Art & Exhibitions

New York’s Last Payphone Kiosk, Removed from Midtown Last Month, Has Officially Become a Museum Artifact

The piece of urban history was immediately put on display at the Museum of the City of New York.

The piece of urban history was immediately put on display at the Museum of the City of New York.

Sarah Cascone

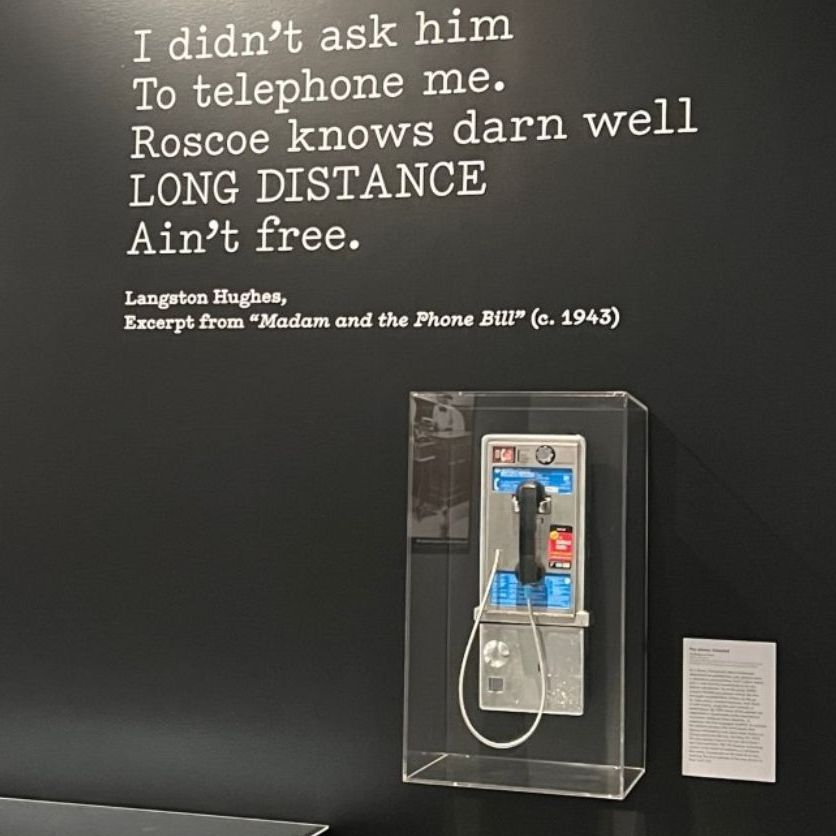

Last month, New York City removed its last payphone kiosk, a relic of an analog age that in 2022 is more of a museum piece than a functional object. So it’s fitting that the phone immediately made its way into the collection of the Museum of the City of New York, where it is now on view in an exhibition celebrating the city’s pre-digital era.

Originally located at Seventh Avenue and 50th Street, the pay phone was ripped from the sidewalk following a ceremony attended by a crowd of journalists and curious onlookers on May 23.

There had always been maintenance issues with payphones, and vandalism and theft meant they were often broken, especially in the 1970s. But these coin-operated telephones were an essential utility for busy New Yorkers for decades.

“In terms of New York City history, payphones were an incredibly important for communicating and staying connected in a really fast-paced city of pedestrians and dynamic street life,” MCNY curator Lilly Tuttle told Artnet News. “You were able to make a call on every corner.”

A man poses with the last payphone kiosk in New York City. Photo courtesy of LinkNYC.

In the early 2000s, New York City had around 30,000 payphones, but that number has rapidly dwindled over the past seven years as they’ve been replaced with LinkNYC kiosks.

The payphone may have the edge when it comes to nostalgia, but LinkNYC is the clear winner when it comes to utility.

The kiosks offer free WiFi and free calls throughout the U.S. (no need to dig up a quarter from the bottom of your wallet), as well as screens featuring rotating displays of ads, artworks, New York city history, and current news. And you can even use them to charge your cell phone.

It was actually thanks to LinkNYC that MCNY was able to acquire the last payphone. The company, which had worked with the museum on some of its on-screen content, reached out to ask if the phone might be a good fit for the collection.

The last payphone kiosk in New York City is now on view at the Museum of the City of New York. Photo courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

“It was being uninstalled with great fanfare just as we were opening this show about pre-digital analog technology,” Tuttle said. “It was a convenient and fortuitous coincidence.”

The phone was installed last week at the entrance to the exhibition, titled “Analog City: NYC B.C. (Before Computers).”

“We spend months and months planning and designing exhibitions, and it just so happened that we had the perfect spot for it right outside the main gallery,” Tuttle added.

The museum exhibition memorializes this bygone era, and the role of technologies such as typewriters, pneumatic tubes, and even note cards and slide rules in the city’s finance, news, and real estate industries.

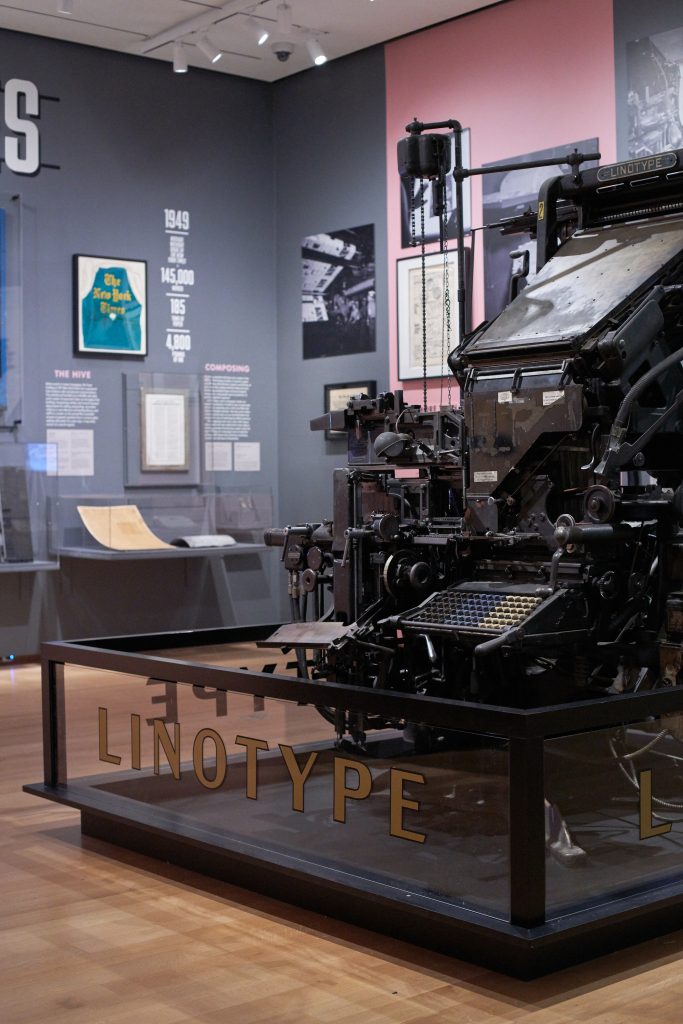

A Linotype machine on view in “Analog City: NYC B.C. (Before Computers)” at the Museum of the City of New York. Photo courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

One artifact on view is a Linotype machine like the ones used by the New York Times, starting in the 1870s, to set type for its newspaper pages, one line at a time, melting down the lead metal type after each issue was printed.

“Prior to this, all printed materials had to be laid out by hand using individual letters. It was incredibly labor intensive,” Tuttle said. “With the Linotype, the paper could print more pages and more frequent editions. It allowed for an incredible boom in the amount of printed materials that were available around the world, and for expansion of the news media as well as literacy.”

Press room of the New York Times. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress, Prints and Photgraphs Division.

The show may also cause visitors to consider the importance of items they’ve never given a second thought to, like the humble filing cabinet—which was actually groundbreaking in its time.

In something of a ripple effect, the adoption of the typewriter led to the production of paper in standardized sizes that could be used in the machine. That, in turn, made it possible to store paper in a standardized way.

“We have a photograph an office where paper is stored horizontally, it’s rolled up, it’s placed into a million little cubby holes in a giant desk—and then we have an example of a file cabinet, which allows you to not only store copious amounts of paper, but also to organize and access that paper,” Tuttle said.

And while the revolutionary nature of the filing cabinet may be lost on us today, the way it changed our world can still be seen in the terminology used for computer storage, in files and folders.

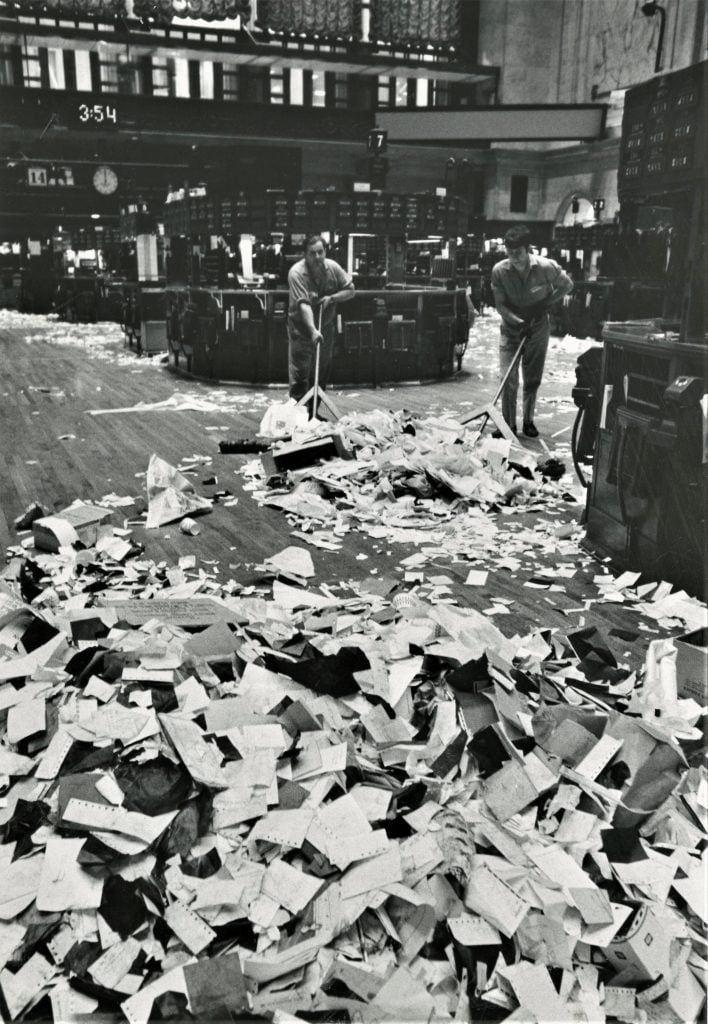

A paperwork crisis at the New York Stock Exchange. Photo courtesy of the NYSE Group Inc.

“The icons on your computer literally look like file folders from vertical filing cabinets,” Tuttle said. “This basic tool for storage and access, that informs subsequent forms of technology.”

“Analog City” is also interactive, giving children and members of Gen Z the chance to test out technology they may have only read about in books or seen in tv or movies.

The payphone, therefore, represents a key addition to the display.

“It was in the heart of Midtown and represents the apex of payphone use,” Tuttle said. “It was probably a real warhorse. That it went away was a symbolic moment representing the end of the era.”

The removal of the last payphone kiosk in New York City. Photo courtesy of LinkNYC.

Though this was the city’s last payphone kiosk left standing, New Yorkers with a dead cell phone battery can still make phone calls at four phone booths that dot the Upper West Side. (Thanks to a strong local fondness for the payphones in the community, the plan is to keep those booths, on West End Avenue at 101st, 100th, 90th and 66th Streets, in operation in perpetuity.)

But the ubiquity of the payphone, once a fixture of the city, is gone forever.

“It’s important to remember how much payphones were part of the urban fabric and the visual landscape of the city up until very recently,” Tuttle said. “The reality is, we didn’t carry around little tiny telephones with us for most of history. In the exhibition, we’re really hoping to remind people that communication used to be very very different in this city. We didn’t have quite the connectivity that cellphones give us, but we were still able to achieve amazing things.”

“Analog City: NYC B.C. (Before Computers)” is on view at the Museum of the City of New York, 1220 5th Avenue, New York, through December 31, 2022.