Art World

Leonardo da Vinci Made a Secret Copy of ‘The Last Supper’ and, Miraculously, It Still Exists

A new documentary tracks down the second version of Leonardo's masterpiece.

A new documentary tracks down the second version of Leonardo's masterpiece.

Sarah Cascone

Turns out The Last Supper had a second course. A near-pristine copy of Leonardo da Vinci’s iconic painting—created by the Renaissance master and his studio—is offering a glimpse into what one of the world’s most famous artworks looked like when it was new.

The Last Supper is simultaneously one of art history’s greatest triumphs and biggest tragedies: The towering artist captured the emotional and dramatic intensity of one of the most important episodes from the Gospels, but he was so committed to outdoing the typical cenacolo fresco that he chose an untested medium, using oil paint that failed to bind with the underlying plaster and began decaying within years of its initial application.

The centuries have not been kind to the masterpiece—only 20 percent of the original painting is thought to remain intact, making it difficult to fully comprehend the impact the piece would have had when it was new. But what if there was a way to turn back time, to return to Leonardo’s studio, if you will, and see The Last Supper as he did?

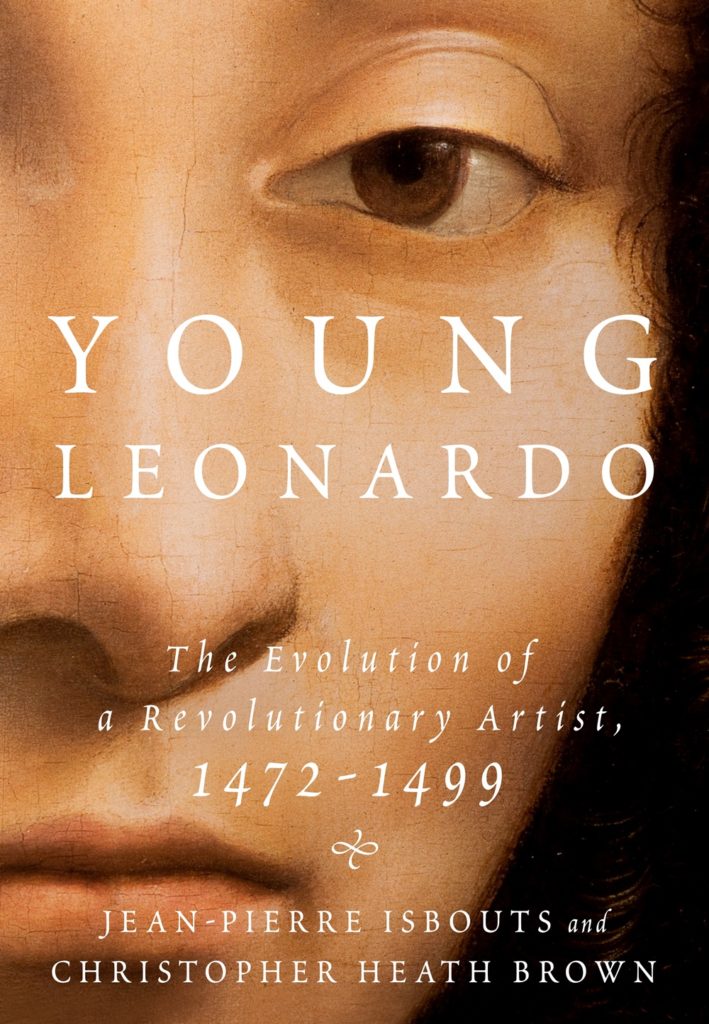

When authors Jean-Pierre Isbouts and Christopher Heath Brown were working on their 2017 book The Young Leonardo: The Evolution of a Revolutionary Artist, 1472–1499, which follows the Renaissance great from his career beginnings in Florence to his major breakthrough, The Last Supper, they assumed such a miracle was impossible.

Then, one day at a party, a friend told them that there was a second version of the painting, completed by Leonardo and his studio on canvas just a few years after the original mural. “I said ‘you’re crazy!'” Brown told artnet News at a recent screening of the pair’s new documentary short, The Search for the Last Supper, at New York’s Sheen Center for Thought and Culture. The film tracks the origins of this little-known second version and the authors’ efforts to trace it to a remote abbey in Tongerlo, Belgium, an hour outside Antwerp.

Young Leonardo: The Evolution of a Revolutionary Artist, 1472–1499 by Jean-Pierre Isbouts and Christopher Heath Brown (2017). Courtesy of Thomas Dunne Books / St. Martin’s Press.

When they finally found the second painting, they were amazed to discover just how good the Tongerlo Last Supper looked. The figures line up perfectly, suggesting it was made using the same cartoons used to produce the original. “When we went to overlay them, we had no idea they were going to be such a perfect match,” said Isbouts. The film shows how the work on canvas fills in the gaps in the famed fresco, seemingly completing the painting.

The completion of The Last Supper marked the end of the first stage of Leonardo’s career, the fulfillment of his early promise in the form of a painting immediately recognized for its artistic genius. Among the work’s early admirers, in fact, was King Louis XII of France, who had conquered Milan, and, according to art historian Giorgio Vasari, had taken the time to visit Santa Maria della Grazie.

The king desperately hoped to bring the painting with him to France, which was then severely lacking in arts and culture, “but the fact that it was painted on a wall robbed his Majesty of his desire, and so the picture remained with the Milanese,” wrote Vasari.

According to Brown and Isbouts, the king was nevertheless undeterred. “If he can’t have the fresco itself, he will have the next best thing: a copy on canvas, that he can take back to France,” the documentary explains. The film points to a letter dated to January 1507, tracked down in the archives in Florence, in which the king writes that “we have need of Leonardo da Vinci,” who had an assignment back in his native city.

Based on this evidence, it seems likely that Louis XII commissioned Leonardo and his studio to paint a full-scale copy of The Last Supper, just eight years after they completed the original in 1499. Furthermore, a 1540 inventory of the governor of Milan’s estate in Gaillon, France, includes a “Last Supper on canvas with monumental figures that the king brought over from Milan.”

The poster for The Search for the Last Supper. Courtesy of the Sheen Center.

Brown and Isbouts believe that Andrea Solario, one of Leonardo’s best assistants, was largely responsible for overseeing the work, as he was with other known copies of the artist’s work created by his studio. Solario is known to have been in Milan while Leonardo was completing the original version of The Last Supper, and worked at the Gallion estate beginning in 1507—presumably arriving with the completed copy.

The work was then purchased in 1545 by the abbey in Tongerlo, Belgium—perhaps, the documentary argues, in defiance of Calvinist prohibitions against religious art. At the time, the abbot identified the work as a Leonardo.

Today, Brown and Isbouts have shown the painting to experts who believe some 90 percent of it was done by members of the artist’s studio. The paintings of Jesus Christ and St. John, however, may be by Leonardo himself—unlike the rest of the painting, X-ray analysis shows no underdrawings for these two important figures.

Seeing the long-forgotten copy for the first time “was overwhelming. I was blown away—it’s so vast,” Isbouts said. “The fresco is the fresco and that’s the original painting—but there’s so little you can see! So you need to see Milan, and then you need to see the Tongerlo.”

Leonardo’s studio also produced a third copy in about 1520, led by Giovanni Pietro Rizzoli, or Giampietrino, that now belongs to London’s Royal Academy, but it is not as faithful a replica. “Although it is a copy, it was seen as a real window into the achievements of Milan,” and an educational tool for students, the documentary notes. (Because of renovations to the academy, it is currently hung high on the wall of the Magdalen Chapel at Oxford.)

The documentary, which will air on local PBS stations, aims to inform viewers about the little-known Tongerlo copy and its fidelity to the now-nearly ruined original, but also to help raise funds for the much-needed restoration of the canvas. While it is in good shape compared to the ravaged mural, it endured significant damage during a fire at the abbey in 1929.

“It’s made up of multiple canvases stitched together, and they’re very very delicate,” said Isbouts, who expects the full restoration will cost €500,000 ($616,000). “All the funds will be wired directly to the account of the abbey, who are delighted.”

Watch the trailer for the documentary: