Art World

Why Are Attendance Rates Nose-Diving at London’s Art Museums? Directors Frantically Search for Answers

“We are seeing a different group of people missing each year,” says one puzzled expert.

“We are seeing a different group of people missing each year,” says one puzzled expert.

Javier Pes

The chairman of the National Portrait Gallery convened an emergency meeting last year with the chairs of eight other museum and galleries in London to discuss an urgent matter. Over the previous years, the city’s vaunted art institutions had been experiencing an unusual decline in visitor numbers—and not by hundreds of thousands, but by millions of people. They were just disappearing. In total, London’s seven biggest art institutions have seen their attendance figures plummet from more than 26 million in 2014 to 24.7 million in 2017.

Revealed in the NPG’s minutes, this dramatic meeting—held by the NPG’s outgoing chair, William Proby—is testament to the challenge facing London’s art institutions and their directors at a moment when museums worldwide are attempting to widen their appeal beyond the traditional cultural tourist and attract digitally engaged millennials.

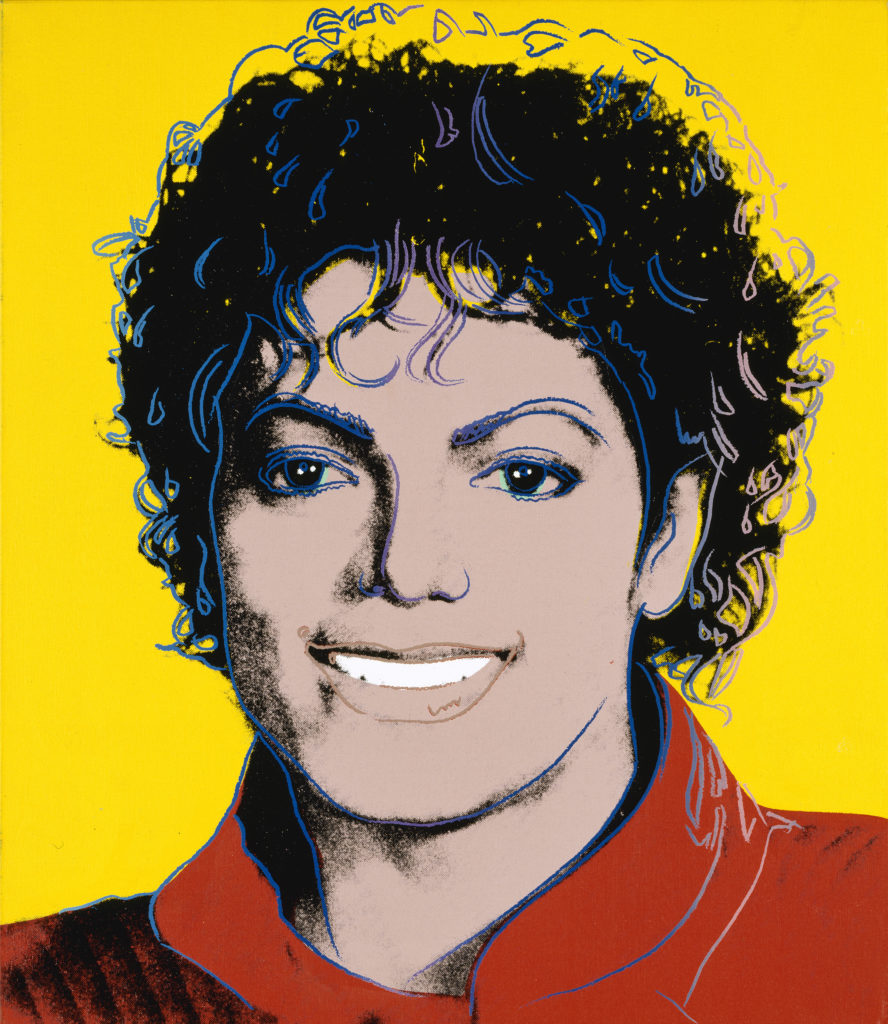

Worryingly, the drop in attendance comes in spite of free entry to permanent collections and a slew of innovative efforts to lure visitors, from to late-night openings and special events—not to mention an embarrassment of exhibition riches that have been marketed to the hilt, including Modigliani at Tate Modern, Delacroix and Michelangelo at the National Gallery, and Scythian gold at the British Museum. The director of the NPG, Nicholas Cullinan, currently has a lot riding on the show he curated of artistic homages to Michael Jackson. The gallery’s attendance has plummeted from more than two million in 2015 to 1.2 million in 2017.

The reasons for a general fall in attendance are unclear. Terrorist attacks in the capital and ongoing transport woes on London’s rail network have been blamed, and this year’s long hot summer will not have helped reverse a trend that is on course to see numbers fall back to around 2012 levels. But artnet News has seen new research undertaken for a group of London museums that suggests the fall may also be due to the end of the “halo effect” of the 2012 London Olympics, which gave the city a massive boost in international tourism.

It is not just tourists who have stayed away, however—Londoners have gone missing, too. The drop in home-grown visitors was particularly dramatic in 2016-17, when researchers found that the fall accounted for 70 percent of the total decline in visits to the capital’s major museums. A spokeswoman for the British Museum confirms that the number of visitors from London and the South East fell in 2016-17. She says that last year they returned, but that visitors from Europe declined.

Andy Warhol, Michael Jackson (1984). Photo: National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C. / Gift of Time magazine © 2018 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by DACS, London.

Statistics collected by the Association of Large Visitor Attractions from its members show that institutions in central London have been particularly affected. The British Museum, National Gallery, and the NPG have seen a combined drop in attendance since 2015 of around 2.4 million visitors, or around 16 percent.

Increased attendance at Tate Modern since its expansion and robust figures from the Victoria and Albert Museum, which last month announced a rise of attendance of nearly a million, have bucked the trend, but not enough to offset a general decline in the city. The capital’s seven biggest art institutions have seen a six percent drop over the past three years.

The director of the National Gallery, Gabriele Finaldi, told his trustees last November that British visitors in particular fell in 2016-17. The minutes of the trustees’ meeting reveal he noted that most central London visitor attractions experienced a decline. A spokeswoman for the NPG says: “The gallery has been working with our neighbors and other museums and galleries in London on research and initiatives to encourage additional visitors.”

Gerri Morris, a founding director of company Morris Hargreaves McIntyre, has been researching visitor trends for the past three decades. MHM reviews the data every six months and works with a group of leading London and international museums so they can compare statistics confidentially. “It’s not surprising people are alarmed at the drop—it has an effect on [institutions’] income and business plans,” Morris tells artnet News. “Paid visits are holding up and many venues have had record-breaking exhibitions, but it is the free visits that are dropping.”

“It perplexes everyone,” she adds, in part because the pattern is complex and falls have not been consistent. “We are seeing a different group of people missing each year. First it was people from the South East, then it was people from London, and now we are seeing drops in European visitors and rest-of-world visits.”

After the sharp fall in visitors from London, that group has “stabilized,” Morris says. “The people who are missing are general tourists and younger backpacker-type tourists, not people who make a beeline for cultural attractions.” People are coming to London, going to Trafalgar Square, maybe seeing Buckingham Palace, but not going into the museums, she explains.

Giuseppe Penone’s Albero folgorato at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Image copyright the artist, courtesy of YSP.

“The Olympics had such a big impact but seven years on, you can’t expect the halo effect to last forever,” Morris notes. But the capital’s loss seems to be the regions’ gain. Attendance is on the rise elsewhere in the UK: the Yorkshire Sculpture Park in the north of England has seen a 39 percent increase in visitor numbers over the past four years.

“We receive half a million visitors a year, but because our galleries are separated by walks, it’s rare to experience claustrophobia or queuing as is the case in London museums—on the contrary, this place is exhilarating,” says Clare Lilley, the director of sculpture park’s program. Unlike its peers in London, where tickets for the biggest shows have edged over the £15 ($20) mark, the Yorkshire Sculpture Park’s temporary exhibitions are free.