Artnet Auctions

Artnet Auctions Traces the History of LGBTQ+ Symbols Across the Decades

Junior Specialist Solomon Bass discusses the symbols and meanings of five works in Artnet Auctions' Queer Legacy sale.

Junior Specialist Solomon Bass discusses the symbols and meanings of five works in Artnet Auctions' Queer Legacy sale.

Artnet Auctions

Artnet Auctions’ Junior Specialist Solomon Bass discusses some of the LGBTQ+ symbols historicized in our latest Queer Legacy Auction.

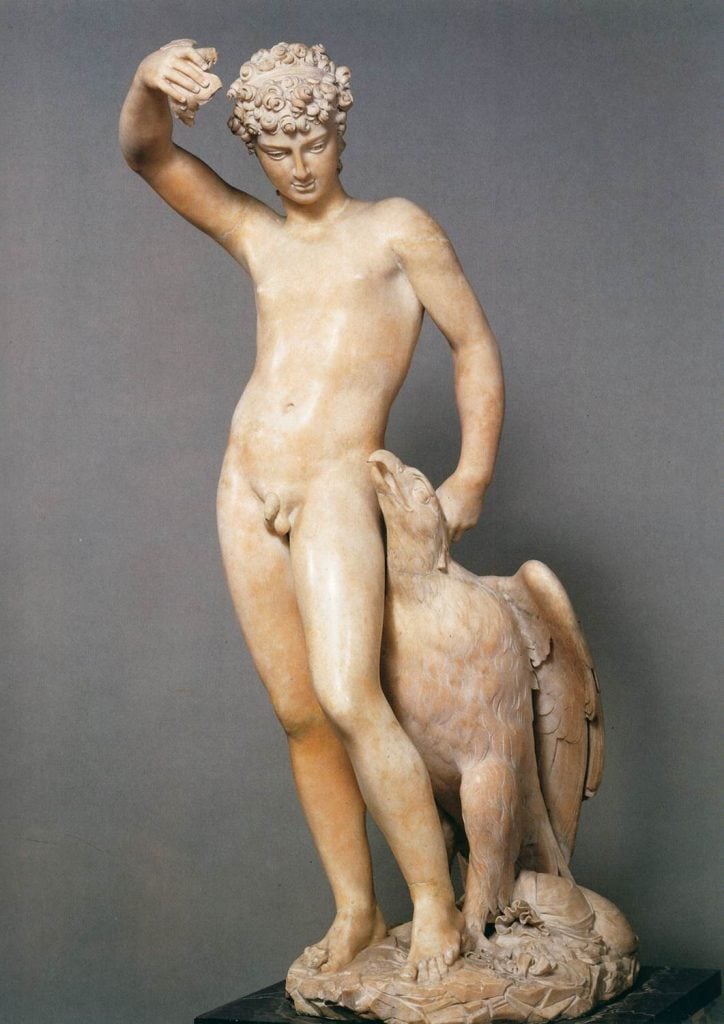

During the 1500s Florence had a reputation as the “Sodom City,” an epithet embodied perhaps most dramatically by the life of sculptor Benvenuto Cellini. Cellini was first convicted for his homosexual acts in 1523—his legal persecutions, however, contrasted with the remarkable creative freedoms he enjoyed, and his work set a tone in queer art history that would endure for some 500 years. Held in Florence’s Bargello Museum, Cellini’s 1540s carved stone figure of Ganymede exemplifies his influence; Ganymede, the young prince of Troy who was carried off by Zeus, was viewed as religiously sanctioned homosexuality. In his sculpture, Cellini incorporated this myth into a nuanced, politicized rebellion.

Symbols of queer art history, such as Ganymede, endured and expanded into the 20th- and 21st-centuries. Artnet Auctions’ second iteration of Queer Legacy traces how visual symbols through decades have remained invaluable in the landscape of LGBTQ+ identity expression.

Joseph Christian Leyendecker, Easter (Saturday Evening Post Cover April 19, 1930) (1930). Live now in Artnet Auctions’ Queer Legacy sale.

Artworks from the 1920s, the age of the Roaring Twenties and the Great Depression, often straddled a fine line between romantic historicism and covert communication when it came to queer encoding. German-American illustrator Joseph Christian Leyendecker’s illustrations are a perfect example. Easter (Saturday Evening Post Cover April 19, 1930) heroically wraps Leyendecker’s own real-life love story with Charles Beach (his model for the work) within a dreamlike space, distinct from the realities of their time. The work’s pastel color scheme and monarchical iconography homoerotically reimagined a Louis XIV-type figure. With this work, Leyendecker pulls fringe culture into the mainstream celebration of an international, Christian holiday. Leyendecker’s prominent placement of a fleur-de-lis, the traditional symbol of French purity, on the pedestal in the painting likewise calls to mind Alexandre Dumas’s 1844 Three Musketeers — in that book, the fleur-de-lis symbol branded criminals; a sobering reminder that homosexuality was then still largely outlawed.

Larry Rivers, Portrait of John Porter (1953). Live now in Artnet Auctions’ Queer Legacy sale.

After the collective and highly gendered trauma of World War II, postwar America underwent a period of concentrated homophobia, grounded in lingering glorification of “machismo” values. While Abstract Expressionism emphasized masculinity through non-figurative brush and splatter work, others of that generation developed and dreamed apart in New York. Larry Rivers, most sensitively, translated the spirit of male writers into a single amalgamate in Portrait of John Porter (1953.) Likely a visual portmanteau of John Ashbery, who was gay, and Fairfield Porter, who had intense male friendships, the drawing codes Ashbery’s openly known queerness above a literal shadow of Porter’s “fitting in.” Frank O’Hara, Larry River’s former lover, wrote a poem entitled Homosexuality one year after Rivers executed this piece, which reads: “So we are taking off our masks, are we, and keeping/ our mouths shut? as if we’d been pierced by a glance!” The tension is tangible here.

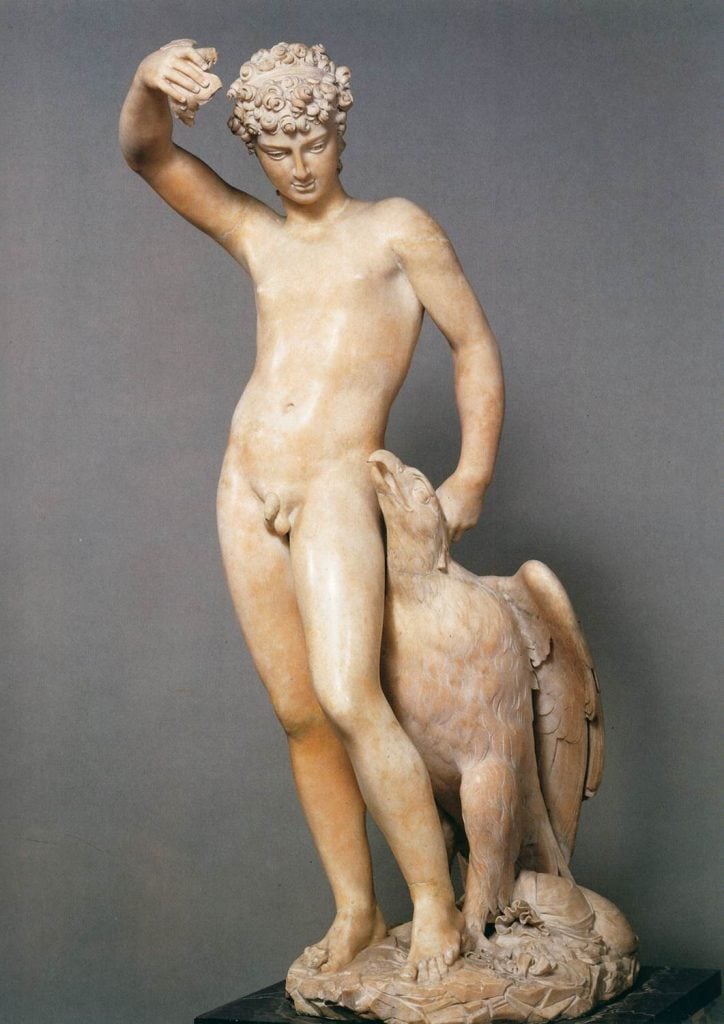

Andy Warhol, Isabelle Adjani (circa 1986). Live now in Artnet Auctions’ Queer Legacy sale.

Less than two decades after the Gay Liberation movement sparked in 1969, the outbreak of AIDS required new forms of activism and heroism. Created at a point of ferocious escalation in media panic over the emergent crisis, Andy Warhol’s collage of French actress Isabelle Adjani from the mid-1980s implied political resistance through unprecedented cultural mythology. In 1986, rumors initiated by the gossip publication Aujourd’hui Madame falsely swirled that Adjani had the virus. She subsequently went onto the evening news to announce, “I am not dead.” At this time, the press sought to scapegoat homosexuals, while focusing on so-called “innocent victims:” heterosexuals and children. Warhol’s composition can be seen as an extremely subtle code for the ideas of guilt and innocence, then normally structured around sexuality, though ironically inverted in the case of Adjani.

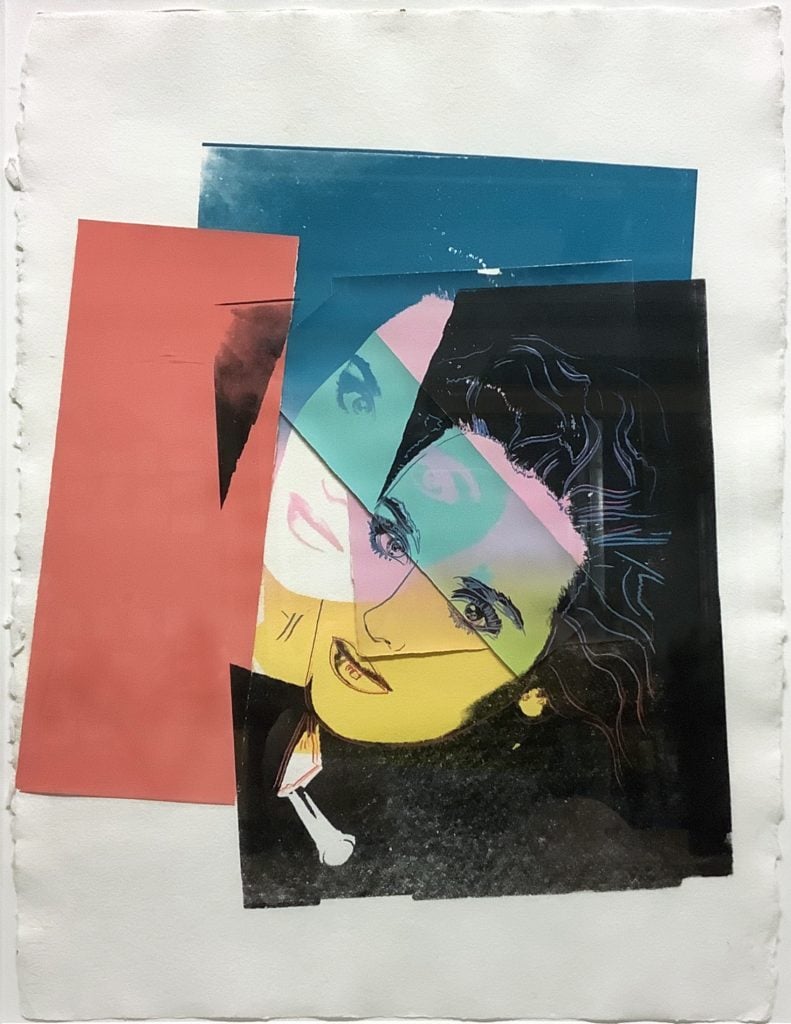

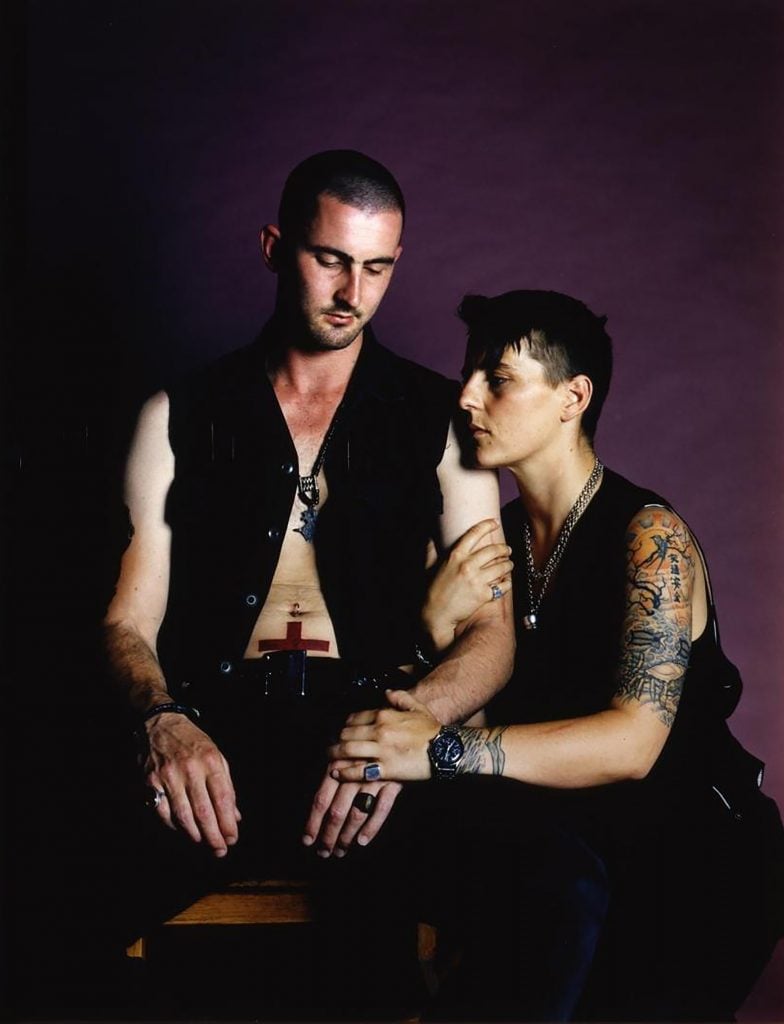

Catherine Opie, Richard and Skeeter (1994). Live now in Artnet Auctions’ Queer Legacy sale.

Catherine Opie’s photograph of Richard and Skeeter (1994), too, commented on themes of culpability surrounding AIDS, which were still persisting when she captured this image. Here, a brother and sister embrace, signaling comfort during a time when deaths from the illness were significantly peaking. Skeeter, at right, owned a San Francisco leather shop, evoking the energy of aspiration and freedom in the 1979 book What Color is Your Handkerchief: A Lesbian S/M Sexuality Reader by Samois (a feminist BDSM organization). Richard, at left, wears a vest that exposes his tattoo of a red cross, a symbol that harkens back to stories like that of Janet Conners, an AIDS activist whose husband died in 1994 after contracting HIV through blood products provided from the Red Cross society. Opie’s intersection of explicit tragedy with freeing mythology harkens back to Cellini’s Ganymede.

SoiL Thornton, Positive Reinforcements, Which Boundaries Do We See, Does Slim Jim Sound Less Sexist Than Slim Jane (2017). Live now in Artnet Auctions’ Queer Legacy sale.

Though queer-coded symbols have been in art since time immemorial, the concepts of sexual and gender difference have only recently launched into the curatorial mainstream. The first major museum exhibition to grapple with these topics came in 2010 with “Hide/Seek, Difference and Desire in American Portraiture” curated by historians Jonathan David Katz and David C. Ward at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington D.C. Bringing to light modern dialectics of expression and repression, that Ganymede initially defined, the exhibition opened paths further for “public articulation” of identity.

SoiL Thornton’s 2017 panel Positive Reinforcements, Which Boundaries Do We See, Does Slim Jim Sound Less Sexist Than Slim Jane correspondingly illustrates the social results of Katz and Ward’s achievement. On its surface of glowing, burnt orange acrylic, thick cords of clay-red yarn run vertically up-and-down, glued to be both straight and squiggling, chromatically evoking the meat stick referenced in SoiL’s title. Throughout the 1990s, Slim Jim was famous for advertisements where World Wrestling Federation Star “Macho Man” Randy Savage wreaked havoc, shouting “Snap into a Slim Jim!” As SoiL personifies, and twists, this national marketing ethos, they question a “tough” and “toxic” narrative, presenting a plane where “Slim Jane” in addition, exists.