People

Los Angeles Artist Hayley Barker’s Lush, Transfixing Landscapes Are Autobiographical Tributes to Nature

The dreamy, ethereal haze of Barker's painting foregrounds the growing fragility of the natural world.

The dreamy, ethereal haze of Barker's painting foregrounds the growing fragility of the natural world.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

Looking at a painting by Hayley Barker can produce an oscillation between a faithful depiction of a landscape and that of a dreamscape. Deeply rooted in a sense of place—with equal emphasis on “sense”—these delicate works capture the emotional state of Barker’s intimate relationship with the locations she has returned to throughout her life. “I find what I need to convey it, because it becomes like a family member or deity, almost,” she told Artnet News. “It’s something that I revere and want to come back to, that I feel generated by.”

During a childhood spent roaming the countryside of her native Oregon, Barker felt a particular affinity with the vistas of Riverwood, a forest which she has since revisited repeatedly both in person and on canvas. In 2020, the area was devastated by wildfires. “I felt like I lost my grandparent or something. It felt like losing a best friend,” is how she described a subsequent visit. “It was so utterly changed.” A recent portrayal, Jennie at the River (After the Fire) (2022), featuring a childhood friend, is a record of new life. “Its definitely not the elder forest that it was, but a fresh, young forest is trying to come up.”

It is this sensitivity to change, born from a deep communion with her surroundings, that makes Barker a landscape painter for the contemporary age. “Mourning is part of my work,” she mused. “Not nostalgia per se; it’s more just knowing that the world is a very complicated place full of divergent energies, both violent and terrifying and devastatingly beautiful.”

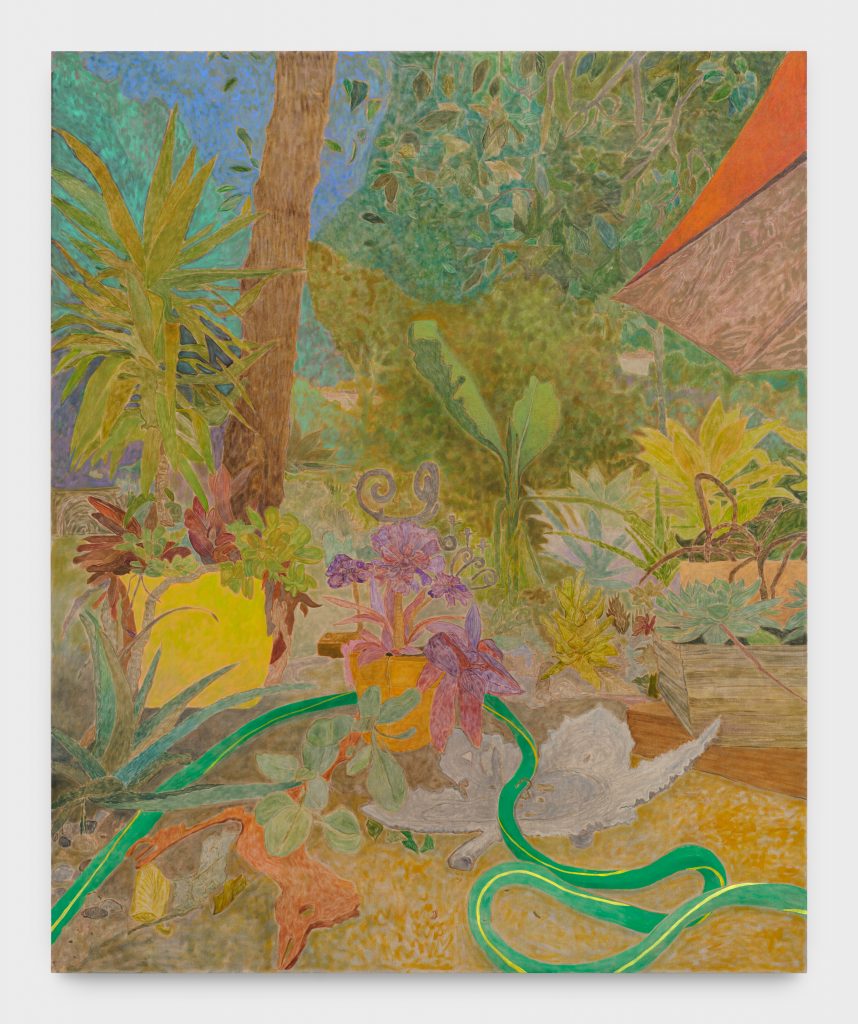

Hayley Barker, By Martin’s Porch (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Night Gallery, Los Angeles. Credit: Nik Massey.

Attuned to the specific landscapes of California and the Pacific Northwest, her work is particularly impactful for its rousing use of color to convey an underlying emotional undercurrent that realism can’t quite capture. This owes much to the early 20th-century American visionary Charles Burchfield, whose work she studied obsessively as a child. Barker also cites the Post-Impressionists, Odilon Redon, Vanessa Bell, Frank Walter, and Mamma Andersson as inspirations.

Now 49, Barker recalls an arty upbringing with parents that encouraged her to paint. “I taught myself how to use oils when I was 16 or 17, just playing in my bedroom,” she said. By the time she started her BFA at the University of Oregon in the early 1990s, however, this interest was not very in vogue. “We were just getting the memo about painting being dead,” she remembered. “It wasn’t super respected amongst my peers. I was in the punk scene and people thought painting was prosaic.”

She began making video and performance art with some drawing on the side. Her cultural references at this time were Karen Finley, Carolee Schneemann, Linda Montano, and most importantly Ana Mendieta. Barker noted, “Her work with the earth was completely formative,” eventually influencing her to attend grad school at the University of Iowa, where Mendieta had also studied. There Barker sought as a mentor the late artist’s professor, collaborator and sometime boyfriend Hans Breder. “I learned a lot about her life and experience of making work from him, which very much informed me,” she said.

Hayley Barker, Sycamore Trees (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Night Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Nik Massey.

Some years later, Barker was supporting her practice with a job taking orders at Powell’s Books in Portland, Oregon, which required spending all day in front of a computer screen. “When I got home from work, the last thing I wanted to do was edit video,” she said, recalling how she found respite by playing around with chalks and pastels instead. “It just had to happen. The world changed so quickly, video became so ubiquitous and I felt burnt out on it before it had barely started.”

Once she began painting again, the draw to landscape was immediate. These explorations were informed by the ritualistic nature of her performances and the “somatic experiences” of her video work but finally Barker was able to develop an expressive palette to complete the picture.

“I understand the landscape as having its own power and mystery and mood,” she said. “On top of that is my own personal, emotional place and how I feel in that moment. Sometimes the naturalistic color is the right fit, other times I need to pull on deeper resources to find the right colors, and that’s a more spiritual venture.”

Around 2015, Barker decamped to L.A., where she found the art scene refreshingly multifaceted. “I think that’s part of us being a bit more geographically stretched out across this broad city rather than packed together in a tight city,” she said. “Something I appreciate about the L.A. art scene is that you don’t have to have a pedigree to get going. In New York, I always felt like I had never gone to the right schools and didn’t know anybody, whereas L.A. is much more DIY.”

Hayley Barker, Terrace Path 2 (2023). Courtesy of the artist and Night Gallery, Los Angeles. Credit: Nik Massey.

She was also transfixed by the new topography, which she had first encountered during a short spell living in Long Beach as a child. “I think the landscape imprinted on me at a very young age, and I find this desertish world so compelling,” she said. “The contrasts of the colours and the fragility of life in this harsher climate.”

“The Grass is Blue,” a solo show at Shrine gallery in New York in 2020, marked a turning point for Barker with the titular work presenting a semi-fantastical, Bonnard-inspired scene with sunflowers and an archway. Using a significantly smaller brush than she had previously, Barker was able to zoom into each inch of the canvas and thinly apply small strokes that allowed, in places, the unbleached linen ground to show through.

“I finally gave up trying to paint like anybody else and brought my own quirky approach to it,” she said. “Having been more of a drawer through my schooling, I realized that I approached painting like making big drawings with paint, and that was really a breakthrough.”

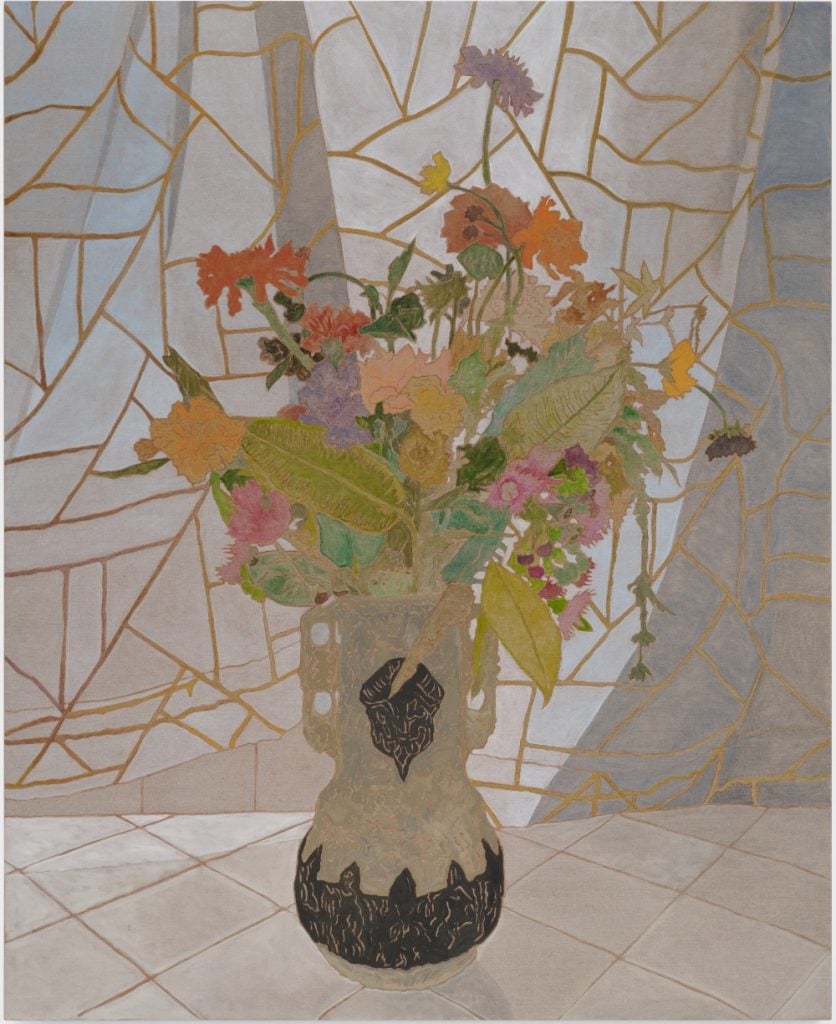

Hayley Barker, Flowers from Blair (2022). Courtesy of the artist and Night Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Nik Massey.

Barker’s discovery with the Shrine show had a clear influence on “Laguna Castle,” her solo debut at Night Gallery in L.A. in February. This new body of works was produced during a residency at Laguna Castle, a century-old hillside apartment complex in Echo Park that Barker describes as “an intentional community” originally set up by the community activist Isa-Kae Meksin. Expansive landscapes were swapped out for closely-cropped, intimate studies of the garden or a view from the window. More surprising still was how Barker’s newfound fascination with intricate detail led to a series of still lifes featuring the late Meksin’s personal effects, including necklaces and a bulletin board. More new works will be presented by both Ingleby Gallery and Night Gallery at Art Basel Miami Beach this December, and by Night Gallery at Frieze Los Angeles early next spring.

The effect of Barker’s recent development has been to heighten the scenes’ hazy ethereality and, perhaps most poignantly, their ephemerality. “Maybe that sense of mourning comes from knowing that there’s an imminent loss underway,” Barker reflected. “A loss that we can’t even comprehend. I paint because it’s something my spirit needs to survive the difficulties of the world. It’s been a saving grace to find beauty in life.”