Art World

Is the Art World Finally Ready to Embrace Craft?

The Loewe Foundation Craft Prize was awarded this week. The exhibition asks big questions.

In the art world, craft occupies a lower cultural status than art. Certain folks sneer at the category as parochial, lacking in concept, or as is an insult within these circles, purely “decorative.” The Loewe Foundation Craft Prize, a cultural arm of Spanish luxury brand Loewe, seeks to fix that.

Typically hosted by a specialist institution—last year the show was held at the Noguchi Museum in New York—in its seventh year the 30 finalists exhibited at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris. During the interim, there has been increased discourse on the importance craft has taken in contemporary art.

Ferne Jacobs, Origins (2018). Courtesy Loewe Foundation Craft Prize.

In her book, String, Felt, Thread, Elissa Auther locates the emergence of the hierarchy of art and craft to the Renaissance definition of painting and sculpture as liberal arts, opposed to mechanical arts such as leatherworking and bricklaying. This binary absorbed a gendered dimension that was reinforced during the 20th century by influential critics like Clement Greenberg and Gregory Battcock, who would in 1968 crown Robert Morris “the leading sculptor of our day” while deriding the following year the “floppiness and house-wifey dumpiness” of Claire Zeisler’s work.

But in recent years the art/craft divide feels like it’s dissolving, as the art world unpicks an exclusionary Western art historical cannon and reclaims traditionally “feminine” and Indigenous traditions of object making. Sheila Loewe, the foundation’s president, told me that she has certainly noticed an evolution in the mainstream acceptance of craft.

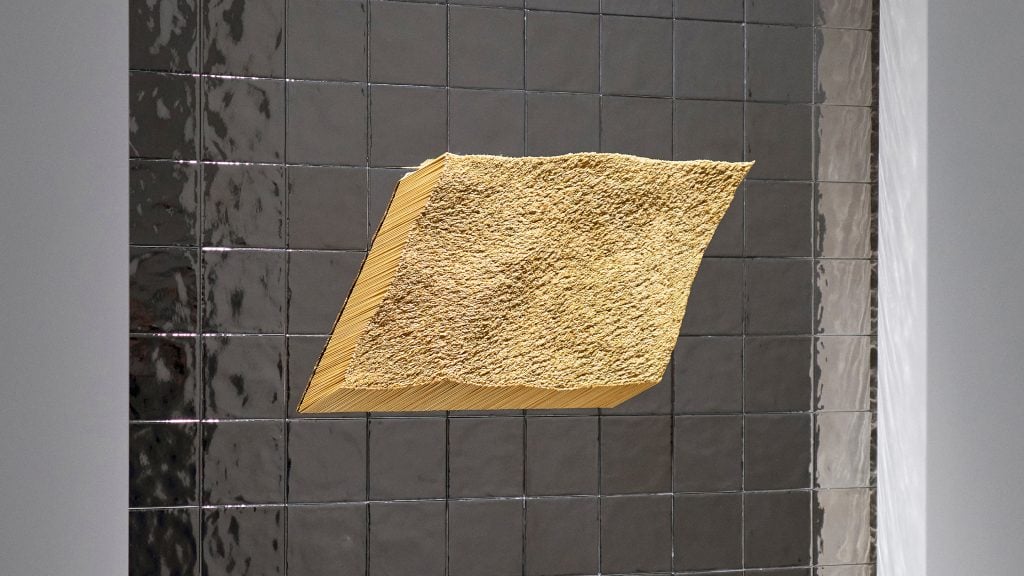

Ikuya Sagara, Reminiscent Wind (2023). Courtesy Loewe Foundation Craft Prize.

“We are happy to show at the Palais de Tokyo, which is the biggest contemporary art museum in Europe,” Loewe told me. “At the beginning of the prize it was more like: art is number one, design is number two, and craft is…somewhere else. You go now to contemporary art fairs all around the world and you see so many textiles, so many crafts being embraced by the art world.”

At this year’s Venice Biennale, a monumental woven strap work referencing Maori birthing mats took home the Golden Lion, meanwhile textiles by Liz Collins, and ceramics by Nedda Guidi and Anna Maria Maiolino were major talking points of the exhibition. In the commercial realm, craft and design are increasingly present at art fairs, as a new generation of buyers opens up to cross-collecting.

Raven Halfmoon, Weeping Willow Women (2023). Courtesy Loewe Foundaton Craft Prize.

Among the 30 finalists in Paris, I was drawn into Japanese master thatcher Ikuya Sagara’s slanted rhombus of rice straw, pampas grass, and wood; an umbilical waxed linen wall hanging by U.S. artist Ferne Jacobs; and Caddo Nation artist Raven Halfmoon’s ceramic Weeping Willow Women dripping in sanguine red glaze and mottled with deep, gestural, finger impressions.

The prize jury gave special mentions to jewelry artist Miki Asai’s chunky wooden rings mounted with diminutive eggshell vases, a non-functional coffee table of loose porcelain bricks by French artist emmanuel boos, and Heecham Kim’s amorphous ash wood vessel inspired by traditional Korean boat-making techniques.

Andrés Anza, I only know what I have seen (2023) Courtesy Loewe Foundation Craft Prize.

The big winner was Andres Anza from Mexico, who will receive the foundation’s €50,000 prize. The honor was announced by celebrity guest Aubrey Plaza in a ceremony studded with Paris fashion royalty including LVMH owner Bernard Arnault, designers Rick Owens and Michèle Lamy, and Louis Vuitton Men’s creative director Pharrell Williams.

Anza’s spiky totemic form comprises thousands of pinched clay protrusions, and draws elements from traditional Michoacan pottery, as well as the history of abstract sculpture.

“I wanted to put Indigenous Mexican craft and art on the same level. I want it to feel nonhierarchical,” Anza told me ahead of his win. “When people see this I want them to be curious and if their first question is: is this craft or is this art? I’m interested in that because I think there should be no line between these things. In the contemporary art world there is always a different space for craft, any sculpture exhibition has a ante-room for ceramics. Why separate them? We should see everything and judge everything alike.”

The jury noted that Anza’s work, “defies time and cultural context, drawing upon ancient, archaeological forms but also tracing a post-digital aesthetic that sees ceramics absorbing the most defining influences of our time.”

Miki Asai, Still Life. Courtesy Loewe Foundaton Craft Prize.

LOEWE creative director Jonathan Anderson, who conceived of the prize in 2016, is a known lover of ceramics and a collector of important masters of the medium like Lucie Rie, Hans Coper, and Magdalene Odundo.

Anderson is glad to see the art world opening up to crafts. “I think it’s quite surprising when I go to institutions now, how you’re seeing a bridging of these things—you’re seeing a Hans Coper with a Giacometti,” Anderson said. “I think there is a kind of leveling. Even if you were to look at the market aspect of it, I would be able to pick up Lucie Rie very inexpensively. Now it is becoming impossible. And Hans—forget it.”

“When I go and see very good contemporary art collections, I’m now seeing an uptick in big collections buying prominent craft people, which was unheard of,” he added.

Anderson credits the shift to a resurgence of research and curatorial interest in craft over the last decade. Yet he acknowledged that there is further to go for his favored medium, despite encouraging signals such as major artists like Sterling Ruby experimenting with the form and the market’s recent reappraisal of Picasso’s ceramic work.

“I think it’ll take a little bit more time. We’re not there yet [with ceramics] but I think in textile art, for example, it has really changed.”

Heechan Kim, #16 (2023). Courtesy Loewe Foundaton Craft Prize.

For all this talk, I am disinclined to overstate the renewed position of craft in contemporary discourse. After all, curators like Mildred Constantine and Jack Lenor Larsen were making efforts to legitimate craft in the 1960s, and subsequent generations of critics and feminist artists like Judy Chicago and the late Faith Ringgold have made significant efforts to move the art world needle. Yet, as Elissa Auther also points out in her book, the aesthetic hierarchy has remained stubbornly hegemonic.

In a cab ride returning from the exhibition, an interior design writer remarked condescendingly that the show was “cute” and I—equally guilty of internalizing this hierarchy—smirked at such a pronouncement coming from an interiors specialist.

Trends in the art market sometimes lead us to believe we’ve come further than we have. Think of the recent vogue for contemporary African painting, and how quickly it has moved on to South American art without sustained engagement. Or the perception that women have reclaimed their place in art history yet the 2022 Burns Halperin Report found that only 11 percent of acquisitions at the 31 U.S. museums the prior year were of work by female-identifying artists.

As much as we may fight it, art world power relations still determine how work is produced, received, and circulated. Which is why despite evolving attitudes towards gender and creativity, the interdisciplinary approaches of contemporary artists, and curatorial prognostication, the entrenched stereotypes about craft persist.

emmanuel boss, Coffee table (Comme un Lego). Courtesy Loewe Foundaton Craft Prize.

We might be closer to healing the art/craft divide than we were in the 1970s. But truly transcending this binary requires a broader sea change in structural and societal attitudes towards gender, labor, and creativity that has yet to materialize.

Even the Craft Prize itself, as it proffers a definition of craft that is rooted in material—”ceramics, jewellery, textiles, woodwork, glass, metalwork, furniture, papercraft and lacquer”—fails to acknowledge that craft is an idea. There is bad art and there is good art, but there is nothing aside from the categorical label that distinguishes objet from oeuvre.

Anderson said he is always trying to answer the question: “how do you show craft in a modern context?” But if the mission of trying to legitimate craft as art implicitly accepts the category of “art,” which subjugates craft, then perhaps what we need is not actually a dedicated craft prize, but a jettisoning of the broken systems of classification in the art world. As generations of critics have now pointed this out, the bricks have been moulded. Now it is time to fire up the kiln.