Archaeology & History

Excavations Around Leicester Cathedral in the U.K. Have Turned Up a Roman Shrine Archaeologists Call a ‘Cult Room’

The dig also uncovered Anglo-Saxon artifacts including coins and hair pins.

The dig also uncovered Anglo-Saxon artifacts including coins and hair pins.

Artnet News

While the Leicester Cathedral undergoes major restoration work, excavations around its grounds have uncovered surprising evidence that points to its ancient past.

Researchers from the University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS), who are excavating the area around the church as part of the Leicester Cathedral Revealed project, have discovered a semi-subterranean structure nearly 10 feet below ground, at the eastern end of the cathedral. Within the 13-by-13-foot space, they found painted stone walls and the broken base of an altar stone.

Archaeologists from the University of Leicester excavate a Roman cellar at Leicester Cathedral. Photo: ULAS.

In light of its decorative paintwork and the remains of the altar, the sunken chamber has been dated to the 2nd century, when it likely served as a place of worship during Roman Britain.

“What we’re likely looking at here is a private place of worship, either a family shrine or a cult room where a small group of individuals shared in private worship,” said Matthew Morris, the ULAS project officer who is leading the dig.

The base of a Roman altar stone was found lying broken and face down in the Roman cellar at Leicester Cathedral. Photo: ULAS.

While the surviving altar stone does not bear any inscriptions, such underground rooms have long been linked with fertility and mystery cults, as well as the worship of gods including Bacchus, Dionysius, and Cybele, Morris added.

“It would have been the primary site for sacrifice and offerings to the gods,” he said, “and a key part of their religious ceremonies.”

In the late 3rd or 4th century, the chamber was deliberately dismantled and infilled, as indicated by the site’s rubble.

The Roman altar stone found during archaeological excavations at Leicester Cathedral. Photo: ULAS.

Though the Leicester Cathedral was built in 1086 around the time of the Norman Conquest, folk tales have long circulated that the site served as a place of religious observance during the Roman occupation between 43 C.E. and 410. The legend gained steam in the late 19th century when a Roman building was excavated during the rebuilding of a church tower.

The Leicester Cathedral Revealed project has also turned up more than 1,100 burial remains dating from the 11th to 19th century, in addition to artifacts including coins, hair pins, and pottery shards from the Anglo-Saxon period.

Three Roman coins found during the excavations (from left to right): Coins of the Emperors Vespasian (69–79 C.E.), Tetricus I (271–74 C.E.) and Constantius II (as Caesar under Constantine I, 320s/330s C.E.). Photo: ULAS.

Personal adornments lost by the residents of Roman Leicester, found during the excavations (from left to right): A copper alloy head stud brooch dating to the late 1st or early 2nd century, and two hair pins crafted from animal bone around the 3rd or 4th century. Photo: ULAS

“Given that we’ve found a potential Roman shrine, along with burials deliberately interred into the top of it after it’s been demolished, and then the church and its burial ground on top of that,” said Morris, “are we seeing a memory of this site being special in the Roman period that has survived to the present day?”

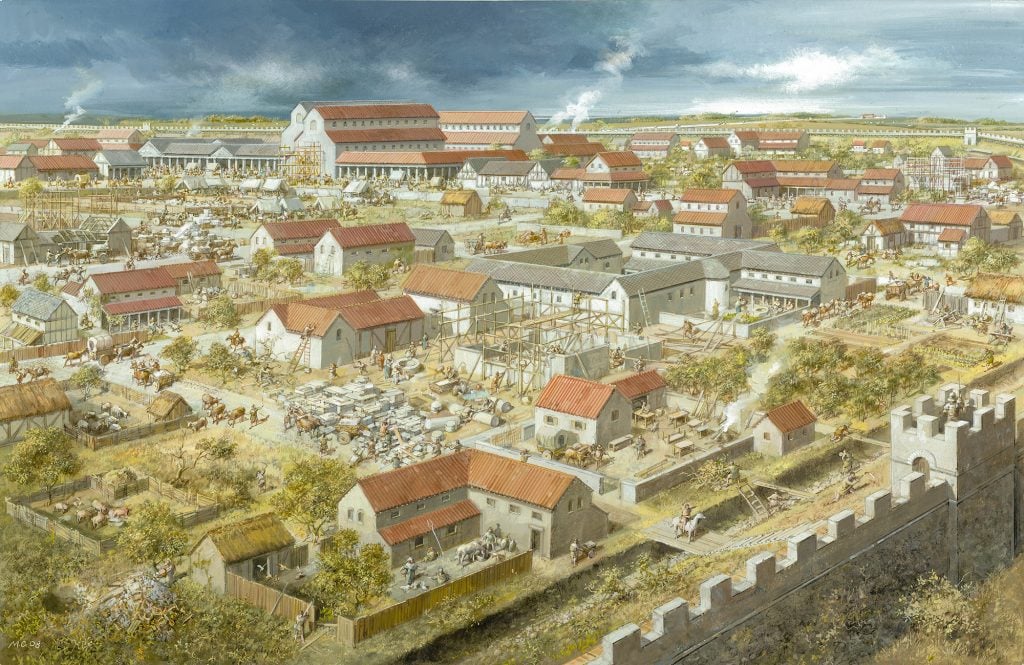

Leicester was once home to a Roman settlement, Ratae Corieltauvorum, which, as indicated by a major excavation in 2016, contained elaborately decorated houses, public baths, an open marketplace, and two temples. The ULAS team is hoping this latest project might provide a window into the region’s deep history, perhaps going back to the early Iron Age.

An artist’s rendering of Ratae Corieltavorum from the north-west, as it may have looked during the late 3rd century. Photo: ULAS / Mike Codd.

“The project allowed us to venture into an area of Leicester that we rarely have the opportunity to investigate, and it certainly did not disappoint,” said John Thomas, deputy director of ULAS.

With further analysis and study, he added: “We’ll have a much clearer idea of what was happening on the site in the Roman period, when the parish church of St. Martins was founded, and a unique insight into the story of Leicester through its residents who were buried here for over 800 years.”