Art World

‘He Copies Me Much More Than I Copy Him’: Laurie Simmons and Carroll Dunham on 35 Years of Creative Cohabitation

For the first time, the husband-and-wife artists are having concurrent solo shows in New York.

For the first time, the husband-and-wife artists are having concurrent solo shows in New York.

Sarah Cascone

Husband-and-wife artists Laurie Simmons and Carroll Dunham first met in 1977. When they married six years later, they formed the beginnings of one of New York’s most celebrated creative families, balancing their relationship and careers with raising two children—Lena Dunham, the creator and star of the TV series Girls, and younger daughter Grace Dunham.

Now, for the first time, Carroll Dunham and Laurie Simmons are having concurrent solo shows in New York City: Dunham at Gladstone Gallery, where he is showing a new body of paintings featuring naked men wrestling; Simmons at Salon 94, where she has new photographic portraits of women clad only in body paint, as well as at Mary Boone Gallery, which is revisiting her photographs of ventriloquism dummies, which were originally shown, to little acclaim, in the 1990s.

The couple sat down with artnet News in their Williamsburg apartment to talk about their work habits, how they influence one another, and how they’ve balanced their career and family all these years.

Installation view of “Carroll Dunham” at Gladstone Gallery. Photo by David Regen, courtesy of Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.

Carroll Dunham: I don’t remember having any sort of policy [about not having simultaneous shows], but around the time when we started to have opportunities to have exhibitions in New York, we got married and started raising a family. It seemed like a good thing to me that we were on different cycles. No matter how steadily you work, there’s always a strange and specific stress with an exhibition in New York. But this is good too. We didn’t plan it; the astrological situation finally moved to that point.

Laurie Simmons: I think it’s fine. I have no mixed feelings about it whatsoever.

Dunham: We knew for well over a year about these shows. It was kind of a case study in the way that we each work.

Installation view of “Laurie Simmons 2017: The Mess and Some New” at Salon 94 Bowery. Photo courtesy of Salon 94.

Simmons: If I were a painter and you went into my show, you would smell paint. I work right up until absolutely the last second that I can keep shooting. Carroll on the other hand, how many months in advance were you done?

Dunham: I started planning the group of paintings a year and a half ago. I finished several months before the exhibition, partly because I wanted to have the paintings photographed so that the catalogue could be finished for the opening. But I would have finished the paintings then anyway, because I need to live with things for a while.

Simmons: When I had my mid-career survey at the Baltimore Museum in 1997, I shot the picture on the cover of the catalogue a month before I hung the show.

Dunham: I’ve always been aware of the differences in the way that we work. I work over longer periods of time, kind of like a steady slog; Laurie works more…

Simmons: Episodically. I get a real head of steam going and then the show feels like a horrible interruption in a great work period.

Laurie Simmons’s self-portrait with Carroll Dunham. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Dunham: We both have studios at our place up in Connecticut and we work every day when we’re there.

Simmons: We get up so early. It’s so terrible.

Dunham: The way it would look from the outside is, “Dunham wakes up, has breakfast, and goes to his studio for the day. Laurie gets up and eats breakfast, and then answers emails and makes phone calls, and then does something in the studio, and then does something else, and then goes back to the studio.”

Simmons: He may as well be going to work with a briefcase.

Dunham: But I’m often not working when I appear to be working, and Laurie is often working when she doesn’t appear to be. It’s a very different style, but we both work pretty much all the time in our own way.

Laurie Simmons and Carroll Dunham. Photo courtesy of Laurie Simmons and Carroll Dunham.

Dunham: When you live this closely with another artist, for this long, some kind of dialogue is taking place. I’ve been aware almost since the beginning of our relationship that Laurie’s work has an influence on the way I think about images.

Simmons: We did a lecture about eight years ago, just for our own amusement, comparing images from different periods of our work. It was amazing how much of an unconscious dialogue there was, imagistically speaking. What I always like to say is he copies me much more than I copy him.

Dunham: We’ve been sort of living different sides of the same life now for many years. A lot of the big events that can have an impact on your work, like having a kid, happened to us simultaneously. So when you go back to compare, there are these similar growth spurts and fallow periods.

Simmons: When we were first together people were so curious, other artists in particular. They’d ask, “how can you be with another artist? Aren’t you competitive?” I would say, “it’s really not a problem because he’s a painter and I’m a photo-based artist”—which is a patently ridiculous answer. It’s still two artists under the same roof.

Dunham: The art world has these different precincts and we operate more or less in the same precinct. The same people are interested in each of our work. We have most of the same friends. But because you’ve been making photographs and I’ve been making paintings, the ways in which our work can be talked about in relation to each other has been overlooked.

Installation view of “Laurie Simmons Clothes Make the Man: Works From 1990–94” at Mary Boone Gallery. Photo courtesy of Mary Boone Gallery.

Simmons: I find myself hyper-aware of this dialogue between our two shows on 24th Street, of your new work and my much older photographs. Mary [Boone] chose this work of little men, and you have paintings about male relationships. We’ve both had so many shows over the years, what the exhibitions are about is more significant to me than them being on view at the same time. Do they speak to each other in some way?

Dunham: There is a conversation, maybe, between my recent paintings and those works of Laurie’s but it’s happening through some kind of time warp. Twenty years ago Laurie made this work—

Simmons: Twenty-five.

Dunham: Twenty-five years ago. That was at a time when you wouldn’t even necessarily say my work had subject matter. And your work just gestated in my head. There are literally hundreds of possibilities of what might have wound up in that exhibition at Mary’s, given how much work you’ve made over the years that hasn’t been seen.

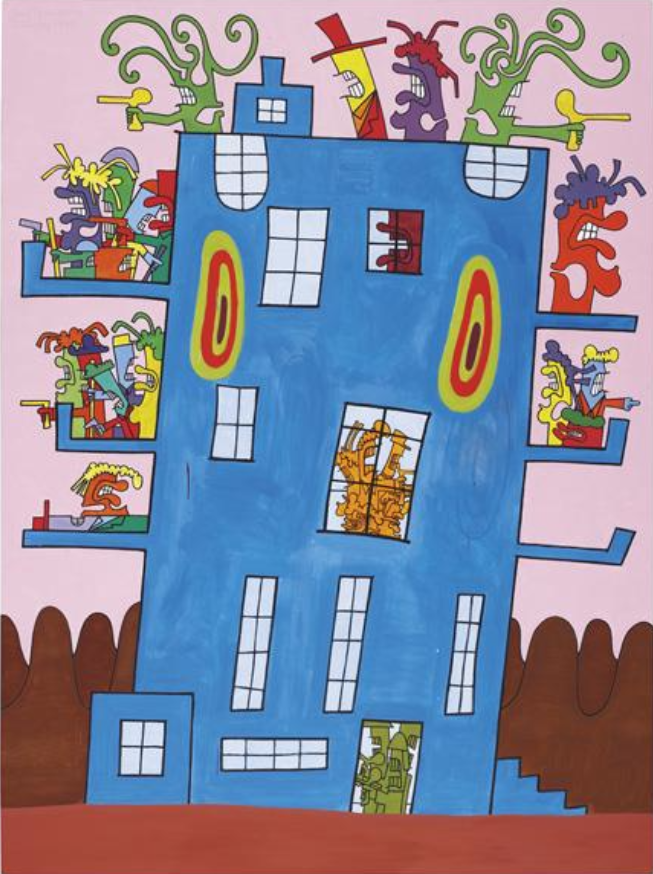

Laurie Simmons, Café of the Inner Mind: Caroline’s Field (1994). Photo courtesy of Mary Boone Gallery.

Simmons: She really shocked me by picking that group of pictures. The reaction in 1994 was not great. I got one lousy review in the New York Times, barely sold it, and put it away. The biggest fan of that work was Carroll Dunham.

Dunham: I was a big booster of that work! It touched me in some way.

Simmons: It was about men, and I had never made work about men before.

Dunham: That seemed really important to me. By that time, we had two daughters and I was living in a world that was utterly feminized. The ventriloquist dummy photographs had a big effect on me.

Simmons: I told you he copies my work!

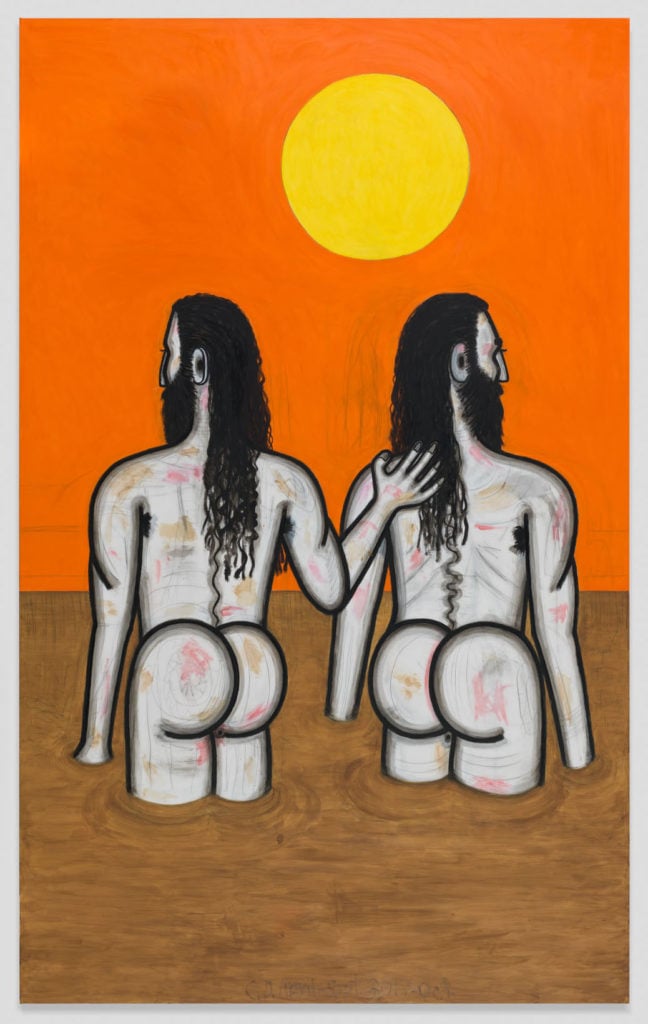

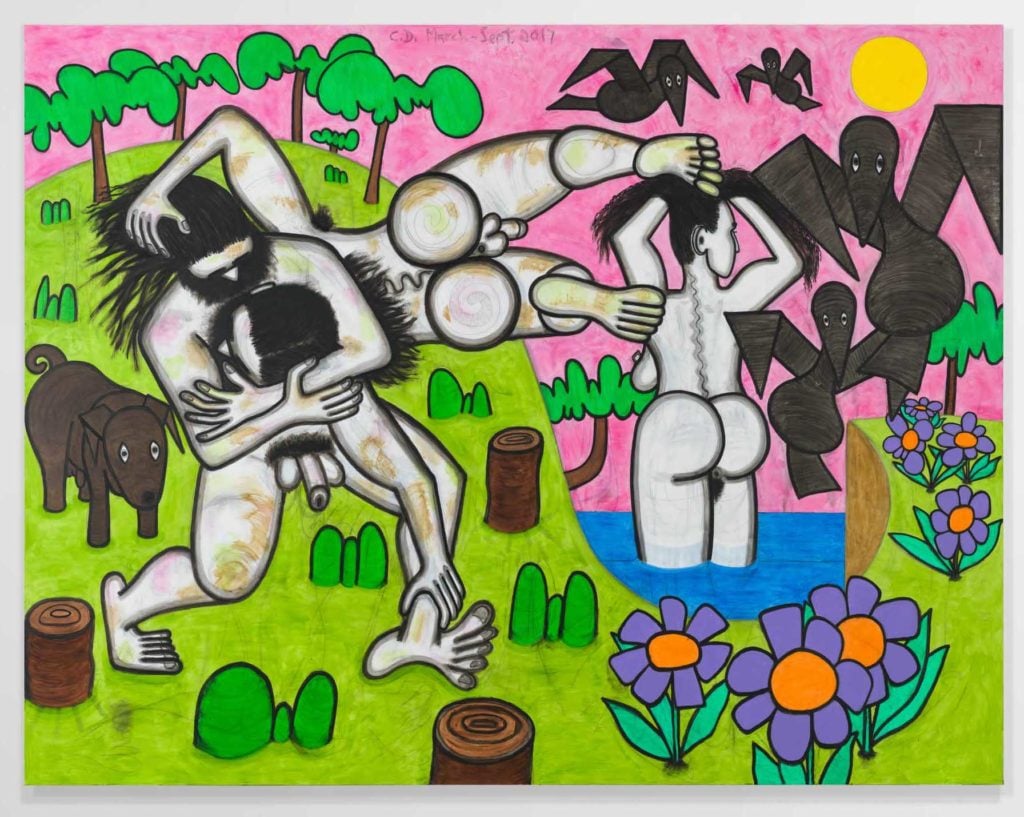

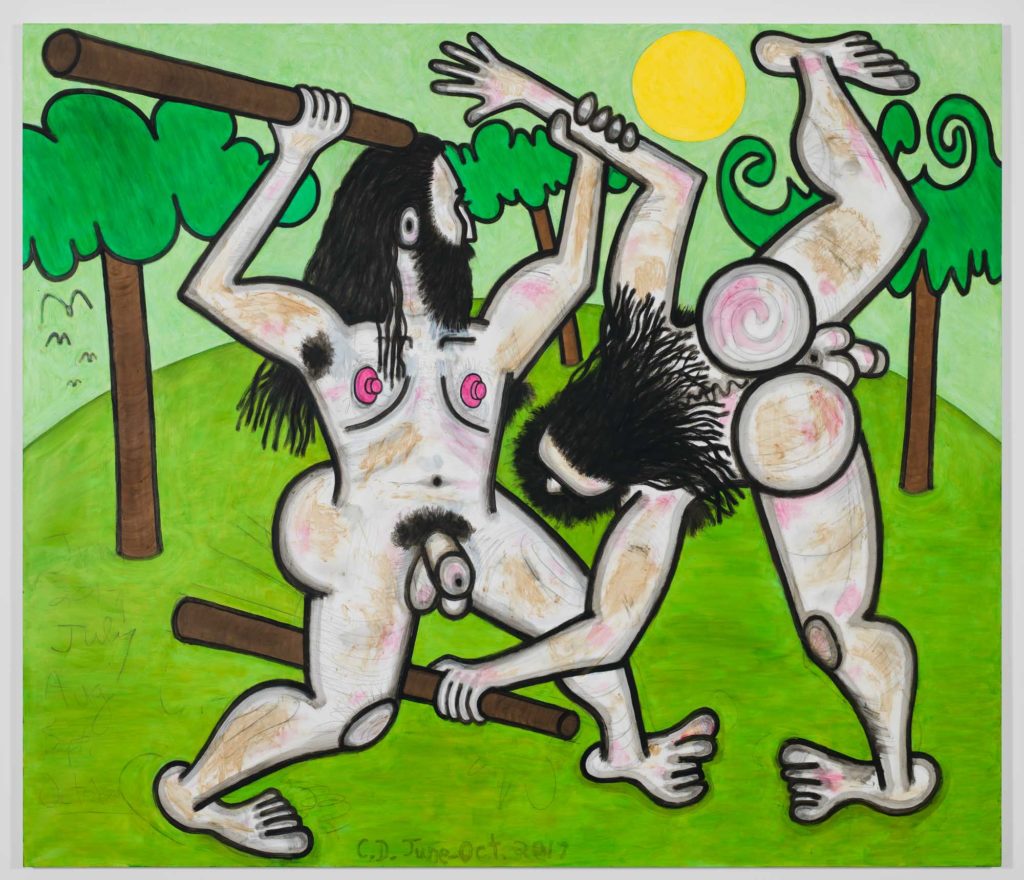

Carroll Dunham, Mud Men (2017). Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels, ©Carroll Dunham.

Simmons: My perception about contemporary art is that there aren’t many paintings about male relationships. I think addressing that is interesting and curious.

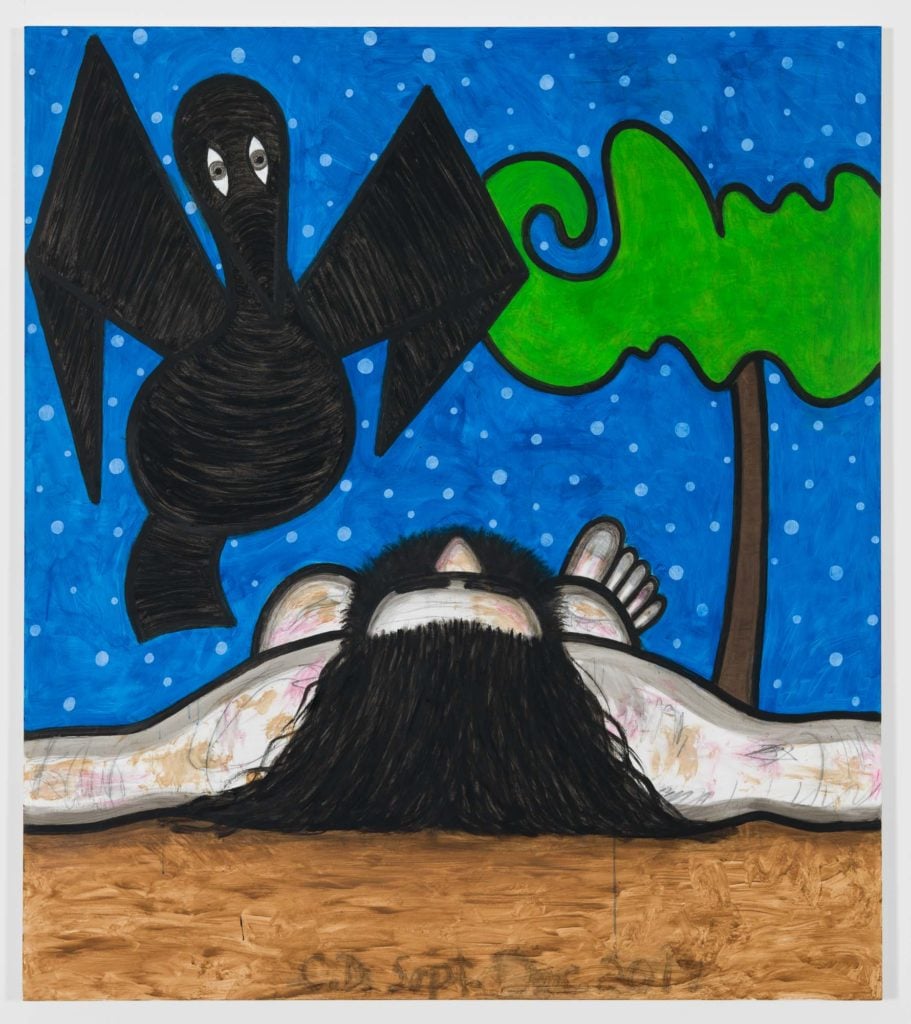

Dunham: I certainly have thought about it after the fact. I don’t think of things that I want my paintings to be “about.” Afterward, I realize what I must have been concerned with. But it started out with my wanting to make a convincing painting of men wrestling.

Simmons: Why wrestling?

Dunham: I had been working for a long time on “Bathers,” of naked women alone in nature. I wanted to use more self-referential imagery of men. I grew up wrestling a lot with my brother and cousins, and watching early pro wrestling on TV with my father. It appealed to me because of the personal memory aspect to the subject, the cultural currency aspect, and also the art-historical aspect, going back to the ancient Greek statues.

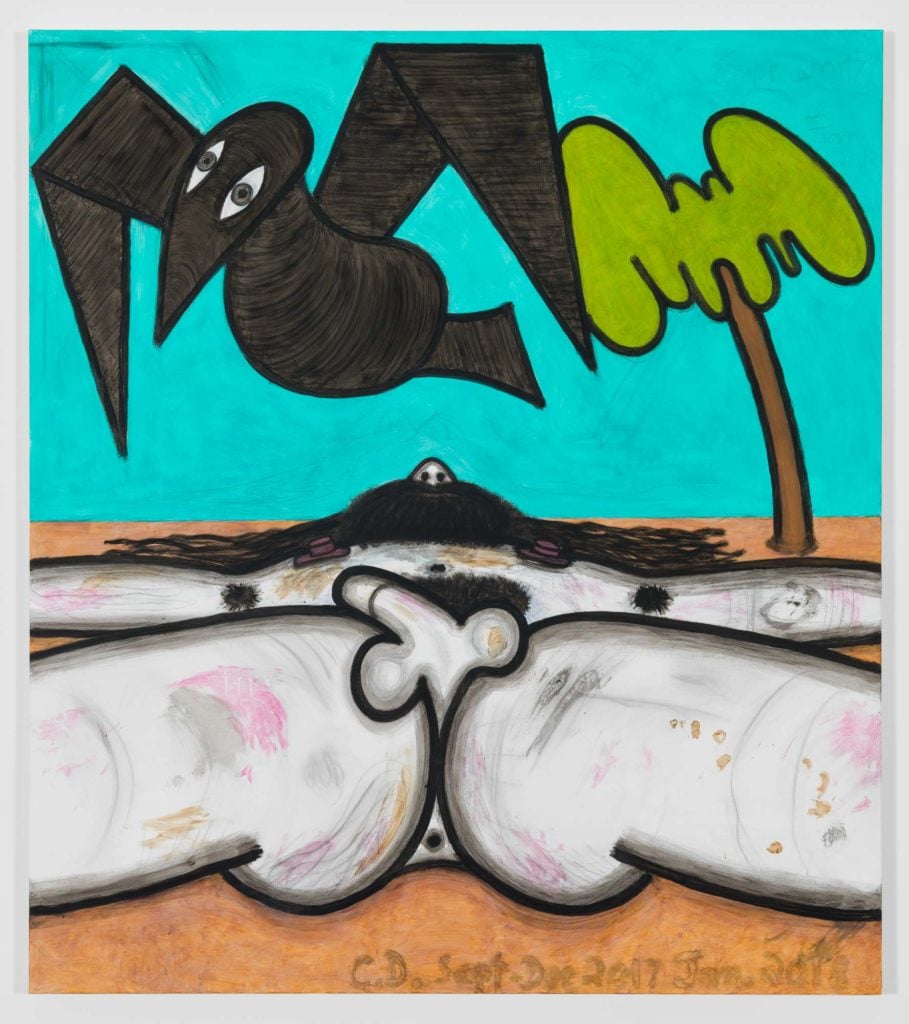

Carroll Dunham, Any Day (2017). Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels, ©Carroll Dunham.

Simmons: A lot of people are finding violence and a homoerotic tinge to the work. How do you feel about that?

Dunham: Wrestling is structured, ritualized violence. It’s a highly ritualized dominance and submission routine. But compared to anything you see on TV or in movies, the idea that my paintings are violent is preposterous. They’re static; it’s all implication.

Simmons: But after years as an abstract painter, is it a relief to have people approach you first on the level of subject matter?

Dunham: Yes. We can talk all day about whether they are violent or homoerotic, but everybody knows what they’re looking at. Nobody says to me anymore, “I don’t know if this looks more like a ginger root or somebody’s cock.” I got so sick of those conversations!

Laurie Simmons, Some New: Hannah (Aqua) (2018). Photo courtesy of Salon 94.

Dunham: With your new photographs, this very complicated, strange painting operation has to happen in order for your subject to be prepared to be photographed. Do you see that as reaching toward painting in some way?

Simmons: Anyone who brings a brush in their hand feels like a real artist to me. When I went to art school, photography wasn’t considered art. Using a camera, there’s really something between you and your subject. I get this real buzz bringing in a real artist to do this beautiful body painting. And number two, I get to do portraiture and desecrate it so it makes itself available to me. Except for the picture of my dog, there is no straight-up portraiture in that show.

Dunham: You have a picture of each of our daughters and other women who are meaningful to you. Would you say the subject of the work is more the person or the paint?

Simmons: I don’t want to just paint a person who isn’t personal to me in some way.

Dunham: In your previous body of work [“How We See,” a series in which Simmons had photo-realistic eyes painted onto the eyelids of fashion models], that wasn’t really true.

Laurie Simmons, How We See/Look 1/Daria (2014). Courtesy the artist and Salon 94.

Simmons: Shooting fashion models was like shooting unicorns. You just get the picture and you kind of can’t go wrong. There’s a reason they are models. It is almost like every angle is beautiful, it works. Some people are very photogenic!

I used to pride myself on wresting emotion from inanimate objects. I never really thought about wresting emotions from a human, or thought that I would try to do that—until now.

Dunham: How did you realize that people could paint cable-knit sweaters on naked people that looked real?

Simmons: I get my information on the most banal parts of the internet. The fact of it is that none of these are my ideas. There was a video that went viral of a woman walking around with painted jeans, seeing who would notice. I watched it a ridiculous number of times.

It occurred to me that there was nothing between that person and the world except a coat of paint. It seemed like an amazing metaphor for being an artist.

Carroll Dunham, Once I Land on Mars (Copied from Grace) (1999). Courtesy of the artist.

Simmons: When each of them were born, I did a portrait for them as a birth announcement. Otherwise, I never sat them down for studio portraits like your parent would if they were a photographer. Just lots of family snapshots.

Dunham: Grace and I went through a period where she was maybe eight years old where we made drawings together. Grace was interested in my paintings and was quite good at imitating them. I liked the kind of crazy eight-year-old Picasso-level brilliance that she brought to bear on the whole thing.

Simmons: Didn’t she come up with one of best names ever for one of your paintings, Once I Land on Mars?

Dunham: That was the title of a novel she wrote that I ripped off for one of my paintings.

Simmons: That’s nice!

Carroll Dunham, Grace Dunham, Lena Dunham, and Laurie Simmons at the New York Premiere of Lena’s film Tiny Furniture at the Museum of Modern Art in 2010. Photo by Eugene Mim, ©Patrick McMullan.

Dunham: But she did title another painting of mine. She came to my studio one day and I said “I can’t figure out what to call it.” She said, “call it Beautiful Dirt Valley,” so I did. I’ve had my kids coming in and out of my studio their whole lives.

Simmons: In terms of family, we always believed in separation of church and state. And then we had Lena Dunham, so forget that. Interestingly, Lena asked me if she could be a subject in my show. I said no several times before I finally relented. And if I did Lena, then I was going to do Grace, because that’s the way it works.

Dunham: They seem like companions to one another, those two photographs.

Laurie Simmons, Some New: Lena (Pink), 2018. Photo courtesy of Salon 94.

Simmons: I think there’s so much to be said for these paintings of men. The subject matter seems to elicit a lot of commentary.

Dunham: When I was working on the “Bathers” paintings, there were so many ways to misunderstand them, especially as pornography. Naked women as a subject in painting goes back hundreds of years, and for some reason has always been given a free pass, a kind of invisibility. Playboy centerfolds are horrifying, but a Titian of a naked woman on a bed is considered a masterpiece—it’s weird.

With my new paintings, I’m aware that there’s this idea that there’s some kind of homoerotic level to them. I just wanted to make paintings of guys wrestling each other. That’s a really pure intention, it’s not a wink wink.

Simmons: I think there’s a real discomfort with seeing male genitalia depicted. People get squeamish.

Carroll Dunham, Left for Dead (3) 2017–18. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels, ©Carroll Dunham.

Dunham: There’s a huge tradition of men painting naked women over hundreds years of European and American art history, hanging in our most important cultural institutions. That’s not the problem. The problem is what do we do now with people’s new awareness of the relationships between men and women that were taken for granted?

Now that it’s all being remade, I don’t think that makes those paintings less interesting or less important. The art history we have is the art history we have. Now we have to go forward, making what seems important to make now.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

See more photos from the exhibitions below.

Laurie Simmons, Some New: Grace (Orange), 2018. Photo courtesy of Salon 94.

Laurie Simmons, Some New: Penny (Harlequin), 2018. Photo courtesy of Salon 94.

Laurie Simmons, Some New: Hayden Dunham (Blue), 2018. Photo courtesy of Salon 94.

Laurie Simmons, Some New: Hayden Dunham (White), 2018. Photo courtesy of Salon 94.

Laurie Simmons, Some New: Andrianna (Red), 2018. Photo courtesy of Salon 94.

Laurie Simmons, Some New: Shirin (Yellow), 2018. Photo courtesy of Salon 94.

Laurie Simmons, 2017: The Mess (2017). Photo courtesy of Salon 94.

Laurie Simmons, Café of the Inner Mind: Dark Cafe (1994). Photo courtesy of Mary Boone Gallery.

Laurie Simmons, Café of the Inner Mind: Mexico (1994). Photo courtesy of Mary Boone Gallery.

Laurie Simmons, Café of the Inner Mind: Gold Cafe (1994). Photo courtesy of Mary Boone Gallery.

Laurie Simmons, Café of the Inner Mind: Chicken Dinner (1994). Photo courtesy of Mary Boone Gallery.

Laurie Simmons, Untitled Band (1994). Photo courtesy of Mary Boone Gallery.

Installation view of “Laurie Simmons Clothes Make the Man: Works From 1990–94” at Mary Boone Gallery. Photo courtesy of Mary Boone Gallery.

Installation view of “Laurie Simmons Clothes Make the Man: Works From 1990–94” at Mary Boone Gallery. Photo courtesy of Mary Boone Gallery.

Installation view of “Carroll Dunham” at Gladstone Gallery. Photo by David Regen, courtesy of Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.

Installation view of “Carroll Dunham” at Gladstone Gallery. Photo by David Regen, courtesy of Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.

Installation view of “Carroll Dunham” at Gladstone Gallery. Photo by David Regen, courtesy of Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels.

Carroll Dunham, Carroll Dunham Green Hills of Earth (1), 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels, ©Carroll Dunham.

Carroll Dunham, Left for Dead (2) 2017–18. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery, New York and Brussels, ©Carroll Dunham.

“Laurie Simmons 2017: The Mess and Some New” is on view at Salon 94 Bowery, 243 Bowery, New York, April 27–June 2, 2018.

“Laurie Simmons Clothes Make the Man: Works From 1990–94” is on view at Mary Boone Gallery, 541 West 24th Street, New York, April 27–July 27, 2018.

“Carroll Dunham” is on view at Gladstone Gallery, 515 West 24th Street, New York, April 20–June 16, 2018.