaro. Photo: Ruber Dan Cázares Herrera.

The Temple of Our Lady of the Assumption was constructed in the early 16th century, when Santa María Huiramangaro was designated a district head, overseeing the communities of San Juan Tumbio, Zirahuén, and Ajuno. The building reflected the architectural styles of Mudéjar, which featured ornate motifs believed to have been originated by Muslim craftspeople in the 13th century, and Plateresque, a late-Gothic and early Renaissance aesthetic imported by the Franciscans.

During restoration work, three pictorial layers of religious iconography were uncovered on the church’s ceiling. The oldest, from the 16th century, saw the use of tempera paint, which was applied in thin glazes to depict various characters corresponding to Saints Paul, Peter, Agatha of Cantania, and Catherine of Alexandria, as well as baby Jesus in Franciscan habit. The works were retouched with oil paints in the following century, adding volume and colors to the depicted figures’ clothing.

Saint Catherine of Alexandria with three polychromes from different periods. Photo: Gabriela Contreras González.

When water ran dry in the region in the 17th century, the church fell largely into disrepair, as Santa María Huiramangaro lost its capital status. “The misfortune was a blessing in disguise, in terms of conservation,” said Lelo de Larrea López, “since, not having the resources to renew its religious furnishings, the parish priests of the Temple of Santa María preserved its Plateresque ornaments, and with it much of the morphology with which it was configured.”

Still, experts uncovered evidence of a restoration effort in the 20th century. Acrylic paints were deployed to touch up the faces of the saints that, according to INAH, while faithful to the original drawings, “were primarily intended to embellish the ornamentation of the presbytery.”

Polychrome roof under construction. Photo: Gabriela Contreras González.

During remodeling work in the 1940s, the iconography on the church’s roof was painted over in white, with blue designs. The repainting, noted Lelo de Larrea López, “caused an alteration in the appearance of the place.”

The latest conservation removed the repainted layer and restored missing portions of the paintings. Additionally, the ceiling was cleaned of dust and animal droppings, reinforced with joints and wood grafts, and fumigated to deter wood-eating insects. Other roof elements, such as corbels, partitions, and Franciscan cord carvings, were also given a refresh.

Polychromy of corbels, partitions, and Franciscan cords. Photo: Gabriela Contreras González.

The work marks the latest phase in a major restoration of the Temple of Our Lady of the Assumption, which began a decade ago with a focus on its main altarpiece. Despite a dismantling (undertaken to tackle a collapse in the church’s rear wall), conservators found the artifact in a well-preserved state. Over 2022 and 2023, they addressed damage to its cornices and carvings, and undid a repainting job to reveal its original gold leaf and polychrome.

The team plans to turn to the church’s other altarpieces in the next stage of the project.