Books

A New Book Explores the Mysterious Genius of Leonardo

"What does our da Vinci cult tell us about ourselves, in the 21st century?" asks the author of a new book that re-mystifies the famous artist.

"What does our da Vinci cult tell us about ourselves, in the 21st century?" asks the author of a new book that re-mystifies the famous artist.

Verity Babbs

Leonardo da Vinci is one of the most famous artists of all time, a household name even for total art novices and with more than 10 million people flocking to see his masterpiece, the Mona Lisa, in the Louvre each year. We know about his rivalry with contemporary artist Michelangelo, we’ve heard about his complex inventions, and we’re aware of his proclivity for writing backwards. But who was he?

An upcoming book by art historian Stephen J. Campbell, Da Vinci: An Untraceable Life, digs into what we know—and what we never can know—about the Renaissance genius. In the book, Campbell “addresses the ethical stakes involved in studying past lives” and demonstrates that “it is in the gaps and contradictions of what we know of Leonardo’s life that a less familiar and far more historically significant figure appears.”

Da Vinci: An Untraceable Life is being released by Princeton University Press on February 4, 2025; it will be Campbell’s tenth book since 1994, and his ninth focused on the history of the Italian Renaissance.

We spoke to the author about this “anti-biography,” what makes Leonardo so “untraceable,” and what made him want to dig deeper into the artist.

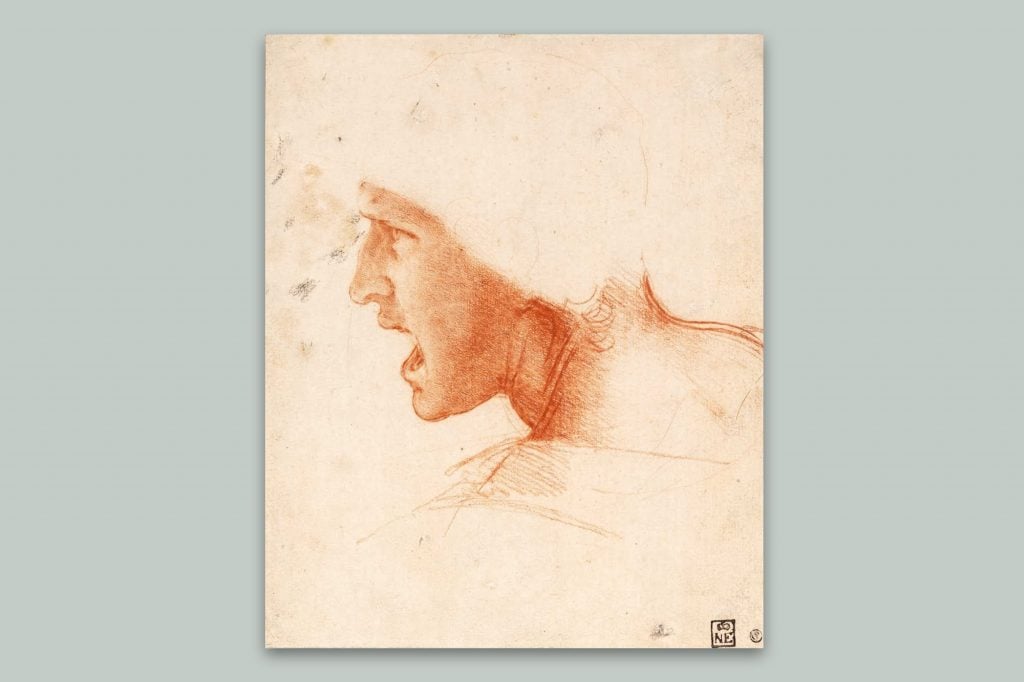

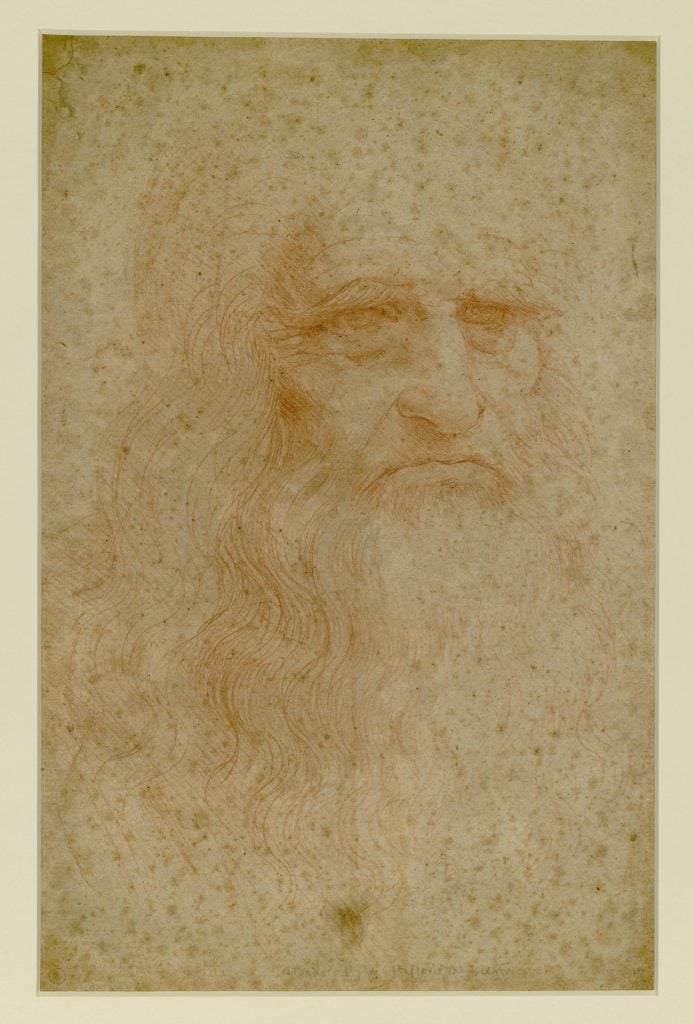

Leonardo da Vinci, Portrait of an Elderly Man. Ca. 1500-05. Image courtesy of Princeton University Press. HIP / Art Resource, NY.

Despite being one of the world’s most famous artists, you call Leonardo’s story an “untraceable life.” Tell us a little about that.

I was thinking of the poet and critic Paul Valéry’s 1894 essay on Leonardo. He stressed that we know a great deal about Leonardo’s thought, from the large quantity of notebooks and drawings, but that these are “visible fragments of a personality completely vanished, leaving us equally convinced both of his thinking existence and of the impossibility of ever knowing it better.” Two years later, an Italian historian published documents indicating that as a young man Leonardo had been prosecuted for sodomy, and then acquitted. For Sigmund Freud, writing in 1910, that one detail was the master key that unlocked Leonardo’s psychic and emotional life, his entire personality. Leonardo’s genius, and the ambiguous allure of his paintings, were symptomatic traces of a repressed or sublimated homosexuality. Our entire modern construction of Leonardo stems from Freud’s psychologizing approach.

And yet, there was nothing unusual about being prosecuted for sodomy in 15th-century Florence—three out of five men under 30 were so charged. And that prosecution is one of the very few biographical facts that come down to us about Leonardo in the first 30 years of his life. Yet somehow, an entire industry of Leonardo biographers have convinced us that we know more, that Leonardo is as familiar as a contemporary celebrity.

There are long stretches of years for which we have little or no information—his apprenticeship in Florence and its aftermath during the 1470s; his early activity in Milan in the 1480s. While his famous projects from the 1490s and 1500s—The Last Supper, the great bronze horse for the rulers of Milan, the Mona Lisa—have left traces in the archives and in eye-witness accounts—we still know very little about how Leonardo lived, his comings and goings, his intimate circle and emotional connections. Such gaps are not surprising in the record of a pre-modern artist. His notes and drawings fill thousands of pages, yet apart from the briefest of glimpses—recording the death of his parents, for instance—he says next to nothing about himself. The earliest brief biography from the 1520s mainly lists his accomplishments (and non-accomplishments), and the “lives” that come after are full of errors, prejudices, and inconsistencies.

You also call this book an “anti-biography.” Why?

There’s a general perception, typical of nearly all the biographies of Leonardo from the past two decades (and there are many of them), that we know the intimate details of the artist’s life, that we can plot the psychological impact of life events and turbulent historical events that he witnessed. The tantalizing fragments are embroidered to fit the psychology of a personality we can recognize: a ‘creative,’ a tech innovator, a flamboyant and gregarious gay man, a pacifist, even a sufferer from ADHD.

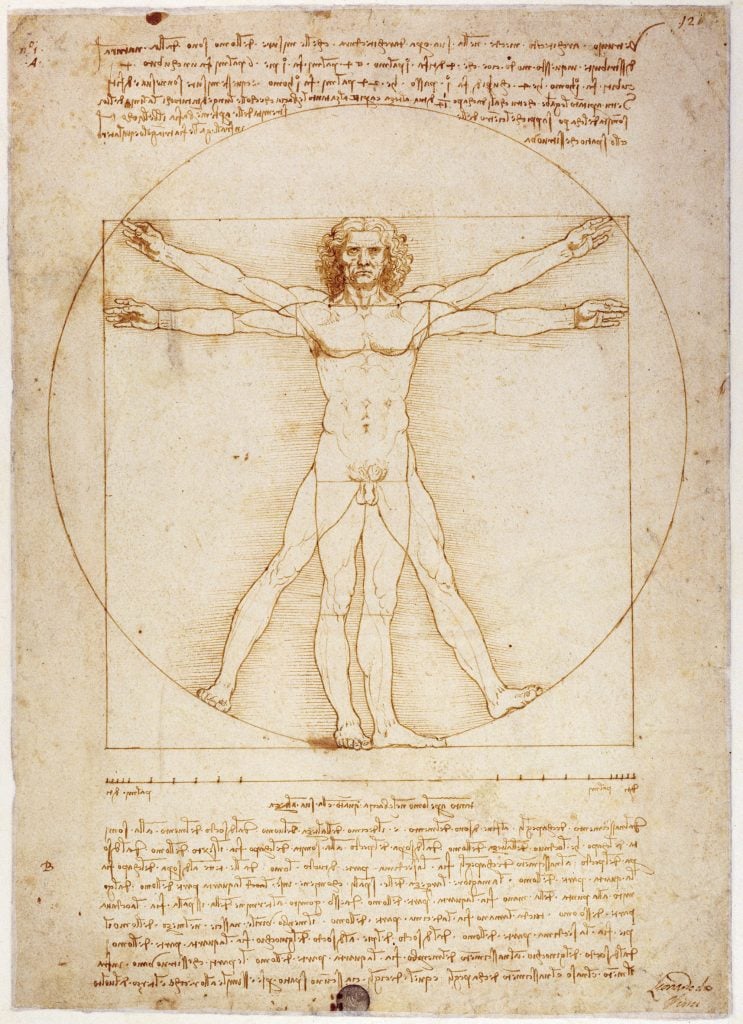

The more that Leonardo fails to cohere as a biographical subject, the greater the modern obsession with finding not just portraits—we have no certain self-portraits of Leonardo, although there have been many claims to identify one—but physical traces: his fingerprints, his DNA, even the bones of his relatives. I wanted to disrupt that illusion of a familiar Leonardo, and restore a sense of strangeness, which is to say, how he belongs to a time in so many ways not like our own. The gaps in his life point the way to a larger historical understanding of the world of pre-modern artisans—how, by experimenting not just with raw materials and media, but with metallurgy, chemistry, and optical theory, makers of things became makers of knowledge.

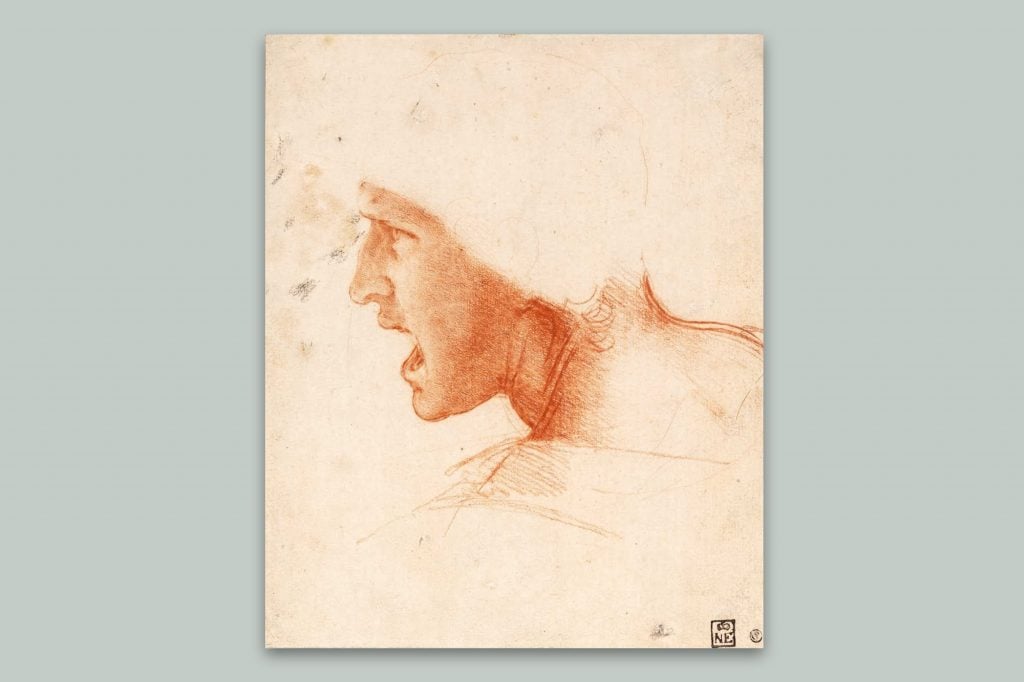

Leonardo da Vinci, Study for the Battle of Anghiari. Image courtesy of Princeton University Press. © The Museum of Fine Arts Budapest/Scala / Art Resource, NY,

What drew you to Leonardo?

I never thought I would write about Leonardo. I wasn’t even especially interested in Florence, since I was drawn to less well-known artists working in places like Padua, Mantua, Ferrara, Brescia, and Bergamo. And yet as I studied work by Leonardo’s contemporaries in these other centers, I found evidence of artistic dialogue and the exchange of ideas. Long ago I tried to show that Leonardo was aware of the work of the Ferrarese court artist Cosmè Tura. More recently, I became really interested in how younger painters in both Milan and Florence responded to Leonardo, how they made sense of his radical pictorial experiments, and how their responses were often far from complacent. Sometimes, there are signs of resistance. In the book, I look in particular at the Lombard Gaudenzio Ferrari, and the Florentines Andrea del Sarto, Rosso, and Jacone, and how they made sense of Leonardo’s work.

What made you want to write this book?

I wanted to write a book that would create conversations, and that would consider Leonardo as an open set of questions, rather than a solved problem. A book that would inspire curiosity in a college classroom, as well as for non-specialist readers. In the last ten years, the media noise around “Da Vinci” has become hard to ignore if you study the Italian Renaissance: dodgy attributions, new versions of the Mona Lisa coming out of the woodwork, new crazy theories about the identity of the Mona Lisa, for instance, or allegations that the Salvator Mundi—a painting that Leonardo was certainly involved with—is a “fake.” And heritage media were giving a platform to quite ridiculous claims, especially if it could be alleged that “scientists” had solved a da Vinci “mystery.”

My colleagues and students were constantly asking me about all of this, so I wrote the book in part to dispel the da Vinci noise, and in part because I wanted to understand the whole phenomenon. What does our da Vinci cult tell us about ourselves, in the 21st century? It certainly indicates that we’ve come to regard tech innovation and tech entrepreneurism as the ultimate cultural achievement of our time, and “da Vinci” has come to serve a branding function.

Leonardo da Vinci, The Vitruvian Man. c. 1490. Image courtesy of Princeton University Press. Cameraphoto Arte, Venice / Art Resource, NY.

How has writing Untraceable differed from the experience of writing your other books?

The bibliography! There’s so much to read about Leonardo. Too much, in fact. Every time I made a claim in the writing, I had to make a deep dive into the scholarly literature to see who, if anyone, had said it before. The fact that much of the book was written during pandemic lockdown made the source checking all the more challenging. And it’s never been the case before that an artist I am writing about is so frequently in the news—it can be a struggle to keep up.

Did you learn any surprising facts during the research for this book that you hadn’t expected?

The facts have all largely been known since mid-20th century, and while new facts sometimes come to light—for instance, a brief note by a contemporary who records Leonardo working on the Mona Lisa in 1503—it’s not clear how they change our understanding of the artist. What matters is how we connect the bare facts to each other, and what stories we tell with them.

I make no claim to discover new drawings or documents. I believe that I offer historical insights about artisans who wrote in Renaissance Italy, and above all about the nature of life writing by artisans. This takes us into considerations of what personhood meant in the pre-modern world, the relation between individual and group identity – especially for artists who shared workshops and collaborated on works. While Leonardo is in many ways a singular phenomenon, it’s important also to understand what is typical about him. Renaissance individualism, a 19th-century idea, is a much-overvalued concept.