Up Next

How Libasse Ka’s Painting Career Was Sparked by an Unlikely Meeting in an Electronics Shop

The artist known for his carefully layered paintings is set to have his first institutional solo exhibition at Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens in 2025.

“I believe in the capacity to do things with the tools we have. But my painting is not about freedom,” artist Libasse Ka told me during a recent conversation. “I think freedom is pretentious in a way.”

The 26-year-old Brussels-based artist, who emigrated to Belgium from Senegal in 2010, has forged his career as a painter of layered, shifting abstractions through a spirit of tenacity and invention. He knows how to work within confines. In his hands, painting is not a plaything; it is a mode of survival.

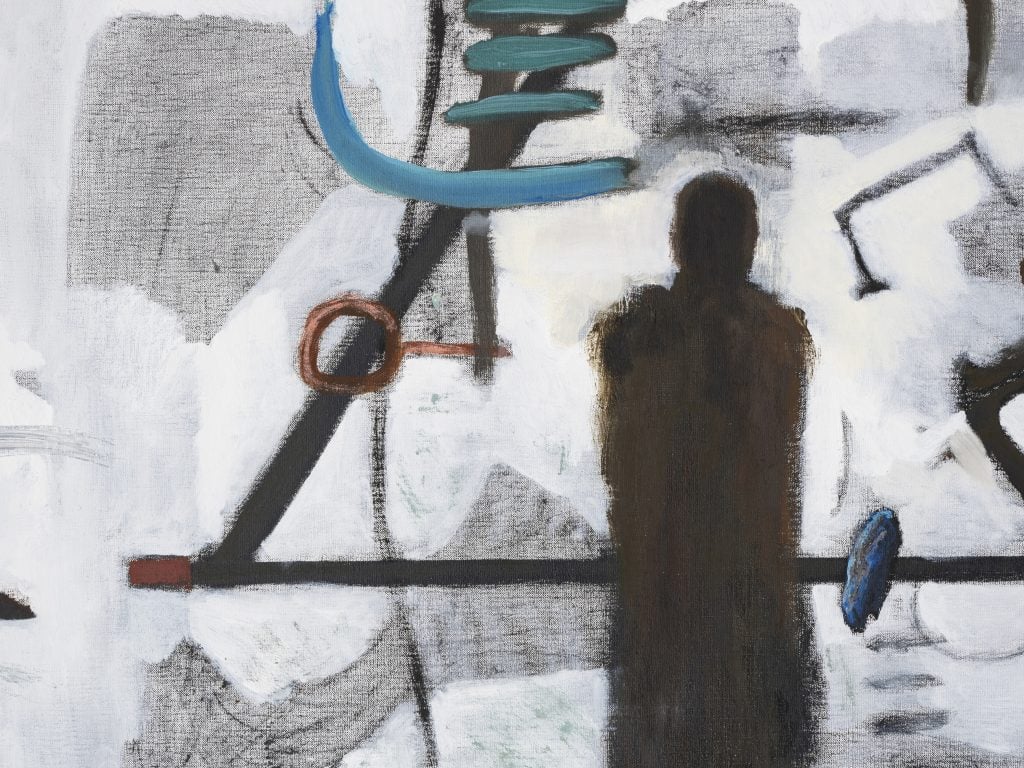

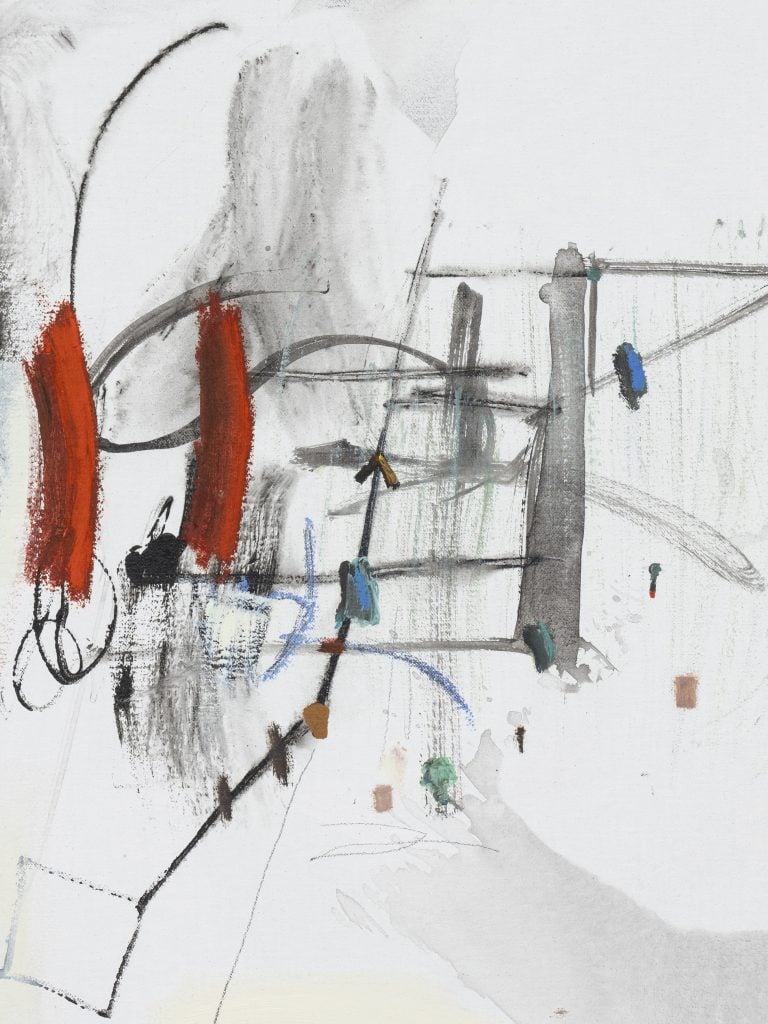

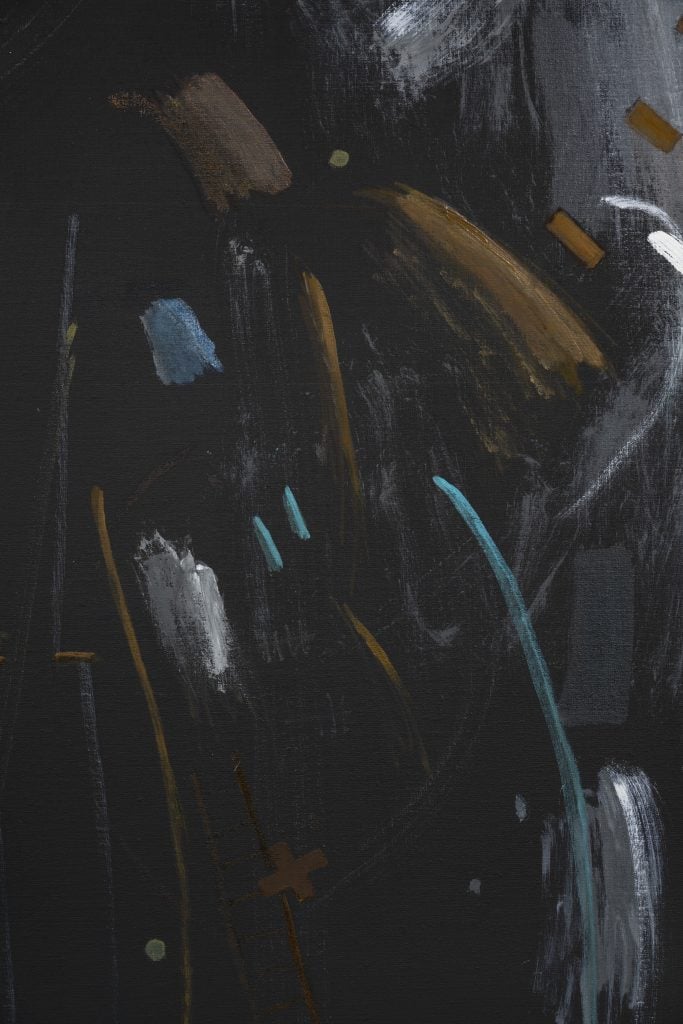

The sincerity and intensity of this approach radiates in his paintings. The surfaces of his canvases, which are often layered oils in pale hues or whites and ivory, hold a panoply of abstract forms and gestures within them. It is a style that has captivated artists, gallerists, and collectors. This October, Ka had a solo presentation at Art Basel Paris with London’s Carlos Ishikawa, which sold out; the booth was a follow-up to Ka’s solo debut with the gallery in January of this year. The Museum Dhondt-Dhaenens (MDD), Belgium will host Ka’s first solo institutional exhibition in 2025.

And while his career is on a steady path, part of Ka’s rise involves a very unlikely chance encounter. And Oscar Murillo.

Libasse Ka, Untitled (2024). © Libasse Ka 2024; courtesy the artist and Carlos/Ishikawa, London; photographer: Damian Griffiths

From Drawings to Oil

After almost a decade focused on making work, Ka is starting to see stability in his career, and with it, his studio and living circumstances. After navigating the headwinds of cultural, professional, and personal expectations, Ka has developed a keen and intuitive sense of self-discipline.

“I cannot control the world, but I can control my eye. Just this little bubble,” he said. “You have to become a tyrant of your own world. I know that as long as I paint, I live. I’ve painted when I’ve been very broke. I’m painting now. No one will take it from me. That’s my treasure.”

Vanessa Carlos, founder of Carlos Ishikawa, came into contact with Ka through the gallery’s star artist Oscar Murillo. The Colombian painter had a chance encounter with Ka, who was working at an electronics store in Brussels as a recent art school graduate. Ka recognized Murillo and introduced himself and Murillo saw some of his drawings he was working on during his shift. “After glancing at his work, Murillo gave him money for a year, no strings attached, to make more of it,” my colleague Kate Brown reported for Artnet earlier this year.

Murillo introduced him to Carlos. At his show at the gallery in February, his work sold for between $7,000 and $38,000.

Libasse Ka, Untitled (2024). © Libasse Ka 2024; courtesy the artist and Carlos/Ishikawa, London; photographer: Damian Griffiths

Yet Ka is also an artist who makes his own luck. Born in Senegal in 1998, Ka moved to Belgium as a child. He painted and drew whenever and wherever he could, taking jobs that wouldn’t tax his ability to focus on his art. “I was always looking for a job that wasn’t that engaging and where I could have time to look up artists on the computer all day long,” he laughed.

He enrolled at Hogeschool Sint-Lukas (LUCA) to study art. “I’ve been drawing my whole life. I used to draw comics till I was 16,” he said. At art school, he became interested in painting. “In the beginning, I was such a shitty painter, to be honest with you,” he said. “It was so hard. Learning oil and the materials. I could not create something like what I had in my head. It was a very frustrating thing.”

Eventually, though, he felt he began to grasp an understanding of light. His enthusiasm for oil paint deepened, too. “Oil has a mystery to it,” he said, of his chosen medium. And he began to ask himself questions.

“How can I get deepness in this work? How can I get the colors to match? How can I get movement? One day an old man said to me, ‘Painting is activating the eye,’” he said. That unlocked new compositional potential for the artist.

Libasse Ka, Untitled (2024). © Libasse Ka 2024; courtesy the artist and Carlos/Ishikawa, London; photographer: Damian Griffiths

In 2021, the artist had his first solo exhibition “The Reality of a Reflection” at Brussels’ Wetsi Art Gallery, curated by Luk Lambrecht (the gallery space was founded by Anne Wetsi Mpoma in Brussels, as a foothold for artists of African descent in the city). Lambrecht, for his part, was first introduced to Ka’s work by the Flemish painter Jan Van Imschoot, who had discovered Ka’s work on Instagram. The exhibition put Ka on the map within the Belgian capital, and things would grow quickly from there, especially after meeting Murillo.

The artist often works on many canvases at once, usually working on four or five at a time, but sometimes painting up to 20 works simultaneously. “I need a certain space between my actions and my thoughts,” he said of his approach. “I jump from one to another and it gives space between one movement to another, between one color and another color, one language to another,”

Libasse Ka, Untitled (2024). © Libasse Ka 2024; courtesy the artist and Carlos/Ishikawa, London; photographer: Damian Griffiths.

The careful layers of his paintings reveal forms gradually; occasionally a figure, a man who might be a stand-in for the artist, occupies these auric spaces. Right now, Ka is focused on the spirit and reaction that take place within his paintings. He’s working on paintings incorporating a unique printing method made using big pieces of plastic. “I paint on the plastics, and then I transfer it on a canvas and it leaves a trace,” he said. The traces build up from there. “I am trying to kill the pencil for now,” he added.

Though he doesn’t want to be defined by the past, Ka is at once a font of art historical and philosophical knowledge and is aware of how such cultural forces frame understanding of his work. “I like to deem painting as this abstract language that’s open for anyone, but culturally it’s actually closed,” he told Lydia Earthy earlier this year. “In some countries, your social class is your cultural class. In other countries, it’s determined by the money that you have.”

The artist resists categorization of his work, whether via culture or art history, and instead steers the conversations back to what he sees taking place between paint and canvas. “I don’t like dogmas because tomorrow I’m going to discover something and it’s going to bring something new into my work,” he said. “You are not the person of yesterday. No one is.”