Art & Exhibitions

The Big Missed Opportunity in the Guggenheim’s László Moholy-Nagy Show

Compared to Moholy-Nagy's own vision, the Guggenheim show feels genteel.

Compared to Moholy-Nagy's own vision, the Guggenheim show feels genteel.

Ben Davis

In 1921, the Hungarian expat László Moholy-Nagy (1895-1946), then in Berlin, signed a “Call for Elementarist Art,” alongside Theo van Doesburg, Hans Arp, and Ivan Puni. It advocated “an art that can be only of our making, that did not exist before us and that cannot continue after us—not a passing fashion, but an art based on the understanding that art is always born anew and does not remain content with the expression of the past.”

Doing his spirit justice, then, was always going to be a heavy lift. How do you convey that arch-modernist sentiment in retrospective form? The guy set a high bar.

The Guggenheim’s just-opened “Moholy-Nagy: Future Present” (May 27-September 7) doesn’t quite live up to the challenge of its subject, though it has a lot to recommend it for Moholy fans. Its subject is remembered for his protean innovations with kinetic sculpture, abstract painting, and experimental photography, as well as for his associations with the Bauhaus and its US-based sequel, the New Bauhaus (later, Chicago’s Institute of Design, which was incorporated into the Chicago Institute of Technology).

Examples of Moholy-Nagy’s ad work for the London Underground. Image: Ben Davis.

The show proceeds in order of biographical chronology. It begins with youthful works like the dense Expressionist charcoal, Barbed-Wire Landscape (ca. 1918), which hints at the awfulness of the First World War as he saw it—he was wounded on the Russian front after serving in the Austro-Hungarian army. It passes through his oft-discussed experiments in “telepainting” (paintings designed so that they could be ordered over the phone, and printed out in a factory) and a selection of his ad work for the London Underground, ending with late paintings and knotty Plexiglas sculptures, done after his emigration to the US in 1937.

Installation view of Moholy-Nagy’s Double Loop (1946) in “Future Present.” Courtesy of Ben Davis.

The main exception to this chronological march of work is also the part where the show is most suggestive. It comes at the top of the first ramp in the Guggenheim’s High Gallery, where you can experience a recreation of Moholy-Nagy’s Room of the Present, an unrealized 1930 proposal, finally built in 2009 by designers Kai-Uwe Hemken and Jakob Gebert based on the original scheme.

László Moholy-Nagy, Room of the Present (Raum der Gegenwart), constructed in 2009 from plans and other documentation dated 1930. Installation view: Play Van Abbe – Part 2: Time Machines, Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, April 10– September 12, 2010. Van Abbemuseum. © 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of Peter Cox, courtesy Art Resource, New York.

The project was planned for a series of art history exhibits in a museum in Hannover, each one meant not just to show the art of a certain period but to construct an installation-style experience evoking the environment in which that art of the past would have been seen.

As its title indicates, Moholy-Nagy’s Room of the Present was intended to be the climax, representing the creative potentials of his own present moment: 1930. It suggests an idea of culture transformed by technology in a way that dissolves hierarchies and barriers, becoming an environment both didactic and dynamic; a multimedia Gesamtkunstwerk (“total work of art”)—or rather Gesamtwerk (“total work”), which was the artist’s preferred term, since he believed in escaping the narrow domain of art.

László Moholy-Nagy, Light Prop for an Electric Stage (1930), as seen as part of the Room of the Present in “Future Present.” Courtesy of Ben Davis.

Undulating metal partitions and perforated screens suggest spatial dynamism and an activated viewer. Walls densely packed with panels show pictures of cutting-edge abstract art, modern architecture, and experimental theater design, all together. Slideshows of parades reveal the energy of everyday modernity.

The entire Room of the Present experience palpably illustrates this artist’s ambition to break out of typical assumptions about how art related to its viewer—indeed, he made his name partly off of his dynamic exhibition designs, which pioneered new ways to illustrate complex cultural ideas, making him, long before the term was coined, a kind of “new media artist.” In his exhibitions, Moholy-Nagy aspired to have, he once said, “[e]verything so arranged that it can be handled and understood by the simplest individual,” with bold graphics, dynamic juxtapositions, “lettering suspended in space, everywhere clear and brilliant colors.”

How genteel the Guggenheim’s “Future Present” feels in comparison to Moholy-Nagy’s own vision!

Writing to Hilla Rebay, founding director of the original Guggenheim (then the Museum of Non-Objective Art) about a presentation of his works there, the artist once quibbled, “I wish… that they could have had a stronger spotlight, as shadows in the transparent pictures would have made their transparency twice as interesting I believe.”

Would the modern Guggenheim meet the artist’s desires about activating his weird paintings on Plexiglas with a vividly electric ambiance? Hard to say. The tony grey atmosphere certainly feels pretty conventional.

László Moholy-Nagy, Papmac (1943). Private collection. © 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo: Kristopher McKay © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, New York.

What I think is a real shame, though, is that the show fails to shine a more dramatic intellectual spotlight on the artist’s world.

As is the custom, each successive biographical section of the show is introduced with an orienting quote. These appear to have been selected to convey a Brain Pickings-level of innocuous inspiration: “New creative experiments are an enduring necessity,” “Not against technical progress, but with it,” etc.

There is also, of course, some scholarly context provided in these orienting texts. For instance, this: “In 1923, Walter Gropius, the founder of the Bauhaus school of art and design, invited Moholy-Nagy to join the faculty… Moholy-Nagy’s appointment emphasized a change in the school’s direction, as stipulated by Gropius, who advocated for the connection between art and technology.”

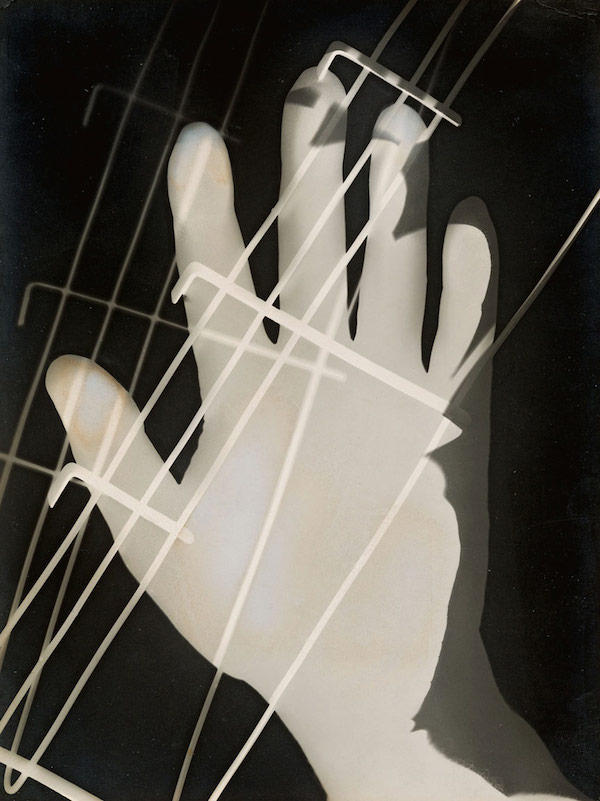

László Moholy-Nagy, Photogram (1926). Los Angles Country Myseum of Art; © 2016 Hattula Moholy-Nagy/VG Bild-Kunst/Artists Rights Society. Courtesy of © 2015 Museum Associates/LACMA.

The reality of this tale is so much more dramatic than it sounds here: 1923 was the German “Year of Hunger,” of the cresting of the terrifying post-war hyper-inflation. The decision to install Moholy-Nagy and turn towards applied design—a U-turn from the arts-and-crafts socialism of the Bauhaus’s roots—was specifically motivated by intensifying political and economic problems, with right-wingers attacking the school as a Commie-Jewish threat to German tradition. The Bauhaus needed to prove its use, and the radical rhetoric of Moholy-Nagy’s technological art could make the case for applied art on left-wing terms that chimed with the school’s original rhetoric.

Why turn down the contrast on this historical drama? Why frame Gropius’s selection of Moholy-Nagy in purely administrative terms? Why make the debate over Bauhaus curriculum about personal taste rather than a tooth-and-nail battle for relevance?

Elsewhere, the show text tells us that Moholy-Nagy was inspired by “the Constructivists, who believed art should reinforce social reform through simple, minimal forms in order to reflect the modern industrial world,” or that Moholy-Nagy “also made photomontages in a nod to the political and provocative imagery of Berlin Dada.”

“Social reform;” “the modern industrial world;” “political and provocative imagery.” These are all evasions, euphemisms designed not to frighten the tourists: All the artists in question identified as outspoken lefties, which meant in those days some form of capital-C Communist. They either believed that art should join the Soviet construction of a worker’s state (i.e., Constructivists), or that art was a weapon in a class war that was then quite literal (i.e., German Dada).

Installation view of “Moholy-Nagy: Future Present” at the Guggenheim. Image: Ben Davis.

In another 1923 “Manifesto,” this one signed with Ernő Kállai, Alfréd Kemény, and László Péri, Moholy-Nagy declared severely that a truly radical art “can be fully realized only within the framework of communist society,” and commanded that, “artists must fight alongside the proletariat, and must subordinate our individual interests to those of the proletariat.” Now there’s a quote for the wall!

Moholy-Nagy’s influential innovations didn’t happen in a historical vacuum, nor was the history around them incidental. It took massive social upheaval to impel this kind of artistic break with the past. Without understanding that fact, the art just becomes pretty stuff on the wall rather than tools for understanding either the real dramas of our past or the real struggles of our present.

The capitalist societies of Europe stood completely discredited by the cataclysm of WWI and the chaos that followed; the full horrors of Stalinized Communism remained in the future. At this historical moment, the technological modernization needed to overcome underdevelopment and the social revolution needed to overcome the old political order were intimately linked in the political imagination. Turning away from the “bourgeois” conventions of salon-based fine art in order to reimagine the use of technological media could be seen as being in solidarity with industrial workers “seizing the means of production;” at the same time, artistic reinvention could be seen as having a vital political role of its own in humanizing the new social order.

“This is our century: technology, machine, Socialism. Make your peace with it; shoulder its task,” Moholy-Nagy wrote in “Constructivism and the Proletariat,” in 1922. “Because it is your task to carry revolution toward reformation, to create a new spirit that will fill the empty forms cast by the monstrous machine.”

Installation view of works in “Moholy-Nagy: Future Present.” Courtesy of Ben Davis.

Today, the notion that trick photography might help bring the revolution seems both fanciful and quixotic. But then again, we’ve lived through the rise of new technology and the social hopes invested in it, only to see for ourselves how those hopes were misplaced—it is clear that the internet does not eliminate all social barriers. And the image of actual social revolution was infinitely closer in Moholy-Nagy’s day.

Still, the idea of the innately revolutionary significance of such experiments was a false investment. And just as, in our day, some hippie DIY evangelists ended up pivoting to be the court philosophers of Silicon Valley (going from “counterculture to cyberculture” as Fred Turner puts it), Moholy-Nagy would go from literally wearing red overalls in solidarity with the workers during his Bauhaus years to becoming, after the harrying professional peregrinations brought on by the rise of the Nazis and European exile, the director of Chicago’s New Bauhaus. There, he helped to mainstream the arch-capitalist instrumentalization of art: industrial design.

Moholy-Nagy’s idealism remained—though in a form slightly less militant and more philosophical. In 1946, he could still imagine that getting students to understand subtle relationships of artistic value was a step “leading towards a biologically right living; towards a city-land unity”—that is, a reimagined aesthetics still prefigured, for him, a Utopian social order.

And he would stand until the end against the divorce of design from an ethical worldview. He still saw the place of the “artist” as being to offer moral guidance to the forces unleashed by technology. In the face of his leukemia, when it came time to look for a new director of the Institute of Design, he urged that the candidate have an artistic and not just an administrative background: “Otherwise the school will be turned into just another engineering school of which there are much too many in the country.”

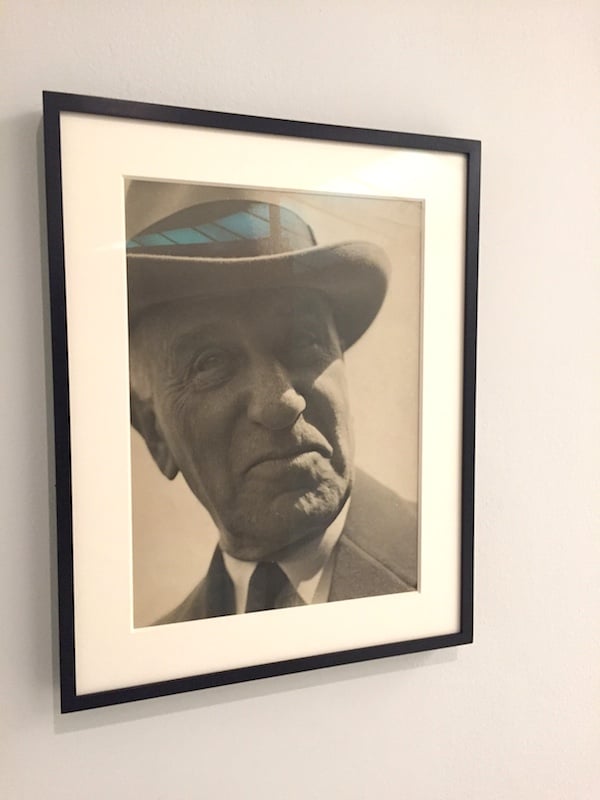

Moholy-Nagy, Photograph (Solomon R. Guggenheim) (ca. 1930). Courtesy of Ben Davis.

The truth is that, though the work in “Moholy-Nagy: Future Present” is cool and even thrilling to look at en masse, there are precious few works that resolve into real iconic, singular images. When it comes to his famous “telepaintings,” for instance, critics then and now talk about how pioneering the idea of remotely created art was, rather than its specific forms, which are by-the-numbers Constructivism (literally: he claimed to have laid the design out on graph paper so he could send the data over the phone).

The case is similar with a lot of his stuff: It is best understood as the product of a flow of ideas, an experimental process of working things out, digging into the potential of new materials and trying to put them together in new ways. That may be why Moholy-Nagy’s genius shines through most in his exhibition designs. It is also why how his art is framed as part of an entire process of thought is so important.

In 1922, in his essay ”Production—Reproduction”—probably his most famous text in a lifetime of texts—he reiterated his criteria for success: “Creative activities are useful only if they produce new, so far unknown relations.”

László Moholy-Nagy’s prognostications probably seem naïve today—but then, the very evasions of this Guggenheim retrospective prove, to me at least, that there are still real lessons to be learned from him, and that, whatever expansions there have been in how we think about art, we haven’t quite moved beyond the pitfalls of “bourgeois” culture as he saw them. Because that’s how you can sum up one criticism of this show: The Moholy-Nagy it gives us is just a little too bougie.

“Moholy-Nagy: Future Present” is on view at the Guggenheim, through September 7, 2016