“My mother was a restorer, she repaired broken things,” the late artist Louise Bourgeois said in a 1992 conversation with the author Christiane Meyer-Thoss. “I don’t do that. I destroy things. I cannot go the straight line. I must destroy, rebuild, destroy again.”

That perception of herself may come as a surprise to anyone who has seen Bourgeois’s prolific body of work. To those of us on the outside, her contribution—so far ahead of its time—is anything but destructive, though it can certainly speak of torment and violence.

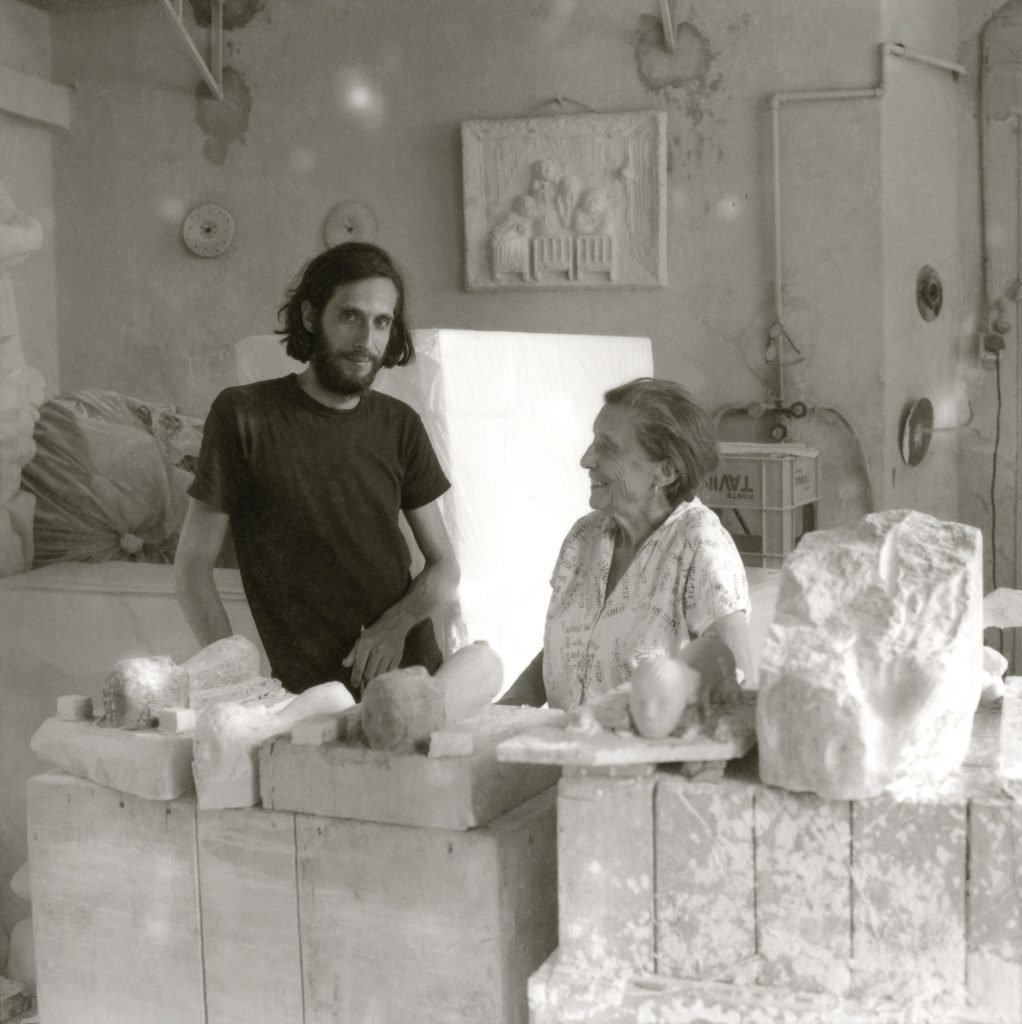

Bourgeois’s propensity to destroy her own work is nevertheless well-known. And perhaps by no one better than her assistant during the last 30 years of her life, Jerry Gorovoy. As the long-time manager of her work, Gorovoy also serves as president of Louise Bourgeois’s Easton Foundation. He is also a curator, and has organized a forthcoming exhibition that looks at Roni Horn’s work through the prism of Ingmar Bergman’s films, opening at Hauser & Wirth Monaco on September 22.

The first survey of Bourgeois’s late fabric creations, “The Woven Child”, is now on view at the Gropius Bau in Berlin, through October 23, following its debut at the Hayward Gallery, London. The show examines the “rebuilding” or repairing gesture within Bourgeois’s process, through weaving and sewing, and in response to destruction.

Gorovoy wrote to Artnet News about the show, grappling with Bourgeois’s inner demons, her belief that artists are like scratched records endlessly returning to old traumas, and what mattered to her most.

Louise Bourgeois descending the stairs in her home on West 20th Street in NYC, 1992 © The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Photo: Claire Bourgeois

Can you discuss the title of the exhibition, “The Woven Child”?

“The Woven Child” is the title of a fabric book that Louise made in 2003. It consists of six pages made from strips of Louise’s clothing that are woven together to form a series of images. It tells the story of a child’s development and independence as he moves away from the mother. The process of weaving directly connects to the Bourgeois family business of restoring tapestries. As a young girl, Louise helped out by drawing in missing parts that were worn away and needed to be rewoven.

As a metaphor, our identity is formed from a multitude of experiences that are threaded together. Our sense of self is something that must be constructed. Symbolically, the over and under, warp and weft of the woven page represents the dualities of conscious and unconscious, male and female, past and present, etc., that run through Louise’s work as a whole.

The weaving also signifies how relationships are held together, how we are linked to other people. The fabric works speak to her powerful and lifelong fear of separation and abandonment.

Am I right in thinking that fear of abandonment was largely due to her father’s affairs and frequent absences, as well as the early death of her mother?

Louise spoke about her father enlisting to fight in World War I, and how her mother followed him to the various camps, bringing her along. She even visited her wounded father in the hospital when she was just four years old. Certainly, her father’s dalliances and her mother’s illness (and subsequent death) contributed to her fear of abandonment, but I think the origins of this fear lie much earlier.

“Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child,” Installation view, Gropius Bau (2022). © The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Photo: Luca Girardini.

Bourgeois has described her work as “truth-seeking.” Could you share any stories about any works which were particularly important in her quest for truth? Did she reveal more about what each garment and sculpture symbolized in those works?

Cell XXV (The View of the World of the Jealous Wife) is one of many self-portraits in the show. Three garments from different moments in Louise’s life hang within a wire mesh enclosure. The central garment has two large white marble spheres placed underneath it, which can be read as breasts, though they also form a phallic figure. A fancy blue cocktail dress hangs on a black form on the other side of the cell.

Louise saw the garments as defining not only distinct moments in time but different aspects of herself. For example, you have the wife, the mother, and the artist.

Louise’s fear of abandonment led to ferocious jealousy. She herself traced these feelings back to her childhood, which was marked by her father’s frequent absences and philandering and by sibling rivalry, which included a competition to care for her chronically ill mother, whom she wanted to watch over on her own. Much later, Louise felt jealous of the female students who studied under her husband, Robert Goldwater, a famous professor and art historian.

Her writings bear ample witness to the murderous and suicidal impulses that her jealousy generated. It was one of her many destructive impulses, causing her at times to sever relationships entirely. The pattern was consistent: jealousy, whether real or imagined, led to paranoia and aggression, which was then followed by guilt. This continued to be operative throughout her life, and it even colored our relationship.

Ultimately, I felt that Louise had come to understand the mechanisms of her insecurities but was unable to overcome them. It was something in herself that she accepted, and anyone close to her had to accept it as well.

Louise Bourgeois, The Good Mother (detail), 2003. © The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Photo: Christopher Burke.

You have mentioned you tried to discover the origin of her anxieties, and also found that ensuring Louise was able to work was the best way to help keep her demons at bay. Why do you think that was the case?

Louise was certainly calmer and easier to be around when she was working. Her anxiety was channeled into the energy needed to realize a work. The discovery of her psychoanalytic writings helped me to understand the origins of certain anxieties that would suddenly and unpredictably erupt. [I discovered the psychoanalytic writings while she was alive, and she knew and approved of the fact that they would be published eventually.]

I understood these as moments in which she was in pain, despite the fact that she could be so destructive. I would try to connect the present moment of chaos with whatever it was from her past that had triggered it. Her fears and rages were certainly linked to infantile compulsions. This again relates to “The Woven Child,” the child that has to grow up.

What do you mean by “infantile compulsions”?

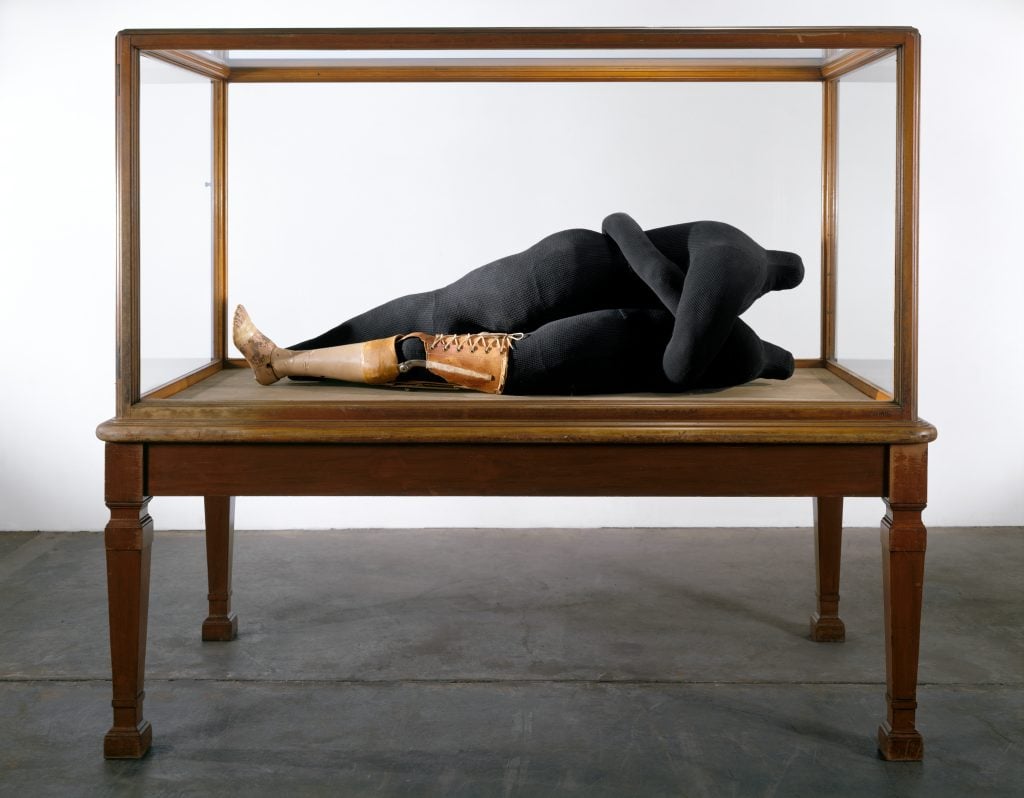

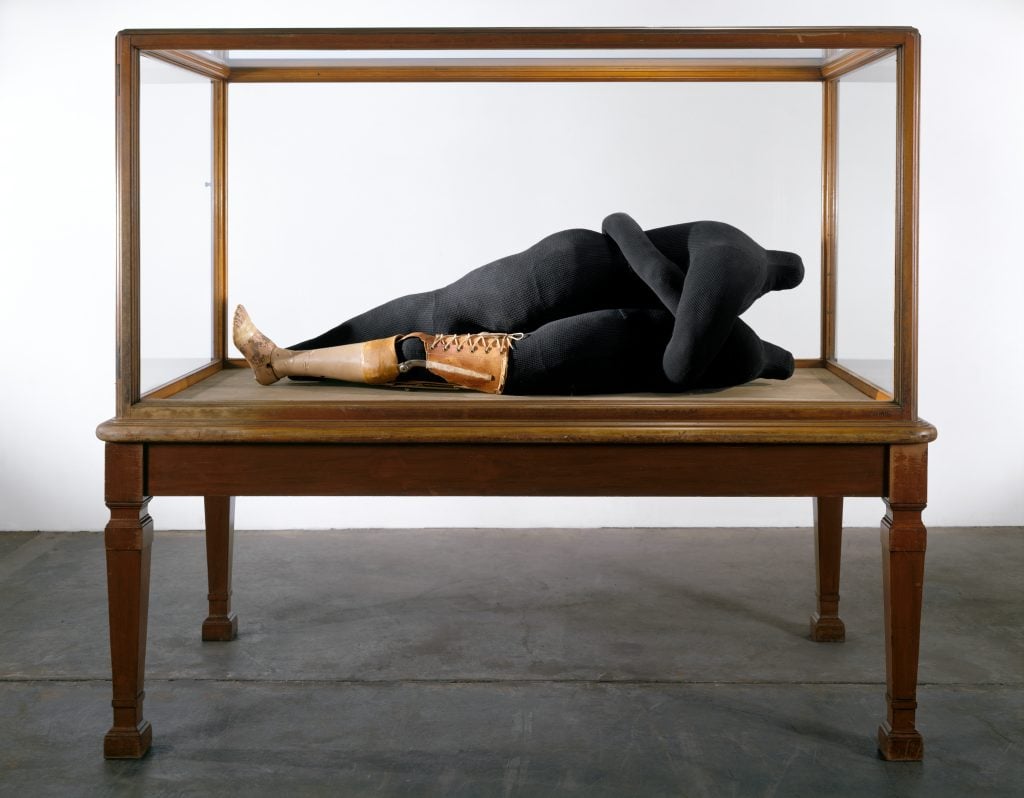

Compulsions are an acting out of certain feelings that arise early in the development of a child. Louise repeated these sorts of traumas unconsciously, through particular thoughts and actions, as well as through making art. One of her important Cell sculptures, CELL (YOU BETTER GROW UP) (1993), deals directly with the inability to shake these compulsions, to escape one’s dependency on others, and to not be afraid. Louise felt the artist was someone who never succeeded in going through the rites of passage.

Louise Bourgeois, Couple IV, 1997. © The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Photo: Christopher Burke

What did she feel held artists back from shaking their childhood compulsions?

Louise never had an exalted view of the artist. She believed that one becomes an artist because they’re unable to do anything else. Something had to occur on a psychological or emotional level to keep them from going through the rites of passage. The artist is condemned to a life of repetition, a recurrence of some sort of trauma that’s like a scratch in a record. She had higher regard for writers, since they can convince someone of something, whereas art is just a means of self-expression.

With this late body of “woven” works—including some of her last creations—did she finally succeed at finding that truth she sought?

I wouldn’t say so. The late fabric works are just another chapter in Louise’s life. They answer another set of problems that she was grappling with at the time. All of Louise’s art was an attempt at understanding and overcoming her complex feelings, so in that sense she was always searching for truth and self-acceptance.

I don’t think the late work represents a summation. Certainly, it represents a concern for what would happen to her belongings when she was gone. Specific objects and clothes were symbolic of memories and past moments. By incorporating these elements in her art, she was giving them a value and a life beyond her own.

In addition to the dualities symbolized by the weaving process—the warp and weft—plus the importance of tapestry restoration in her youth, were there other psychological puzzles she was sorting out here?

Weaving was only one of the many techniques Louise employed in making the fabric works. I don’t see a difference between the flat woven pieces and the more realistic fabric couples that cling to each other and hang from a single point. At this time, she was unconsciously moving towards an identification with her mother. In all of her depictions of the mother and child, it is important to realize that Louise saw herself as the child. She felt she was looking for a mother.

“Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child,” Installation view, Gropius Bau (2022) © The Easton Foundation/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2022, Photo: Luca Girardini

Did you visit many art exhibits with her, before she was more homebound? Could you discuss how she responded to viewing other artwork, or spending time around other artists?

Louise felt a camaraderie with other artists, particularly with younger artists. Though she was highly critical, she enjoyed looking at their work and hearing about their struggles. I think looking at the art of others gave her a chance to get outside of herself.

Louise’s Sunday salons with other artists were a way of staying in touch. She enjoyed seeing an artwork together with its maker, which is something you don’t have going around to galleries, though we often did that too before she stopped going out. The more famous Louise became, and the more public recognition she received, the less she wanted to go out into the world.

I understand Louise Bourgeois wrote down what many of her works symbolized, because she was fed up with misinterpretations of them.

Louise was a natural writer and talker. It was important for her to write down her memories or ideas. What Louise recorded were the essential motivations behind what she made, or the ideas that the form or image suddenly generated in her. Her statements were not meant to act as a closure to the actual meaning of the work itself. Louise always said that there was magic in the making of a work of art, that there was something in the process that cannot be captured or explained. Hopefully, this magic would transfer to the viewer.