Archaeology & History

In Pictures: A New Show Explores Ancient Pompeii Dining Rituals, From Vermin Delicacies to Bone Toothpicks

The eruption of Mt. Vesuvius interrupted Roman diners mid-meal—and this museum has the carbonized food to prove it.

The eruption of Mt. Vesuvius interrupted Roman diners mid-meal—and this museum has the carbonized food to prove it.

Sarah Cascone

The lost city of Pompeii remains a source of fascination nearly 2,000 years after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in the year 79 A.D. buried its streets in a blanket of fiery ash and froze them in time.

Now, the Legion of Honor, part of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, presents the first museum exhibition about the daily life of Pompeii’s citizens, as viewed through the lens of their kitchens and dining rooms.

“Last Supper in Pompeii” travels to the Bay Area from the Ashmolean Museum Oxford and features some 150 mosaics, frescoes, sculptures, household objects, and other artifacts excavated from the ancient city, all speaking to the importance of food and drink in the Roman Empire.

“As it is for us today, food and drink really was a great love of the people of Pompeii,” curator Renée Dreyfus told Artnet News. “The extraordinary treasures on loan in this exhibition come together to tell us of their culinary desires.”

The entrance to “Last Supper in Pompeii: From the Table to the Grave” at the Legion of Honor, San Francisco. Photo by Gary Sexton, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

The wealth and beauty of Pompeii’s villas greets visitors to the show in the form of three sky blue frescoes depicting a verdant garden. They are on loan to the U.S. for the first time from the Archaeological Park of Pompeii. In front of these vibrant panels stands a six-foot-tall white marble statue of Bacchus, the god of wine and fertility, reminding the viewer of Rome’s penchant for a good party.

There are practical artifacts, such as a tiny jar of delicate bone toothpicks, pots and pans, and silver drinking vessels. Then there are more unusual aspects of Roman cuisine on display, including a glirarium, or dormouse jar, a deep, dark ceramic vessel where the vermin would live and feed on acorns and chestnuts to fatten up before slaughter. These plump delicacies might have been served with honey and poppyseeds.

A dormouse jar (right) and other vessels in “Last Supper in Pompeii: From the Table to the Grave” at the Legion of Honor, San Francisco. Photo by Gary Sexton, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

And it’s not just seemingly-strange eating eating habits that might surprise modern viewers. Rather than patronizing expensive restaurants, Pompeii’s upper class ate at home, in villas tended by enslaved peoples.

“The poor people had no kitchens, no enslaved people to prepare food for them, so they would go out to a tavern or a bar,” Dreyfus said. “In our world, it’s the opposite.”

Highlighting Pompeii’s abrupt end is a selection of foodstuffs that were instantly carbonized when the volcano hit. There are figs, plums, dates, olives, lentils, beans, walnuts, almonds, and even a loaf of bread, the latter paired with a wall fresco showing a political candidate handing out bread to curry favor with voters.

A carbonized loaf of bread in “Last Supper in Pompeii: From the Table to the Grave” at the Legion of Honor, San Francisco. Photo by Gary Sexton, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Some frescoes are tributes to popular dishes, like a live rooster painted with the pomegranate it would later be cooked with. A gorgeous dining room floor mosaic presents an array of seafood that might appear at the dinner table—and guests might try to identify as a game during the meal.

“It’s made in a very Greek style with these very tiny tiles that allow every little detail to show up,” Dreyfus said. “It’s really quite extraordinary.”

There is also a selection of erotic art, with frescoes featuring copulating couples and engorged penises, which were symbols fruitfulness, and also meant to bring luck and prosperity.

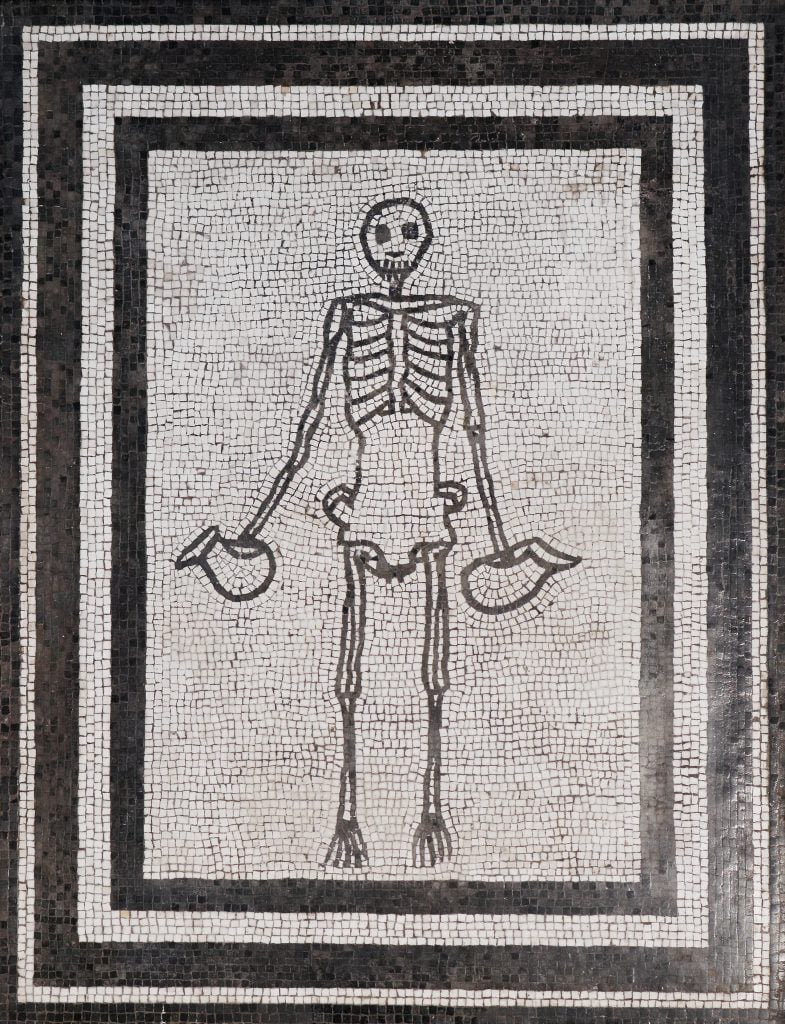

Mosaic of a skeleton carrying two askoi (wine jugs) from Pompeii, collection of the Naples Museum. Photo by Marie-Lan Nguyen courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

But the specter of death looms over the exhibition—and not just because viewers know the city’s fate. One particularly striking mosaic that would have appeared on a dining room floor features a smiling skeleton carrying two wine jugs.

“You wonder what invited guests to a banquet must have thought of this, because it’s a reminder of death,” Dreyfus said. “In their rituals for their dead, the Romans would have banquets. It was a way of sending a person off into what they hoped would be a very happy afterlife, where the banqueting would continue and there would be good food and wine surrounded by friends and close companions.”

The show ends with two dramatic reminders of the violent way in which this opulent world came crashing down.

The Lady of Oplontis cast in epoxy resin. It is thought that she was in her late 30s or early 40s when she died. Photo courtesy of the Antiquarium e area Archaeologica di Boscoreale.

There’s the Lady of Oplontis, a victim of the explosion who died her late 30s or early 40s in a town just 2.5 miles from Pompeii.

When the explosion of pyroclastic flow—magma, hot ash, and gases—overtook the city and surrounding regions, everyone died instantly. The ash hardened around the bodies, and when the soft tissue decayed, it left a cavity preserving their death throes for all eternity. But where most Pompeii casts were made of plaster, the Lady of Oplontis is transparent epoxy resin, allowing viewers to see her bones and golden jewelry.

“We couldn’t send the exhibition without talking about the tragedy, the thousands whose lives were lost,” Dreyfus said.

On the other side of the wall, an animation recreating the cataclysmic eruption and the city’s destruction plays on loop.

It’s like something out of a Hollywood disaster movie—but it was all too real for the people of Pompeii, who saw their world snuffed out in an instant, dining rituals and culinary traditions along with it.

See more artifacts from the exhibition below.

Fresco showing a cockerel pecking at pomegranates, Pompeii, (AD 50–79). Photo courtesy of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.

Silver cup decorated with myrtle sprays and berries (AD 1–100). Photo courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Fresco showing a man handing out bread, perhaps as a bribe for voters (AD 50–79). Photo courtesy of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.

Marble statue of the god of wine, Bacchus, carrying a thyrsus (staff) with a pine cone at its tip, accompanied by his totem animal, the panther, (circa AD 1–100). Photo courtesy of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.

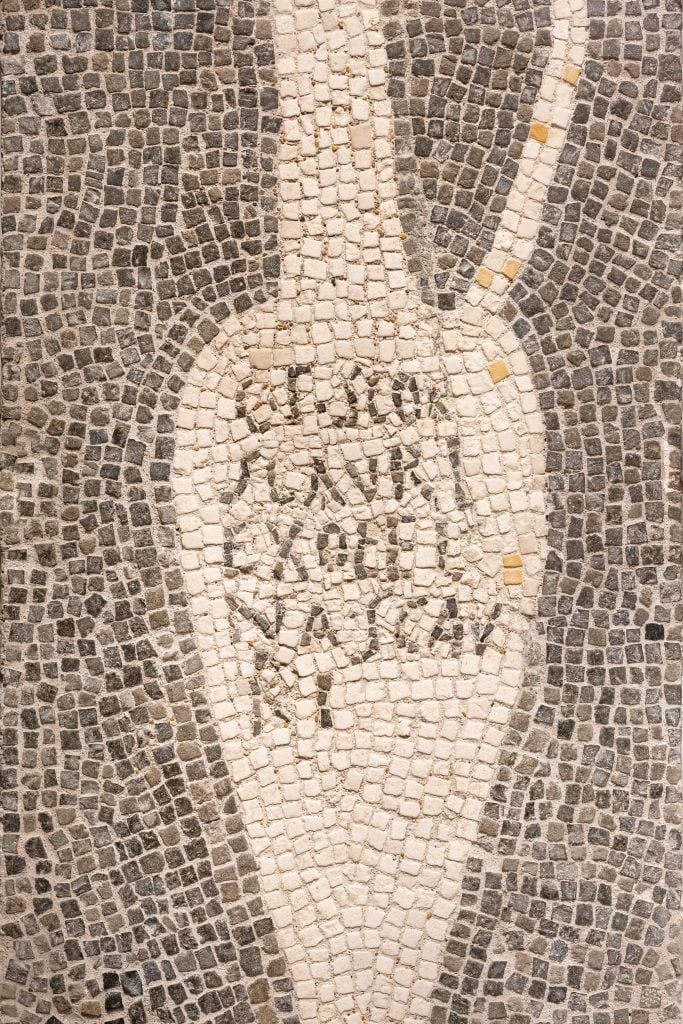

Fresco from Pompeii showing a convivium, or banquet (AD 50–79). In the Latin caption, a woman offers to sing, and a man replies “Yes, you go for it!” Photo courtesy of the Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Napoli.

A doormouse jar (right) and other ceramic vessels in “Last Supper in Pompeii: From the Table to the Grave” at the Legion of Honor, San Francisco. Photo by Gary Sexton, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Detail of a mosaic from “Last Supper in Pompeii: From the Table to the Grave” at the Legion of Honor, San Francisco. Photo by Gary Sexton, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Detail of a fresco from “Last Supper in Pompeii: From the Table to the Grave” at the Legion of Honor, San Francisco. Photo by Gary Sexton, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

A fresco in “Last Supper in Pompeii: From the Table to the Grave” at the Legion of Honor, San Francisco. Photo by Gary Sexton, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Bronze, iron, silver, copper

strongbox with appliques (AD 1–79). Photo courtersy of the Parco Archeologico di Pompeii and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Erotic art from “Last Supper in Pompeii: From the Table to the Grave” at the Legion of Honor, San Francisco. Photo by Gary Sexton, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Shells and carbonized food in “Last Supper in Pompeii: From the Table to the Grave” at the Legion of Honor, San Francisco. Photo by Gary Sexton, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

A fresco in “Last Supper in Pompeii: From the Table to the Grave” at the Legion of Honor, San Francisco. Photo by Gary Sexton, courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.

Statuette of a Lar (household deity) holding a rhyton (drinking vessel) and libation dish (AD 1–100). Photo courtesy of the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

“Last Supper in Pompeii: From the Table to the Grave” is on view at the Legion of Honor, 100 34th Avenue, Lincoln Park, San Francisco May 7–August 29, 2021.