Archaeology & History

Long-Lost Shells Collected by Captain Cook on His Final Voyage Go on View

The collection of endangered shells has survived being thrown into a trash heap.

Last December, a legendary seashell collection amassed by an 18th-century British woman miraculously reappeared. The mesmerizing specimens have now joined the new exhibition, “Shells, Shores and Beyond: A Global Collection of a Georgian Lady,” on view through November at Chesters Roman Fort and Museum in Northumberland, overseen by English Heritage. Only a fraction of the original collection of endangered shells survives today, but the 200 remaining pieces (which weathered a dump and many years in an attic) include a pristine nautilus (Nautilus pompilius) and a “Sun Shell” (Astraea heliotropum) acquired on Captain Cook’s final voyage.

Frances McIntosh holding Atkinson’s nautilus. Courtesy of English Heritage.

Bridget Atkinson built this collection. Born in 1732, Atkinson and her sister were raised at Kirkoswald by their widowed mother, who taught them how to write and sent them to study homemaking in Durham, English Heritage explained. Bridget wed a tanner named George Atkinson at 24 and had eight children. She rarely left their Cumberland county home, but solicited shells via correspondence with friends and family around the world.

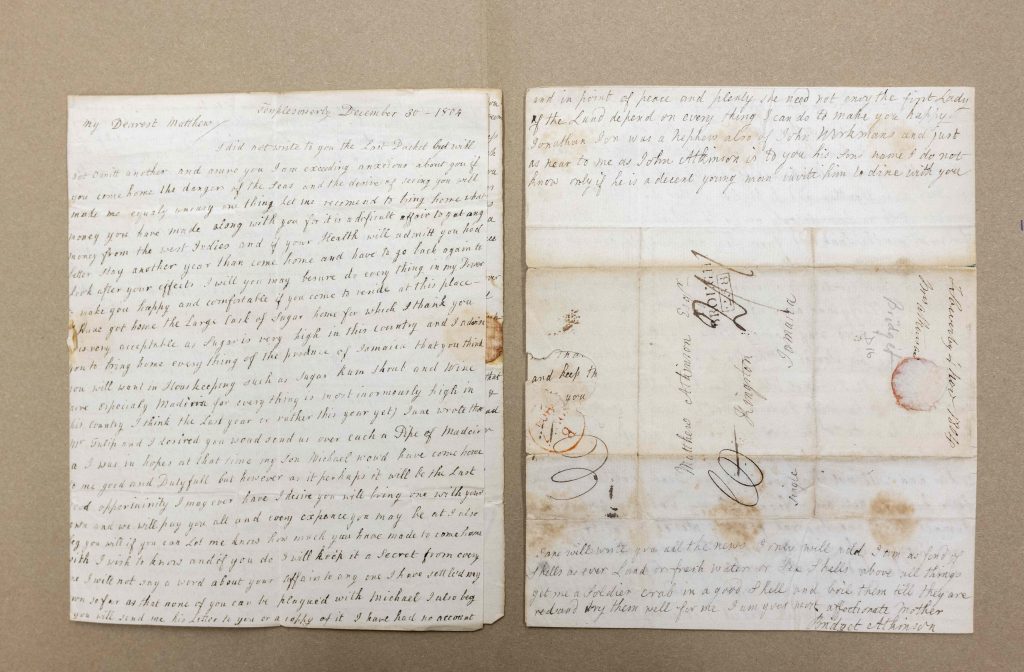

A letter from Atkinson to her son, Matthew. Photo: Phil Wilkinson, courtesy of English Heritage.

While women of this era often collected shells for aesthetics, Atkinson’s efforts were notably academic, as evidenced by her letters and library. In 1813, the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle-upon-Tyne made Atkinson its first honorary member, while still barring women from formal membership. After her death the following year, the collection fell to Atkinson’s youngest daughter, Jane, who continued collecting. When Jane died, she left the shells to her niece Sarah, the wife of antiquarian John Clayton. That’s how they ended up at Chesters Roman Fort.

“Whilst most of the shells were sold along with the Clayton estate in 1930, around 200 of Bridget’s shells remained on display,” reads the exhibition page. NPR reports that around that year, Atkinson’s then-living descendant “managed to gamble away his inheritance.” Chesters Roman Fort lent the surviving collection to the zoology department at Armstrong College, now Newcastle University, where it was dumped in the garbage during a spring cleaning in the 1980s. A young lecturer named John Buchanan spotted the specimens in the trash and saved them for himself. The shells remained in his family’s possession until they were discovered in an attic and donated back to the museum last year, reunited with the lone massive clam that managed to stay in the museum’s stores.

Frances McIntosh with Atkinson’s shells. Photo: Phil Wilkinson, courtesy of English Heritage.

“We’ve always known about Bridget Atkinson’s collection but had believed it completely lost,” English Heritage’s collections curator Frances McIntosh said in a statement. “To discover that the shells have not only survived but been kept safe and loved all this time is nothing short of a miracle.” Beyond its visual intrigue, the cache humanizes life under British imperialism, while demonstrating that era’s overarching environmental legacy. Numerous creatures in the collection, like the extinct Distorsio cancellina, are either gone or endangered today.