Olivier Gabet had a good job—one that he had fought hard for—at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. But when the seasoned museum professional Laurence des Cars called him to see if he would join her in helping to create a new museum in Abu Dhabi from the ground up, the decision was easy.

“Overnight, I left my great job,” he recalled. “I knew that with her, it was going to be fascinating.”

This is a recurring theme in conversations about Des Cars, 54, who will take over the Louvre in Paris this fall. When she calls, you would be wise to pick up the phone.

A renowned expert in 19th-century art and the current president of the Musée d’Orsay and the Musée de l’Orangerie, Des Cars will be the first woman to lead the world’s largest museum. Her nomination was a surprise to many observers in the French media, who expected the museum’s current president, Jean-Luc Martinez, to win his bid for a third term.

The job would be daunting under normal circumstances, but throw in damage caused by the pandemic, the still far-off prospect of mass tourism (which makes up most of the Louvre’s ticket sales), plus heated debates around art restitution, “cancel culture,” and the role of encyclopedic museums, and you have a handful of historic proportions.

France’s Ambassador to Russia Jean-Maurice Ripert, Paris’ Musee d’Orsay Director Laurence des Cars, and Marina Loshak, director of Moscow’s Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, attend a press conference on signing the agreement between both museums. (Photo by Alexander ShcherbakTASS via Getty Images)

Luckily for the Louvre, Des Cars has a record of plunging fearlessly into dizzying challenges—and while she’s at it, attracting a host of talented recruits who are willing to quit lucrative jobs around the world to work alongside her. We spoke to a number of former colleagues to get a sense of what is in store for one of the most closely watched ascensions to the Louvre in memory.

A Powerful Leader

The child of an upper-crust family of writers, Des Cars studied art history at the elite École du Louvre. She organized a number of important exhibitions of 19th-century art, but gained global prominence as scientific director of the France-Muséums agency. It was in that role that, in 2007, she was tapped to lead the development of the Louvre Abu Dhabi, the more than $1 billion project that leases the Louvre’s name.

Olivier Gabet, now director of the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris, worked with Des Cars on the high-profile project. Ahead of its opening, the museum was intensely criticized for seemingly selling out French culture to the United Arab Emirates, but has since been met with warm reviews.

“It was a major project, steeped in political and diplomatic meaning, and no small feat to create a museum like that from nothing,” Gabet said. He remembers how Des Cars would reassure him, repeating, “We must not be afraid.”

“When she says that to you, you don’t want to believe otherwise. She has that in her. There’s never arrogance, but there’s a lot of assurance,” he said. “And she was right: there is really nothing to fear.”

Louvre Abu Dhabi exterior. © Louvre Abu Dhabi, Photography: Mohamed Somji.

Des Cars has offered a similar message to women, urging those who “hesitate to apply for positions of responsibility” to “have confidence in themselves, without doubting their legitimacy,” she said, speaking to France’s ministry of culture in March.

Sylvie Patry, the Musée d’Orsay’s chief curator, has experienced Des Cars’s approach firsthand. “We don’t feel limited as a woman, or ever tell ourselves, ‘oh la la, that’s too important a position for me,’” Patry said. “She’s someone with a vision, who is inspiring, and she doesn’t ever give up…. It pushes you forward.”

In a country that still bristles at the idea of quotas, Des Cars’s supporters are also quick to point out that her own appointment was based on her unique qualifications rather than her identity. “There’s catching up that needs to be done in terms of women [in leadership positions], but she was not simply chosen because she’s a woman,” said Sébastien Allard, director of paintings at the Louvre, who co-wrote a seminal book with Des Cars about 19th-century art.

Nevertheless, Allard acknowledged, “it’s a strong and necessary symbol” to finally have a female director at the Louvre, where half of department heads are women.

Background in Scholarship

Colleagues say Des Cars is distinguished by her top-tier academic bona fides, her strong work ethic, her sense of deep responsibility, and her managerial panache, combined with a rare understanding of people, the world around her, and a passionate curiosity for the arts. It doesn’t hurt, either, that she has a good sense of humor and has been known to do keen imitations of French politicians and celebrities.

“We laugh a lot, and for me, it’s really precious to share in her great sense of humor, which also frees us to speak our minds,” Patry said.

As a manager, “she is able to understand everybody’s reasons,” said Donatien Grau, head of contemporary programs at the d’Orsay. “That’s what makes her a remarkable people-person. Institutions are not just ideas. They are made of people…. She understands every person, as well as understanding the idea.”

Visitors look at a painting by Jean-Leon Gerome during the exhibition “Black Models: From Gericault to Matisse” at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris on March 25, 2019. Photo: Francois Guillot/ AFP via Getty Images.

Colleagues noted that while Des Cars is a 19th-century expert, her broad interests, including in pop culture and contemporary art, make her well positioned to expand the Louvre’s audience.

Emblematic of her boundary-breaking approach is the d’Orsay’s landmark 2019 exhibition “Black Models: From Géricault to Matisse,” which some say attracted a more diverse audience than any major Parisian exhibition in recent memory.

The show, an expanded version of an exhibition that first appeared at the Wallach Art Gallery in New York and co-organized by curator Denise Murrell, examined the role of Black subjects and models in French art history, pairing blockbuster paintings with little-known artworks. Its popularity “proves you don’t have to dumb-down to bring in audiences,” Grau said. “It’s actually the opposite.”

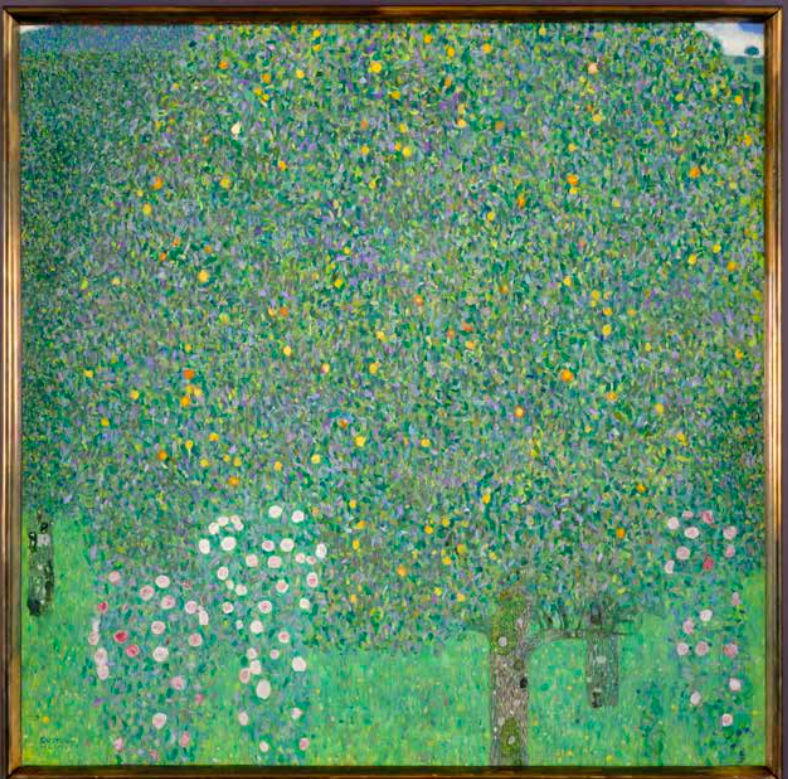

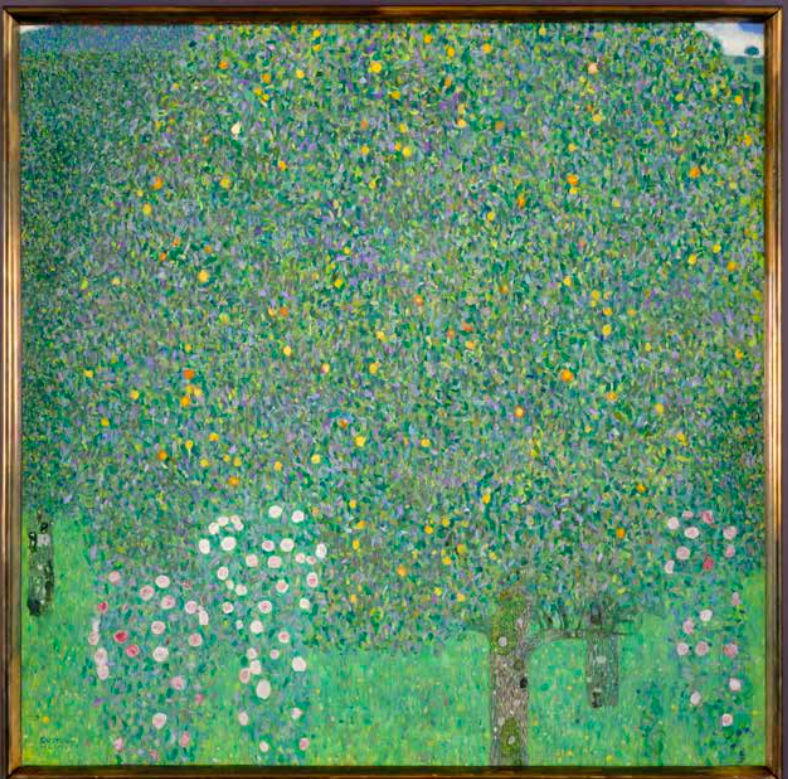

This spring, the director also initiated the restitution of Gustav Klimt’s Rosebushes Under the Trees to its Austrian-Jewish heirs. She is expected to continue to support research into restitution at the Louvre. “Laurence des Cars and I are from a generation that always had the idea that you had to return spoiled works,” Allard said. “Restitution is part of our DNA, and it’s also [our] responsibility and a personal conviction.”

Gustav Klimt, Rosebushes Under the Trees (1905). Courtesy the French Ministry of Culture.

Observers paint Des Cars’s nearly four years at the Musée d’Orsay as a picture of “openness” that expanded what the museum could be, complete with the introduction of new media, greater dialogue with contemporary art, innovative online programming, and educational initiatives.

Her earlier work on the Louvre Abu Dhabi, where she handled everything from archeology to geopolitical relations, “considerably enlarged her point of view, and she injected that into the d’Orsay,” Gabet said. “Thanks to her very strong intellectual and cultural foundations, she can allow herself to break new ground with a lot of freedom and audacity.”

While some might argue that pursuing progressive change at an iconic museum like the Louvre is tantamount to rejecting its identity, Des Cars “has manifested a remarkable third way,” Grau said—one where history is studied, acknowledged, and put into the context of the present day.

“The Louvre is not a fortress that only looks to the past,” Allard said. “It’s a museum in the heart of Paris, at the heart of today’s world. It requires a really contemporary outlook, and she has that.”