People

‘Museums Might in Fact Be Broken’: Cult Art Space Founder Lia Gangitano on Championing Queer Art Outside the Mainstream

The founder of the New York's Participant Inc. wonders why the art world praises shows as "museum-worthy."

The founder of the New York's Participant Inc. wonders why the art world praises shows as "museum-worthy."

Osman Can Yerebakan

New York has had few art nonprofits as dearly beloved as Participant Inc. While predecessors such as Art in General and Exit Art eventually retired, the esteemed Lower East Side institution has only grown stronger in its two decades of programming mainly queer art. And the experimental landmark’s East Houston location has become a kind of unofficial community hub for New York’s avant-garde since it moved to the humble storefront in 2007.

Behind the institution’s cult-like following is founder and director Lia Gangitano, who has unwaveringly championed boundary-pushing art that New York museums still often fail to recognize. Whether photographs of performance artist Ron Athey’s transcendental acts of self-mutilation or the late trans artist Greer Lankton’s poetic dolls, the art on view at Participant’s narrow, dimly-lit space is often provocative. Gangitano, however, operates the space with an ease and compassion that manifests her commitment to a genre of art still deemed too controversial for many larger institutions.

“My career trajectory goes backwards, toward the more alternative and less institutional, but never to a collecting museum or a commercial sector,” she said, as the noise from Participant’s solo show of work by performance artist Keioui Keijaun Thomas filled the space.

With her signature chunky-framed glasses and sleek black hair, Gangitano is an unmistakable fixture in the New York art scene, and one who possesses a unique duality of a bygone DIY sensibility and a transgressive sense of the new. She radiates a calming energy with her careful selection of words.

What many would consider recent directions in art has long come innately to Gangitano. “Many artists are assumed to be just having a moment, but I was working on shows with Lorraine O’Grady, Howardena Pindell, or Lyle Ashton Harris at ICA Boston back in the 1990s.”

While working under an institutional roof, she engaged with organizations fighting against the era’s urgent health crises, including ACT UP and the Women’s Action Coalition. “A whole generation of artists was being wiped out, so remaining outside that political context was not an option.”

“Queer Communion: Ron Athey,” 2021, curated by Amelia Jones, installation view at Participant Inc, New York. Photo: Daniel Kukla.

Gangitano started Participant with a similar commitment to ideals, which, at the time, weren’t necessarily fashionable. Despite the space’s well-known engagement with artists working around various gender representations, its categorization as a queer art space is far from intentional. Gangitano thinks lumping queer artists together under a singular umbrella is a reductive approach to a broad network of philosophies, mediums, and experiences. “The power lies in the fact that it’s not premeditated,” she said. “I have a hard time considering queer art as a monolithic thing.”

For Gangitano, the attachment of “underrepresented” or “overlooked” labels to artists whose careers are seeing delayed recognition makes her wonder whether justice is actually being done to their legacy. Institutions often water down their presentation of artists’ works in order to appeal to broader audiences, she said. “It feels worrisome when the volume is turned down. If the exhibitor mutes the anger in David Wojnarowicz, or the sarcasm in Mark Morrisroe, the intention is not passed on.”

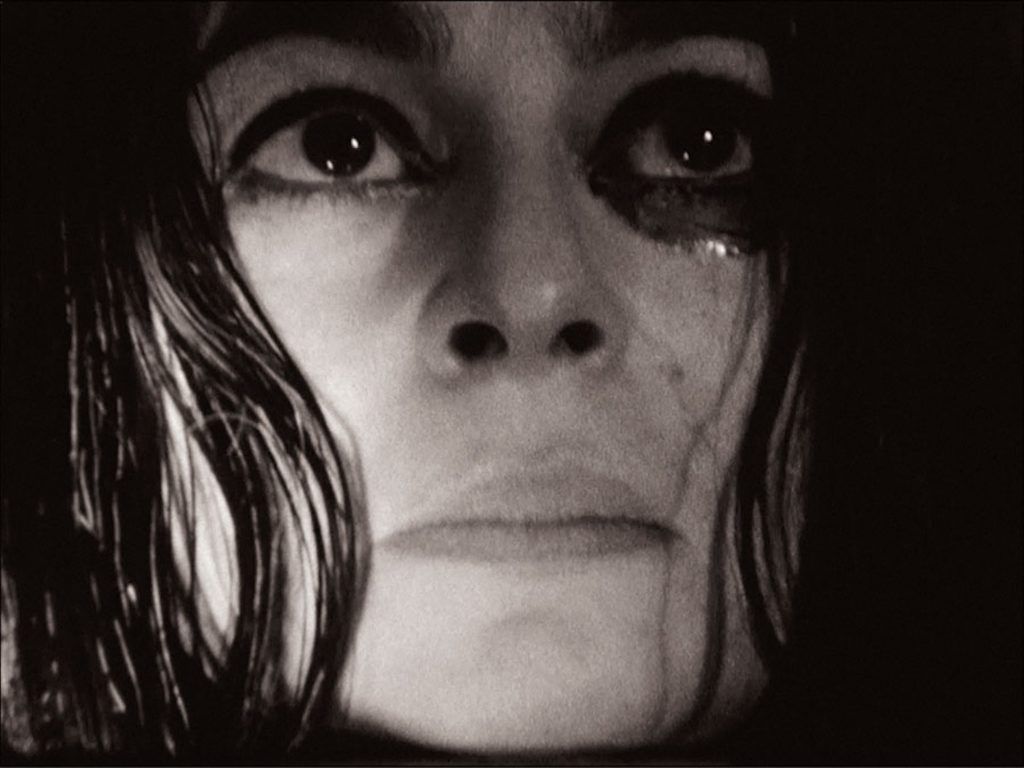

When Ron Athey’s recent survey, “Queer Communion,” premiered at Participant last February, the modestly-sized gallery was brimming with memorabilia, documentation, video, photography, and sculpture dedicated to the L.A.-based performance artist’s three-decade work. But the show, despite Athey’s pioneering status in endurance art, a 456-page publication, and art historian Amelia Jones attached as the curator, initially did not find an originating institution. “I can speculate that this was related to Ron’s work being inherently anti-institutional, or not privileging the institution per se—and that makes no sense,” Gangitano said.

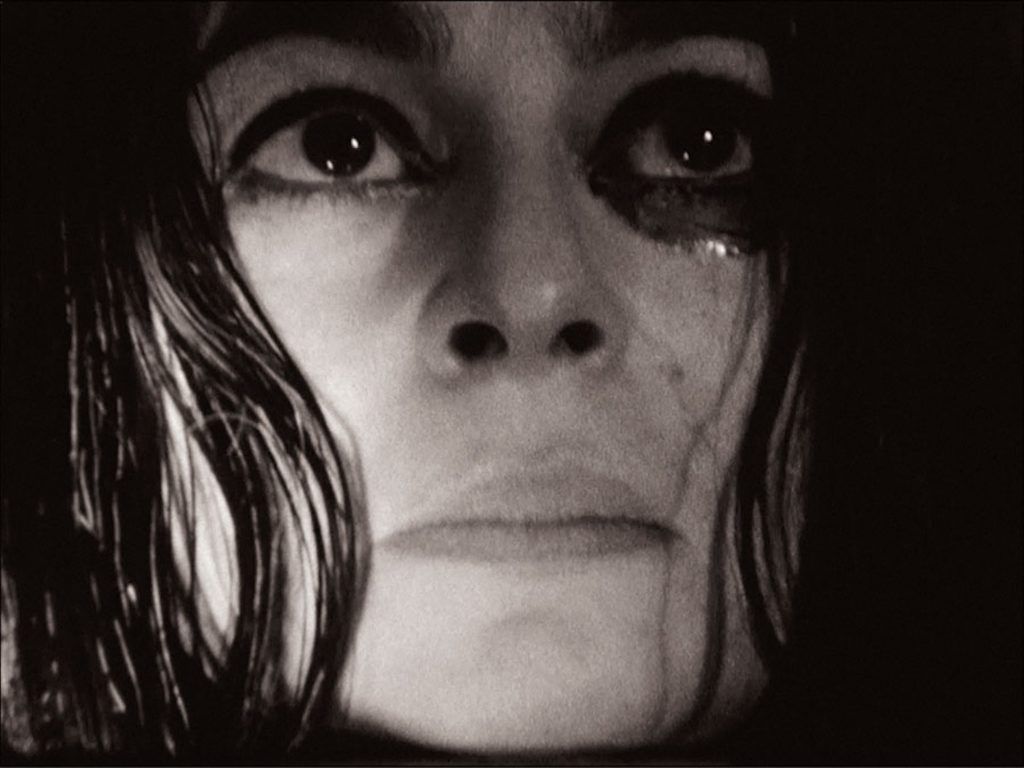

Greer Lankton, LOVE ME (2015), installation view at Participant Inc, New York. Photo: Marti Wilkerson.

Gangitano questions the tendency in the art world to uphold museums as the highest arbiter of acclaim. The overwhelmingly positive response that her Greer Lankton survey, “Love Me,” received in 2014 made her question the classification between alternative institutions and mainstream ones. “I took a pause when I realized that the best compliment for a show could be that it was ‘museum level’—why is that good?” she asked. “Part of my recent thinking agrees that museums might in fact be broken.”

Lankton’s meticulous, years-long work with dolls made her a local star in the East Village of the 1980s. But her work had always remained on a periphery occupied by many other trans artists. “Adjusting a canon to finally include Greer was not the show’s goal,” she said. “Rather, it was to understand why a transgender woman working within the context of the East Village scene didn’t fit that generational lifestyle.”

Participant operates on an annual budget of $350,000 and has a 17-member board, predominantly composed of artists. Berlin-based American artist Vaginal Davis recently became its president, while artists Jeffrey Gibson, Justin Vivian Bond, and Derrick Adams have newly joined its ranks.

Although the past year was precarious for Participant, and many other arts organizations of its size, it also had some advantages. “Organizations with modest infrastructures are better equipped with working around small budgets—vulnerability is in our daily existence,” Gangitano said, noting that it was inspiring to watch her grassroots art community turn to mutual aid campaigns and collective organizing in response to both the pandemic and social injustice.

But for now, Participant’s famously packed performances and talks are currently memories of the past. “For the first time in 14 years, the human presence was cleansed and even the ghosts in the basement are gone,” she said. With live performance suddenly shut down, she turned to the digital realm, including launching the online program Participant After Dark,

She remains determined to lean more heavily on virtual programming in the future, too. “Putting 150 people into this tiny space is no longer the best viewing condition for a performance,” she said. “I look forward to pursuing a hybrid of real audience and livestream to broaden the access.”

And, after 14 years on East Houston, Participant will likely move to another space when the current lease ends next year. Gangitano is exploring neighborhoods around downtown Manhattan for its next phase. Change has been brewing in the future of the organization’s programming, too. “At this point, I want to spend my energy to support other curators and artists,” she said. “I am not that compelled to put forward a curatorial platform that is primary mine.”