Art & Exhibitions

How Hardcore Can Art Get? Does A.I. Need Therapy? And Other Thoughts in the Air at London Gallery Weekend

London's art scene is trying to create a mid-year moment for itself ahead of Art Basel.

London's art scene is trying to create a mid-year moment for itself ahead of Art Basel.

Naomi Rea

The floors were a little sticky at the Groucho, a private members club in Soho that has attracted a louche cohort of creative and media types since the 1980s, and which has had something of a revival in the art scene since it was acquired last year by the hospitality arm of the Swiss gallerists behind Hauser and Wirth. The launch party for London Gallery Weekend was not quite equivalent to the downtown New York scenes snapped by writer and Warhol collaborator Bob Colacello (on view at Thaddaeus Ropac)—but still, a gaggle of beautiful people enjoyed summer spritzes alongside ascendent painters including Sasha Gordon and Joy Labinjo.

For committed patrons of the arts, London’s nascent gallery weekend poses something of an impossible task. The city’s sprawling geography and the 150-odd participating galleries make it infinitely less manageable than its counterpart in say, Berlin. Between exhibitions, opening parties, and dinners, there is perhaps too much competing for your attention.

Joy Labinjo and Precious Adesina attend the Frieze 91 x London Gallery weekend opening party celebrating London’s Creative Scene at The Groucho Club on June 1, 2023 in London, England. (Photo by Dave Benett/Getty Images for London Gallery Weekend x Frieze)

But London needs this. Galleries here have had a tougher time recovering from the pandemic than in other centers. Those difficulties piled on top of the logistical hurdles and bad vibes accompanying Brexit, and even that was before skyrocketing inflation rates and wider uncertainty began to catch up with the art world. With a market that relies strongly on sales made outside of the country, and competition from Paris stealing a lot of the thunder of late, there is a lot riding on this event. It has to excite buyers at home and from abroad, and to create a mid-year moment in the calendar for the city outside of Frieze Week in October.

So what does London’s art landscape have to offer? Here are some questions that were in the air going into the marathon weekend.

Installation view of “To Bend the Ear of the Outer World: Conversations on contemporary abstract painting” at Gagoian in London, open until August 25, 2023. Photo courtesy of Gagosian.

Ever since the rise of abstract painting in the early 20th century, public attention has at intervals tacked back and forth between a love of abstraction and figuration. As of now, in early-mid-2023, trendy figurative painting is enjoying a healthy moment in the spotlight. Yet a behemoth exhibition of 40 living abstract painters at Gagosian raised the question as to whether we are in the midst of a pendulum swing back in the other direction. “I think both have existed in parallel,” curator Gary Garrels told me at the opening of “To Bend the Ear of the Outer World.”

“There has been a lot of public attention in recent years for figurative work and I’ve felt that there’s just as much good, interesting work being made that’s abstract and so wanted to forefront that,” Garrels added.

The exhibition was stuffed with the stars of contemporary abstraction. Even amid stellar works by Gerhard Richter, Cecily Brown, and Frank Bowling, and fare by younger super-stars including Jadé Fadojutimi, you could discover some standout works by artists who have had less airtime of late. Among these were a canvas by Jacqueline Humphries capturing something of the distracting noise of modern life, and a meditative moment of quiet offered by way of Jennie C. Jones.

Installation view, Jacqueline Humphries at Modern Art. Photo by Michael Brzezinski.

There is certainly an appetite for the materiality of abstract painting as we emerge from the pandemic and start returning to events in person. The medium doesn’t offer up easy narrative threads and so its power demands an IRL viewing to take in the scale, color, texture, surface, and gestures being made. But what are the defining characteristics of abstract painting being made today?

“I think it’s about the strength of individuals, the affirmation of individual identity and imagination,” Garrels said. “There’s no slot, no box that everybody’s trying to fit into. There’s no movement. It’s not Abstract Expressionism, it’s not Pop Art, it’s not Color Field… It’s just about individuals having a strength of their own convictions.”

Jacqueline Humphries is also given solo real estate by Modern Art across both its spaces. Her knowing canvases build on the history of abstract painting and infuse it with digitally native forms and gestures. A series of “pre-vandalized” paintings carry marks that recall Jackson Pollock but also understand the political agency of this kind of mark-making today, specifically invoking actions taken by climate activists desperate to capture media attention by flinging substances at paintings in museums. In the catalogue text for the Gagosian show, Humphries reminds us that abstraction is the notion that “maybe you can augment the ‘real’ effect without the intermediary of represented ‘things.’” Her cogent statements applied onto dizzying, staticky surfaces are still flash-burned to my retinas days later.

Installation view, “Hardcore,” Sadie Coles HQ, London, May 25 2023 – August 5 2023. Credit: © The Artist/s. Courtesy of The Artist/s and Sadie Coles HQ, London. Photo: Katie Morrison / Sadie Coles HQ, London.

Many of us have continued to feel the knock-on effects of being physically isolated for several years, and events and openings still don’t totally feel “back to normal.” Over the weekend I witnessed many an awkward dance as people tried to read from micro-expressions whether a handshake or—god forbid!—an air kiss were permitted forms of greeting. Add to that the effects of our mass retreat online and the consequent further disintegration of our shared sense of reality, and many people have come out the other side of lockdown having internalized socio-political isolation that began long before the pandemic and have been polarized on either side of the too-woke and anti-woke divide. So I was on the look-out for themes of physical intimacy, conversations about cancel culture, and any desire for nuance.

And boy did I find them at Sadie Coles HQ. A challenging group exhibition titled “Hardcore,” including 18 artists, explored themes of sexuality in and of itself, wholly indifferent to social rules. As Mistress Rebecca, the dominatrix who wrote the curatorial text for the show, put it: “A hardcore rejects niceties because to be hardcore is to never fall into the safe and simple parameters of right or wrong. Today this seems to be an unnecessarily rare, even brave position to take.”

King Cobra/ Doreen Lynette Garner, In the Feast of the Hogs (2022). ©KING COBRA (documented as Doreen Lynette Garner). Courtesy of The Artist and JTT, New York.

Photo: Katie Morrison / Sadie Coles HQ, London.

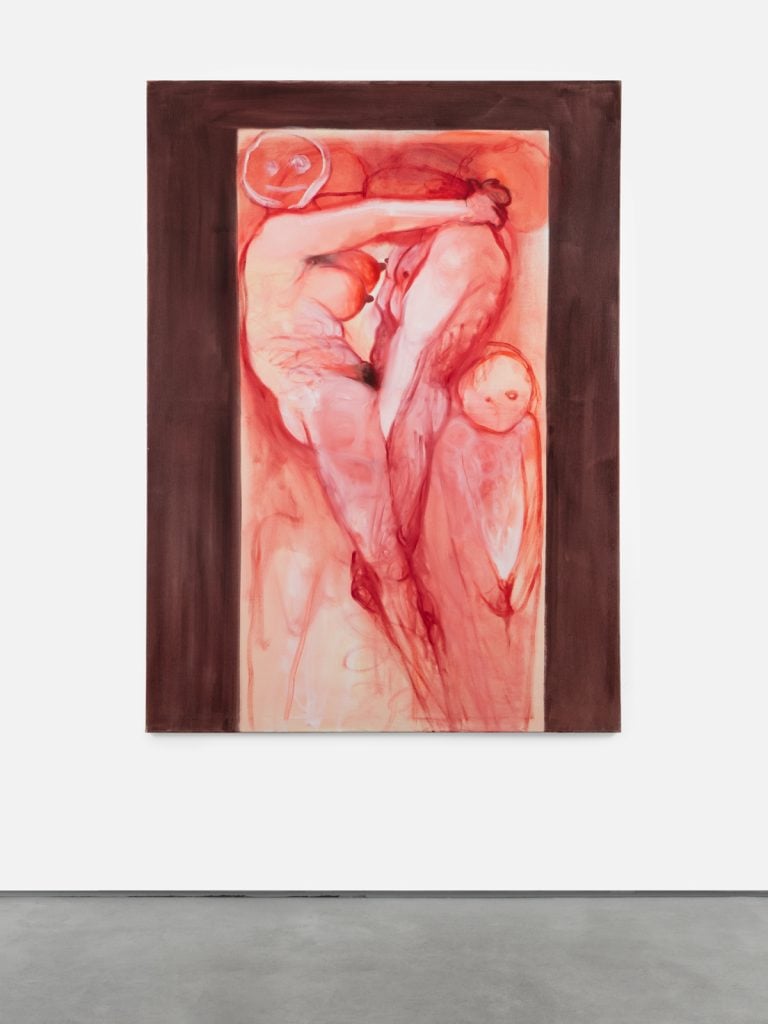

Different people moving through the show might find their challenging line at different points. For me, Monica Bonvicini’s whip of buckle-down leather belts swinging in gentle circles or Joan Semmel’s 1977 painting For Foot Fetishists felt tame, but things got closer to the bone with Darja Bajagić’s Ex Axes, reclaiming images from “women with weapons” fetish sites, and King Cobra/Doreen Lynette Garner’s butchered carcass complete with a blood-stained blonde weave. Arriving at Miriam Cahn’s 2017 fleischbild/famillienbild (Meat Portrait/ Family Portrait) would elicit a wince from even the most sexually liberated; it depicts a couple having energetic intercourse while a pint-sized, childlike figure in the foreground turns away. Cahn’s work in particular, whose recent exhibition at Palais de Tokyo ignited a firestorm of controversy in France, seems to sit right on a knife’s edge of what can be socially acceptable today.

Miriam Cahn, fleischbild/famillienbild (2017). ©Miriam Cahn. Courtesy of The Artist and Meyer Riegger, Berlin/Karlsruhe.

Photo: Katie Morrison / Sadie Coles HQ, London.

More leather is to be found in the Lisa-Marie Harris sculptures and wall-mounted reliefs at Cooke Latham Gallery, which respond to body shaming and sexually objectifying comments the artist has gotten over the years, and comment on the policing and hyper-vigilant monitoring of the female body as a response to sexual violence enacted on women. Elsewhere, at Stephen Friedman, Sasha Gordon’s surreal self-portraits—including images of herself as living topiary and as a cat—explore the alienation of unconventional human bodies and questions of her identity as a queer Asian American woman in a show titled “The Flesh Disappears, But Continues to Ache.”

The gargantuan leaps forward in the development of A.I. have pushed the tone of the art-tech conversation to a fever pitch; technologists are sounding the alarm about the threat A.I. poses to human existence itself. But even before this recent turn in the discourse, the destabilizing effects of the internet and its flood of information and distractions have been giving artists ample material to work with.

At Sadie Coles HQ’s space on Davies Street, Lawrence Lek’s ultra-prescient “Black Cloud Highway 黑云高速公路” unseats the myth of technological progress in an age of artificial intelligence. Lek’s entrancing 11-minute film Black Cloud follows a lone surveillance A.I. in an abandoned city—SimBeijing, a replica of the Chinese capital built by a tech company to road-test self driving cars. It reports accidents until all other A.I.s are banished, leaving it alone in the metropolis. It then engages a self-help therapy program to help it cope. The aura of post-humanity fills the viewer with dread that we are on the precipice of an abyss, a feeling aided by a thumping soundtrack by Lek and Kode9.

![Lawrence Lek, <i>Black Cloud 黑云</i> [film still] (2021). ©Lawrence Lek, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London.](https://news.artnet.com/app/news-upload/2023/06/08_Lawrence_Lek_Black_Cloud_%E9%BB%91%E4%BA%91__2021__film_still__11m_canonical-1024x576.jpeg)

Lawrence Lek, Black Cloud 黑云 [film still] (2021). ©Lawrence Lek, courtesy Sadie Coles HQ, London.

At Gazelli Art House, Jake Elwes’s exploration of A.I. and machine learning, “Zizi – Queering the Dataset,” disrupts standardized facial recognition technology by feeding it thousands of images of drag performers. And Machine Learning Porn (2016) exposes the warped understanding of human biology by an algorithm trained to remove explicit imagery by tasking it with creating pornographic visuals.

Maisie Cousins, Green Head (2023). Photo courtesy of T.J. Boulting.

What these standout shows have in common—the abstract paintings, the intellectual provocations, the tech experimentation—is that they are all grappling with the specific difficulties of contemporary living; the isolating and scary present, the uncertainty about the future, and the inadequacy of the systems, forms, language, rules, and social mores we have available to answer to this existential nausea.

Many of these works have found a way to express this feeling, and also to propose a way through it. They express a desire for nuance, for queering and questioning labels and boxes, and for opening up space for other ways of thinking, being, and seeing that are undefined. Something Garrels said about abstraction at his Gagosian show might be extrapolated to all of these works: “At the end of the day, it’s the individuals there on their own terms, struggling to find meaning and coherence within this vast barrage of information.”

Javier Calleja, Still on Time (2023). Courtesy the artist and Almine Rech.

The hope is that art will return to us some sense of shared understanding about the nature of existence, the perseverance of the human spirit, and how we might sit through this difficult moment in history.

And if it all feels a little overwhelming, London Gallery Weekend has you covered too. Those in need of something to take the edge off of all this heady questioning might head over to Almine Rech, where Javier Calleja’s adorable characters offer up something of a palette cleanser.