Artists

‘Everything I Feared Has Come True’: Luc Tuymans Speaks with Philip Tinari at His New Beijing Exhibition

The artist's major new retrospective at UCCA Beijing reveals a profound connection to China's art scene.

The artist's major new retrospective at UCCA Beijing reveals a profound connection to China's art scene.

Artnet News

Luc Tuymans has returned to China, where he shares a deep connection with the art scene. His influence began in the early 2000s, as his work became visible through China’s art academies and he engaged in curatorial projects that promote Sino-European exchange. Tuymans has become a pivotal figure in the dialogue between the Chinese and global art worlds.

“Luc Tuymans: The Past” opened last week at the UCCA Center for Contemporary Art in Beijing, where it will remain on view through February 16, 2025. Curated by Peter Eleey in close collaboration with the artist, the exhibition unites 87 works, and more than 100 canvases, which trace the arc of Tuymans’s career from the late 1970s through last year. Drawn from some 56 private and institutional collections, the exhibition is among the artist’s most significant retrospectives to date, and arrives in a context where he has a long history of collaboration and inspiration.

Shortly before the opening, Tuymans and UCCA director Philip Tinari discussed the ideas behind, and hopes for, this ambitious exhibition.

Peter Eleey, Luc Tuymans and Philip Tinari at the press conference. Courtesy UCCA Center for Contemporary Art, 2024

Philip Tinari: I wanted to start by asking a little bit about your involvement with China over these many years. I was just looking at photos from UCCA’s grand opening in November 2007. There’s an image of you present at the dinner, just a few weeks after the end of “The Forbidden Empire,” an exhibition of Chinese and Belgian paintings from the 15th through 20th centuries that you’d curated at the Palace Museum here, in collaboration with Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels.

Luc Tuymans: I’ve always been fascinated by China. My earliest encounter was due to one of my favorite early 20th-century Dutch writers, Jan Jacob Slauerhoff, and the title of that exhibition comes from one of his books. He was a world traveler and even translated some classical Chinese poetry into Dutch. The chance to work in the Forbidden City was incredible, to combine work from the 15th century in the lowlands with the Chinese masters of the Ming and Qing, and right up through the early 20th century. And after that project, I worked on another exhibition, “The State of Things,” which brought together Chinese and Belgian contemporary artists.

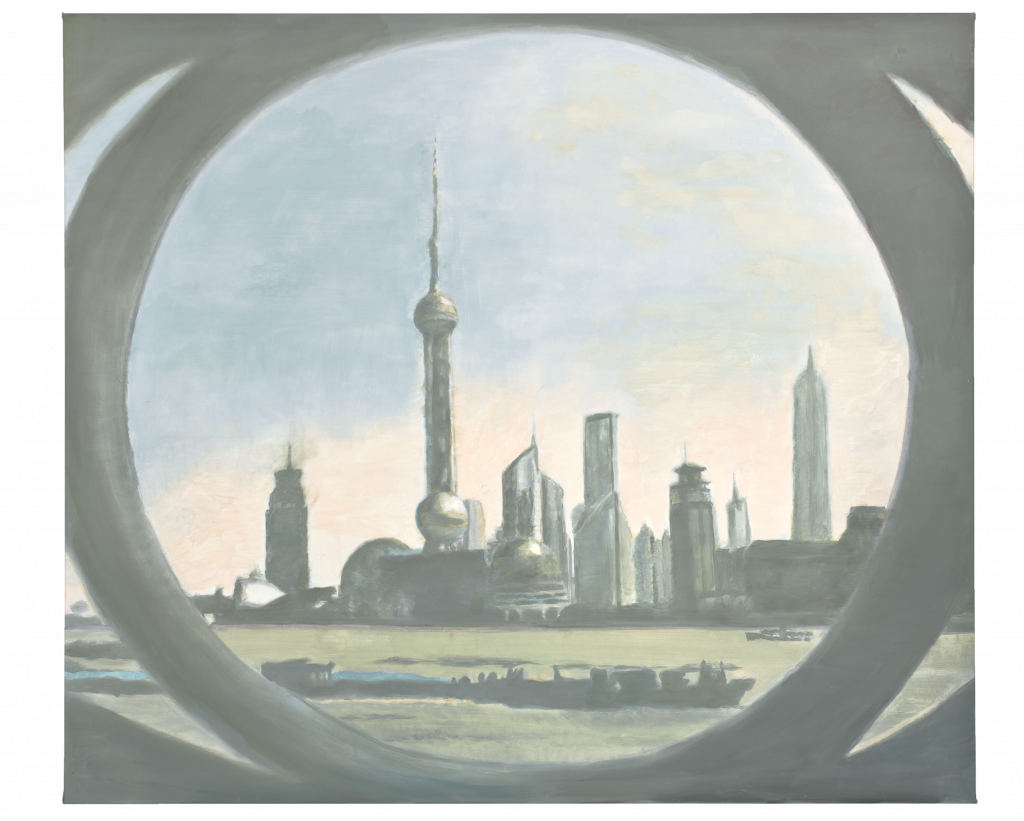

Luc Tuymans, Shenzhen (2019). Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner.

But in a way my real encounter with China is because of one publication, my Phaidon Press monograph, which was distributed in 60,000 copies all over the world, including here, where it was actually counterfeited. So when I first visited China in the early 2000s, some artists came to visit me, people like Wang Xingwei and Zhang Enli, and we became good friends.

These longstanding friendships actually grew over the years, so to speak. And after those two curatorial projects, there was an idea of me doing a show in China, which got postponed many times for many different different reasons. And now finally we can do the show. It’s an emotional thing, because of the idea of patience. And I feel it is a huge responsibility to finally show my work to people who might have seen it in reproduction and not for real.

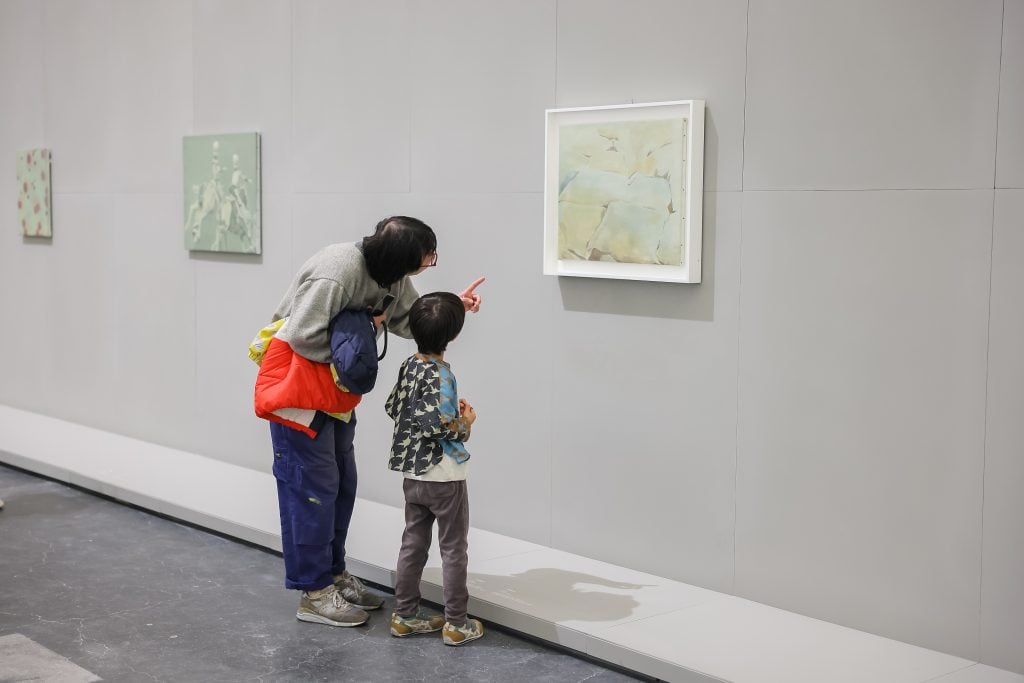

Installation view of “Luc Tuymans: The Past,” UCCA Center for Contemporary Art2024. Photo: Sun Shi, courtesy UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Tinari: I want to ask about your work as a curator. We know the story of your first exhibition in that hotel swimming pool in Oostend, where you acted as your own curator. In 2007 there was “The Forbidden Empire,” and then in 2009, you co-curated “The State of Things” with [then National Art Museum of China director] Fan Di’an and Ai Weiwei—something that could never happen today. Was this kind of curatorial work something that began for you in China?

Tuymans: No, the very first show that I curated, long before that, was called “Troublespot Painting,” in 1999, which I organized with another painter, about the problematization of painting, which meant you have painting on a two-dimensional level, but also when it becomes an installation. That was my first real curatorial project.

Tinari: It’s interesting because both “The Forbidden Empire” and “The State of Things” were structured on this idea of a cultural binary between China and Europe, ancient and modern.

Tuymans: Absolutely. But it was also, for me, important to use this moment of international exchange to open new possibilities in China. Many of the Chinese artists we chose for “The State of Things” had never before shown in the National Art Museum of China. There were places like UCCA, but the official institutions were not open to contemporary art, these artists were not shown there. And we were able to use this occasion to accomplish something that had never been done before. That for me was a very important thing to do.

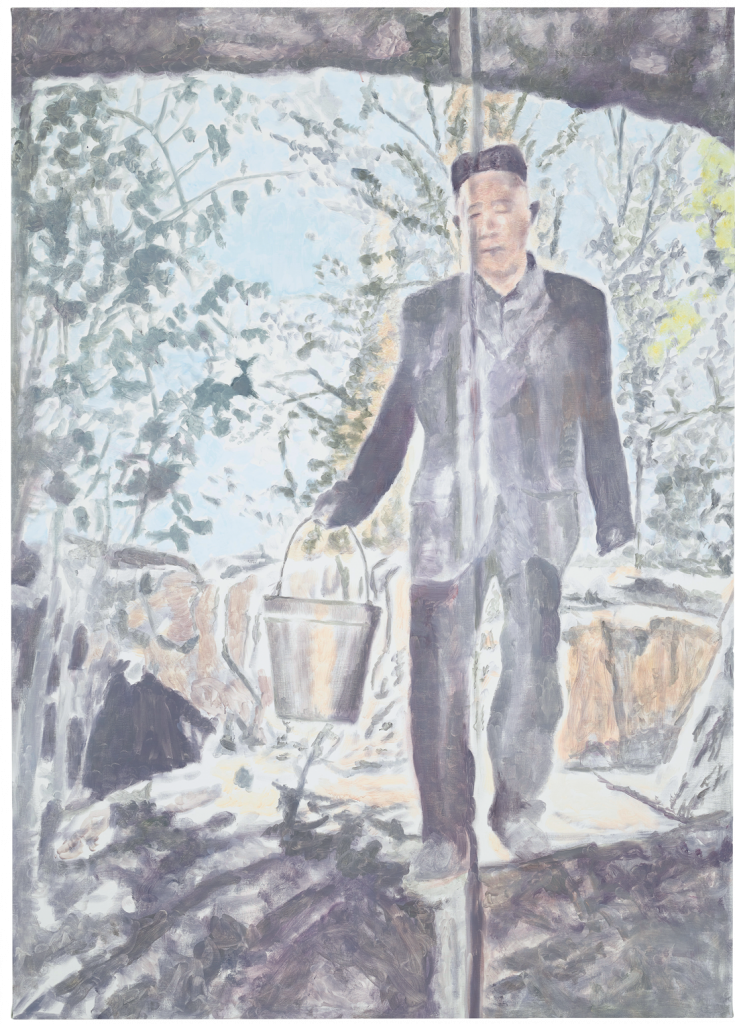

Luc Tuymans, Inland (2018). Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner

Tinari: I remember that moment, before Instagram, at the heyday of Ai Weiwei’s blog. One time you had a meeting about the show at his studio, and he posted all these photos of you and Fan Di’an visiting his studio, which was at that time quite a statement. It was this moment of openness in the Chinese system, actually. The individuals aside, you would never see this kind of experimental, contemporary project in a national museum today.

Tuymans: No. We’re living in different times. Times change.

Tinari: That’s a good segue to our exhibition here, “The Past,” where we have a huge selection of your works, going all the way back to 1976, and covering all of your major periods. The show was curated by Peter Eleey, working very closely with you. You came up with the title, and the initial concept for the space. How has your thinking on this exhibition evolved?

Tuymans: I think, first of all, I wanted to make clear that since it’s been such a long journey, that it should be, first of all, a very comprehensive show. It’s chronological—not totally chronological, but mainly so. I think we agreed upon that very early on. We also decided to show the diversity in the work, but also to focus on what would be beautiful on the space. We built a kind of space within the space, though it still remains a single space. And that, the architecture, was the particular challenge of this show—that you have everything in one place, so to speak. This gives you the possibility to look at how the painting changes.

Tinari: Your exhibition titles are always so clear, and they’re generally quite simple. And this time we just decided to call it “The Past.”

Tuymans: Yeah, I think it’s an interesting thing because the past, of course, implies the idea of a future in a sense, or in a more dystopian sense, maybe not. But, it’s interesting because, In a certain sense, what we are going through on a global level has to do much more with the past than it has with the future. Actually, although there is a technological, enhanced evolution going as we speak, the other side is the content and what people and humanity as a whole wants to propel forward is something completely different. So that’s the discrepancy, which is interesting. For me it’s important to do this show at this particular moment, because everything I feared has come true. And so in that sense you’re recuperated by reality. The new reality is actually part of the past.

Installation view of “Luc Tuymans: The Past,” UCCA Center for Contemporary Art2024. Photo: Sun Shi, courtesy UCCA Center for Contemporary Art.

Tinari: It’s always interesting to think about the particular context and urgency of any exhibition. And in addition to this temporal element, here we are, in an institution that was actually founded by Belgian collectors [Guy and Miriam Ullens], and that has been committed to the same kind of cross-cultural communication we were just talking about. You have been called a cultural emissary. How do you see your own role in this ongoing conversation between China and Europe, between East and West?

Tuymans: Belgium is a very particular country because Belgium is a young country. It was only founded in 1830. After the Napoleonic Wars, it was given back because the Dutch king didn’t know what to do with it. And the Rothschilds bought it. It was the first, smallest tax paradise on the globe. And they had to find a king for it. But the region always has been very powerful and very wealthy in a certain sense, especially culturally. But we have been overrun by numerous foreign nationalities and all that. So in that sense, there is an element of realism in the whole understanding of what is happening.

Luc Tuymans, Instant (2009). Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner.

And then there’s the region I come from. There’s an element of pragmatism in it too, in a sense. And I think that is the sort of binding element that makes it possible to project something outwards. The Belgians were always very good to project themselves outwards, perhaps because looking inwards is a disaster. It’s a country of individuals in a sense, it was never a country of groups. It was never very organized. And so it’s very good in terms of being creative. I think this sort of curiosity that is part of its DNA.

Tinari: You are a child of the 1950s, you very much belong to the postwar moment. The whole discourse in which you grew up, began your career, and even existed perhaps until very recently was in the shadow of the Second World War. Today that order is facing challenges and showing fissures, whether in terms of the security architecture, or the moral lessons learned. Do these kinds of questions about the world system come to you in the studio?

Tuymans: Not necessarily in the studio. At a certain stage, it just felt more like an intuition in a sense, because it started like that, so the whole phobia with, let’s say, the Second World War was based on two elements, one autobiographical and one larger. My family has two histories, two sides—a Flemish father and a Dutch mother, collaboration and resistance. Out of that, the marriage grew, that was unhappy. And mostly during dinner, when this history came up, it was immediately drawn back to these specific positions.

Luc Tuymans, Der diagnostische Blick V (The Diagnostic View V) (1992). Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner.

Tinari: So the political was deeply personal.

Tuymans: Exactly—geopolitics, European history, all of that. But it was also a blame game. On a larger level, it was also interesting because this was the moment that empires disappeared, and the idea of the European community emerged as the only way out. And the second element was the Holocaust, which was a sort of psychological breakdown. All of this was a foreboding of what we are actually living now, and therefore I thought it was a very interesting building block to start from: Instead of making art from art, I would start to make art from a specific, from an element of history which is near, which is close to my understanding.

Tinari: There are works in the show on so many of these themes—on your childhood and personal history, on elements of recent European history. But there are also moments where the distant enters the frame. I’m thinking of a painting like Morning Sun (2003), of the Pudong skyline in Shanghai. Or there is the painting of Shenzhen as seen in a YouTube video, first shown in 2020, when China was cut off from the world.

Tuymans: I made the painting of Shanghai after my first visit. There was this feeling then, this vision of the future when you were at the Bund and you look at the new development. By now that vision of the future is already in the past. And yet one has to admit that the way China changed and the way the development went at such a specific speed is extraordinary, and fascinating as we’re dealing with a very old civilization. That picture in a way is about this element of resilience.

Luc Tuymans and Philip Tinari. Courtesy UCCA Center for Contemporary Art, 2024.

Tinari: And that is what makes this show interesting at this moment—after this 40-year stretch where China stood for some kind of exceptional, hypercapitalist speed, it is now questioning its own future like everywhere else.

Tuymans: That makes it even more interesting. Absolutely.

Tinari: It’s also worth mentioning that this is not exactly the most obvious time to be making a show like this in Beijing—it’s not that frothy environment of a decade ago, and this is such a rarity. The last thing I wanted to ask you about is reception, because while your approach has been endlessly discussed and analyzed, one thing that comes back a lot is the space that you leave for imagination, a certain ambiguity, not always saying what the thing is or why you decided to do it in a certain way. How do you think about the audience for this exhibition and how they may approach it and what they may take from it?

Tuymans: First of all, I also do think that the fascination that some of this part of the world might have with my work is due to the sense that they also have a clear understanding of understatement. Because it’s also a little bit in the culture in a sense. And I think that makes it intriguing for them and makes it intriguing for me. So that’s a link, that there is the ambiguous situation to not always directly approach the target, but to approach it from a more careful way and to approach it gradually.

If you look at Chinese culture, you could also say that sometimes things are going to be very big. But things can also be very small and intricate, so these are two extremes that live in this culture. And then in between there is a big zone, so to speak. And I think that element of understatement is probably where these places could meet. Where you could make this sort of thing happening. I think that might be some kind of idea of how the reception would be. Apart from all the other things.