Art History

Who Was Leonora Carrington? The Untold Story of the Mystical Surrealist Whose Visions Shaped the 2022 Venice Biennale

In both her fiction and her art, Carrington predicted some of the major themes that haunt the present.

In both her fiction and her art, Carrington predicted some of the major themes that haunt the present.

Eleanor Heartney

The 1985 publication of Whitney Chadwick’s Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement radically upended art historians’ understanding of surrealism. Though women had been part of the Surrealist entourage since its inception and were included in a number of exhibitions, their role tended to be circumscribed. The movement’s male founders regarded women as natural embodiments of the irrationality that they themselves laboriously strived to cultivate. Idolized as muses, women were sidelined as creators both by the male surrealists and by subsequent art historians. Chadwick’s book changed all that by drawing attention to a raft of fascinating women associated with the Surrealist movement who are now recognized as remarkable innovators in their own right.

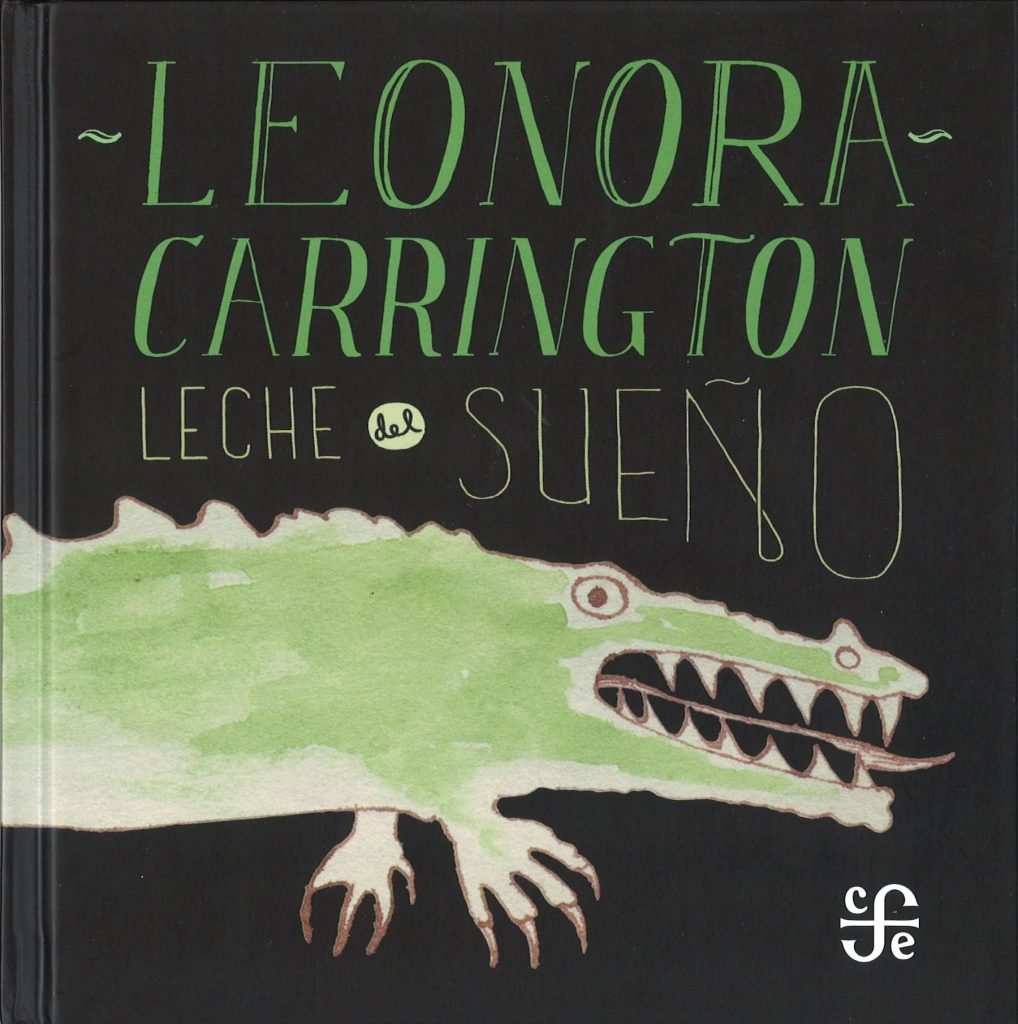

One of these in particular, Leonora Carrington, is having a moment now. Included in the Metropolitan Museum’s recent “Surrealism Beyond Borders”—itself a piece of ground-breaking revisionism—she has for some time been the subject of an academic cottage industry. Now Carrington has inspired both the name and the theme for the upcoming Venice Biennale. Director Cecilia Alemani has titled her edition “The Milk of Dreams” after a truly bizarre illustrated children’s book by Carrington featuring such anomalies as a sofa that swallows vitamins and grows legs and a boy whose head becomes a house.

From this and from Carrington’s prodigious output of paintings, stories, plays, and novels, Alemani has distilled three concepts that will guide the Biennale: “the representation of bodies and their metamorphoses; the relationship between individuals and technologies; the connection between bodies and the Earth.” In other words, very current preoccupations with fluid identities, cyborgs and cybernetics, and ecology.

Cover of Leonora Carrington’s Leche Del Sueño (The Milk of Dreams) (Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2013).

Who was Carrington? Her work brims with dream symbolism, metamorphoses, mythical creatures, ritualistic acts, people morphing into animals, and animals morphing into people. Her egg tempera paintings are the offspring of Bosch and Brueghel by way of Celtic mythology, while her novels and stories evoke Kafka, Buñuel, and Poe. A justly famous early painting, Self Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse) (1938), hints at her continuing appeal. It presents the artist as a wild creature, outfitted in riding breeches and framed by a mass of unruly black hair. She perches tensely on the edge of an upholstered chair alongside a lactating wild hyena. Both look to the viewer with expressions of wary intelligence. Hanging on the wall behind is a giant rocking horse whose posture mimics that of the white horse running free outside an open window.

This painting is a declaration of independence by a young woman who was raised to be a pampered society wife. Carrington was born in 1917 into a wealthy upper class British family. Her childhood home, Crookhey Hall, appears from photographs to be the kind of forbidding drafty manor that would work perfectly as the setting for a Gothic horror story. Carrington was expected by her textile tycoon father to marry well, but the rebellious young woman kept being expelled from Catholic boarding schools. She submitted reluctantly to being presented to the court of Edward V, but insisted on sitting on the sidelines reading a book. She later dramatized her resistance in a story titled The Debutante. The title character escapes her debutante ball by trading places with a ravenous hyena who passes for human by donning the face of the maid whom the animal has just eaten.

Carrington’s parents reluctantly allowed her to study art in London where she met the much older Surrealist artist Max Ernst. He became her ticket to what would prove a hard won freedom. The two artists shared a rich creative life together, first in Paris and then in southern France where they fled to escape his angry wife. Though demanding and paternal, Ernst encouraged Carrington’s interest in the occult and introduced her to a world of surrealist thinking and artists.

Leonora Carrington’s in “Modern Couples: Art, Intimacy and the Avant-garde” at the Barbican Art Gallery. (Photo by John Phillips/Getty Images for Barbican Art Gallery)

One has a sense of the imaginative worlds they shared from their portraits of each other. In Bird Superior: Portrait of Max Ernst (1939) Carrington presents her lover as a Shamanic figure in a feather coat and merman tail who carries a lantern containing a white horse. Another horse, Carrington’s symbol for herself, appears behind him frozen in ice. Interpretations of this work vary—some critics have seen it as a cry against her formidable companion’s stifling presence, while others point out that Ernst resembles the Tarot character of the Hermit, seeker after wisdom. The frigid atmosphere of this painting contrasts sharply with Ernst’s portrait of Carrington, Leonora in the Morning Light (1940). Here the wild haired beauty and her horse avatar are entangled in a lush jungle of vines, suggesting Ernst’s perception of Carrington as an unschooled child of nature, or in his words, a “bride of the wind.”

Their idyll came to an end when the German-born Ernst was interned as a “hostile alien” at the outset of the Second World War. Carrington suffered a nervous breakdown and was involuntarily committed to a Spanish asylum whose horrors continued to haunt her throughout her life. En route to another asylum in South America, she escaped through a bathroom window, married a Mexican friend with diplomatic immunity, and eventually settled in Mexico City. There she divorced, remarried and became part of an expat group of surrealist artists. She lived there, with occasional forays to New York, for seven decades. She died in 2011 at the age of 94, one of the last of the original surrealists.

A view inside British-Mexican artist Leonora Carrington’s house and studio in Mexico City, on May 24, 2021. Photo: Claudio Cruz/AFP via Getty Images.

After her split from Ernst, Carrington’s closest intellectual comrades were women. Leonor Fini was a stalwart supporter during the dark days when Carrington was descending into madness. Later, in Mexico City, Remedios Varo was her fellow explorer into the realms of alchemy, the occult, and the Celtic mythology that Carrington’s Irish mother and nanny had instilled in her as a child. These influences can all be seen in Carrington’s pivotal 1947 work The Giantess (The Guardian of the Egg). This haunting painting presents a colossal figure set in a Brueghel-like landscape populated by tiny figures and marine images. The Giantess’s enormous body is shrouded in a white cape from which a flock of geese escape. It is topped with a tiny innocent face surrounded by a halo of golden wheat. The title references a pair of tiny hands that emerge from the cape and delicately shelter a small egg.

Possible readings of this painting are myriad. The egg, a recurring Carrington motif, suggests at once fertility, new life, and the egg-shaped vessels in which alchemists transmuted elements. The birds are emblems of freedom and migration. The Giantess herself evokes Robert Graves’s White Goddess. Carrington described this book about mythology and poetry in pre-Christian nature-based matriarchies as “the greatest revelation of my life.” The painting suggests a paean to female power, alchemical mutability, and the worship of nature.

Leonora Carrington’s The Giantess by Leonora Carrington during the media preview May 26, 2009 at the Christie’s Latin American Sale in New York. (Photo by Timothy A. Clary/AFP via Getty Images)

These were themes that Carrington continued to explore throughout the rest of her long career. Critics have invoked any number of esoteric systems to decipher the mysterious iconography in her work, including Celtic mythology, astrology, tarot, Jungian archetypes, and indigenous Mexican folk traditions. But in all cases Carrington put her own spin on these symbols, infusing them with a sense of feminine magic. Her paintings and writings ground the marvelous in women’s everyday life. Many works are set in kitchens, bedrooms, and gardens. For Carrington, art and cooking both represented forms of alchemical transmutation. For example, a painting from 1975 titled Grandmother Moorhead’s Aromatic Kitchen is anything but a simple cooking demonstration. Three hooded crones cluster around a table laden with mysterious herbs and plants in the company of a giant goose and a horned goat. Other masked figures on the periphery engage in mysterious cooking-like rituals. Giant heads of garlic scattered within a magic circle double as spices and ingredients in protective spells.

As this painting suggests, in Carrington’s work, women are sorceresses who must shield their magical powers from male interference. The Hearing Trumpet, her one full-length novel, also interweaves the magical and the everyday and concludes with a post-apocalyptic feminist utopia in which the heroine is reborn by being boiled in a cauldron. She and other survivors of a nuclear holocaust then seek the Goddess who has abandoned earth, noting, “If the planet is to survive with organic life she must be induced to return, so that good will and love can once more prevail in the world.”

All of which suggests why Alemani finds Carrington so relevant to contemporary dilemmas. Carrington embraced her kinship with the non-human world, rejected narrowly materialist definitions of knowledge, and already in the 1970s was sounding alarms about the fragility of the planet. And while other female surrealists were uncomfortable with the feminist label, she embraced it. Carrington famously remarked, “Most of us, I hope are now aware that a woman should not have to demand Rights. The Rights were there from the beginning; they must be Taken Back Again, including the mysteries which were ours and which were violated, stolen, or destroyed.”

A view of the Leonora Carrington exhibition “Fantastische Frauen” at Kunsthalle Schirn on February 12, 2020 in Frankfurt am Main, Germany.(Photo by Hans-Georg Roth/Corbis via Getty Images)

Explorations of pre-historic matriarchal societies and Goddess mythologies were rampant among feminist artists of the 1970s as they sought alternatives to patriarchal genealogies of humankind. But feminist artists from later generations quashed such ideas, deeming them “essentialist” and ahistorical. They worried that a focus on women as healers, herbalists, and magicians came dangerously close to confirming the long-standing western dualism that assigned women to the realm of nature and men to the realm of culture.

Outside the art world, however, interest in such alternate cosmologies found a home in some quarters of science. The Gaia Hypothesis, first articulated in 1972 by chemist James Lovelock and microbiologist Lynn Margulis, takes its name from Gaia, the Greek Goddess who personifies the earth. Lovelock and Margulis propose that we regard the earth and its inhabitants not as separate entities, but as a single self-regulating system. In their scenario, organisms co-evolve with their environment. Using Gaia as a metaphor for a world that is entangled, interconnected, and interdependent, they refuse to separate the human from non-human, organic from inorganic, and species from other species.

Theorist Donna Haraway has extended the Gaian idea to the social sphere. She denounces binary thinking in favor of what she terms a post-human reality. This she describes as a complex system in which there are no firm boundaries between humans and animals or between human and machines. Such ideas echo recent developments in biology, evolutionary theory, genetics, and cybernetics that have undermined firm demarcations between genders, species, and human and artificial forms of intelligence. With her human/animal hybrids, magician priestesses and enchanted landscapes, Carrington helps us visualize such a reality.

Carrington’s son Gabriel Wiesz Carrington is the keeper of his mother’s legacy and has written extensively on her life. He suggests that we might think of her works as navigational tools with which to chart different imaginative possibilities. He has said, “To forget the incredible ability of mental play is to die in a world that is increasingly difficult to inhabit, where false imagination has become a disease, the kind of imagining that only exists as a commodity, a lifeless nothing that pretends to be something we need…” Carrington encourages us to dream, and in dreaming, perhaps, to bring a new world into being.