Art World

A First Look Inside the New Alabama Museum Boldly Confronting Slavery and Its Brutal Legacy

Both projects, conceived of by lawyer, activist, and MacArthur Genius Bryan Stevenson, open this week in Montgomery.

Both projects, conceived of by lawyer, activist, and MacArthur Genius Bryan Stevenson, open this week in Montgomery.

Taylor Dafoe

“History, despite its wrenching pain, cannot be unlived, but if faced with courage, need not be lived again.”

Those words, by the late poet Maya Angelou, greet visitors entering The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration in Montgomery, Alabama. They serve as a thesis statement for the institution and its nearby sibling, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, which commemorates 4,000 lynching victims. Both open on Thursday and both share a common mission: to confront the darkest chapters in American history—from slavery to Jim Crow to mass incarceration—honestly and unflinchingly.

The museum and the memorial, each the first of their kind, were conceived by lawyer, activist, and MacArthur “Genius” Bryan Stevenson. The twin-pronged project was produced by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), the nonprofit human rights organization Stevenson founded in 1994 to fight mass incarceration and racial and economic injustice. (The EJI raised more than $20 million in private donations—many for as little as $20 and $30—to fund the project. Major corporations like the Ford Foundation and Google also backed the initiative, as did philanthropists like Jon and Pat Stryker, who donated $10 million.)

Kwame Akoto-Bamfo, Nkyinkim. Courtesy of the Equal Justice Initiative.

Stevenson says the project was designed to offer a direct counterpoint to the country’s penchant for softening representations of slavery—minimizing its brutality and its racist legacy.

“Our nation has tried very hard to create a picture of slavery that is benign and inoffensive,” Stevenson tells artnet News. “We don’t generally show the chains, the suffering, and the brutality. As a result, we’ve done a poor job confronting the legacy of slavery or acknowledging the shame of white supremacy and racial bigotry.”

Addressing that legacy in a museum setting required both directness and care. While it was essential to accurately capture the horrors of slavery, Stevenson says it was also important to bring visitors to that imagery thoughtfully.

“We’ve been very cautious about graphic images of lynching victims because without care they can dehumanize and distract,” Stevenson explains. “However, people in the US are often so resistant to acknowledging the brutality of racism that for some, those images must be seen. We use technology to blur and distort them until someone chooses to see that violence.”

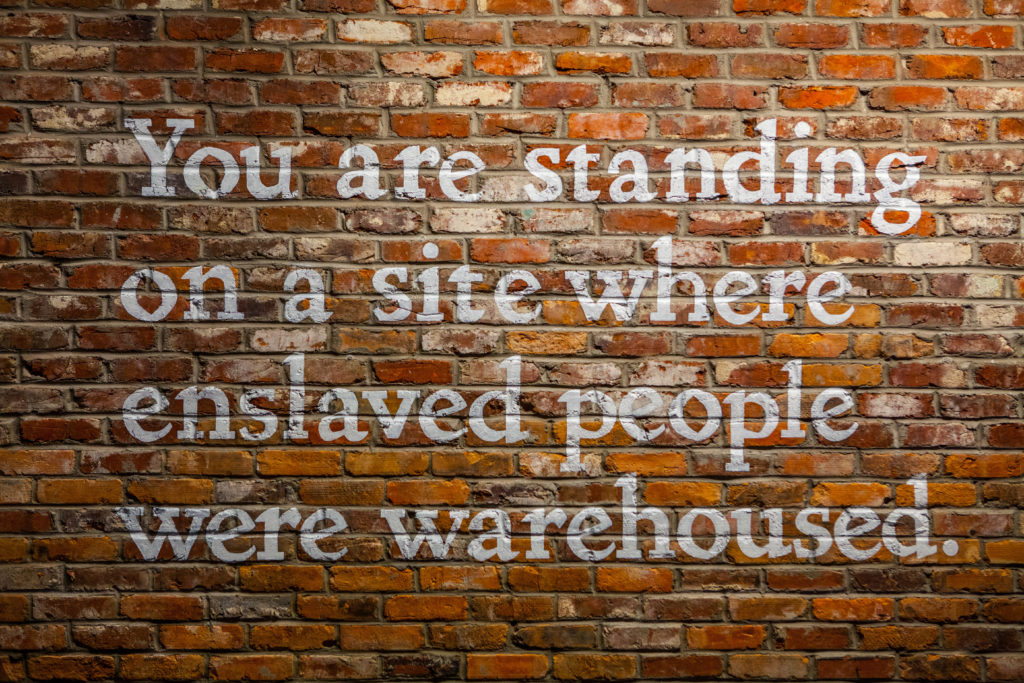

A quote printed in the lobby of the Legacy Museum. Courtesy of the Equal Justice Initiative.

Both the museum and memorial will open with a two-day-long summit of programming featuring figures such as Ava DuVernay, Gloria Steinem, Usher, the Roots, and former Vice President Al Gore. Thousands of visitors are expected to attend.

Stevenson believes the museum will challenge all visitors in a way they’ve never experienced. “This museum will be a new experience for many people in the US because we don’t typically acknowledge our failures or confront our history of racial bigotry,” Stevenson says. “But changing the narrative about the legacy of slavery requires some measure of courage. We’re asking people to be brave. We believe that understanding our history won’t harm us, it will actually empower us to create a better future.”

Below, take a more in-depth look at the memorial and the museum.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama. Courtesy of the Equal Justice Initiative.

Situated on a six-acre patch of land less than a mile from the museum, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice is an open square structure with a connected walkway and awning overhead. Eight hundred six-foot-tall corten steel blocks are suspended from the ceiling—one for each county in the United States where a lynching occurred—with the names of over 4,000 victims of racial terror inscribed on them.

At the entrance, the blocks touch the floor, but as visitors move along through the installation, the floor slowly slants downward giving the effect that the blocks are rising higher. Visitors will wind their way around the monument’s outer rim and inward toward a grassy hill at the center of the monument—a site of reflection.

An interior view of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. The names of more than 4,000 victims are engraved on the 800 steel blocks. Courtesy of the Equal Justice Initiative.

Outside the square monument are an additional 800 steel blocks, duplicates of those that are hanging inside. Eventually, each one will be placed in the county it represents, serving as on-site monuments to the victims.

The memorial has been in the works since 2010, when EJI began researching and documenting thousands of lynchings that occurred in twelve states. The organization’s work culminated in their 2015 report, “Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror.”

The Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration in Montgomery, Alabama. Courtesy of the Equal Justice Initiative.

In the heart of Montgomery—the former capital of the domestic slave trade in Alabama—the Legacy Museum stands on the site of a former slave warehouse and is just steps away from what was once one of the most prominent slave auction sites in the country. From oral history to interactive technology, the data-heavy exhibits combine a variety of media and archival materials to recount the history of slavery, racial terror, segregation, police violence, and mass incarceration in America.

The 11,000-square-foot museum also features a selection of contemporary art, including works by Kay Brown, Elizabeth Catlett, Hank Willis Thomas, and many others.

“Artists help us understand aspects of the human struggle that are difficult to articulate with mere description,” Stevenson says. “Great art can illuminate history and interpret our hopes and fears in ways that can be powerful, beautiful and unforgettable. At the Legacy Museum, we want to employ every narrative tool that can deepen our commitment to human rights and human dignity.”

The majority of the institution’s collection comprises existing works, chosen by Stevenson and his team after reviewing catalogues and speaking with artists. Titus Kaphar’s sculpture Doubt is included, as is Sanford Biggers’s BAM (For Michael). There’s also a new, unseen work by Glenn Ligon that was created specifically for the institution.