Photo: courtesy Cardi

Amah-Rose Abrams

The work of Lucio Fontana has been the subject of a kind of renaissance over the last few years, both at auction and on the receiving end of the critics’ pen.

Arte Povera and other turn-of-the-century movements in Italian art have always been considered important in the history of art, but in recent years, its artists—along with Fontana—have seen a remarkable market surge. It is widely accepted that Fontana’s most important work came later in his life, once he had honed his Spatialist concept and began producing his iconic slashed canvases, but his career was more than just one body of work.

Born in 1889 to Italian immigrant parents in Rosario, Argentina, the artist’s early years were divided between Argentina and his parents’ native Italy. His first exhibition, “Nexus,” was held in 1962 in Rosario alongside a group of young Argentine artists, and after returning to Italy in 1927, Fontana, who had previously worked with his sculptor father Luigi Fontana, studied under the classical sculptor Adolfo Wildt at the Accademia di Brera from 1928 to 1930.

Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale (1957). Courtesy of Robilant & Voena.

After graduating in 1930, Fontana held his first solo exhibition at the Milan gallery Il Milione and spent the following decade working in Italy and France, both on his own work and in collaboration with other artists. Though he was already at the forefront of the European art scene, his early sculptures and experiments in ceramics were not yet in the unique artistic language that he is so famous for today.

Lucio Fontana, Crocifisso (1950). Courtesy of Studio La Città.

In 1940, shortly after the beginning of the Second World War, Fontana returned to Buenos Aires where he and some of his students published the Manifesto Bianco (1946), which read: “Matter, color, and sound in motion are the phenomena whose simultaneous development makes up the new art.”

The text also stated that they were “abandoning the use of known forms of art and we are initiating the development of an art based on the unity of space and time.”

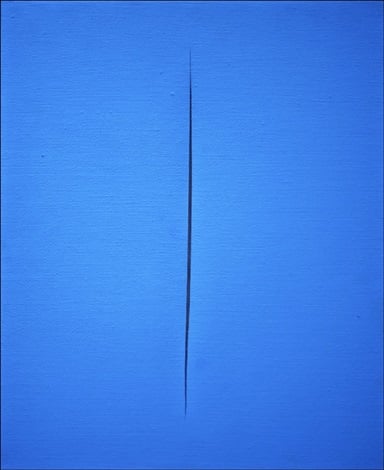

Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale. Attesa (1960). Courtesy of Robilant & Voena.

It was in this text that Fontana began to formulate what later became known as Spatialism, a theory which he went on to refine in a series of manifestos spanning from the 1940s to the 1960s. The ideas he explored were often concerned with tapping into the subconscious to create art, and inventing new forms through which to express them.

On returning to a post-war Italy in 1948, Fontana was confronted by a Milan that bore the scars of the allied bombings, in which many buildings and monuments were destroyed. It was the following year that he exhibited for the first time his Ambiente spaziale a luce nera (Spatial Environment) (1949) at the Galleria del Naviglio in Milan, filling the space with a remarkable amoeba-shaped structure, which hung in the dark, lit only by neon light.

Lucio Fontan,a Concetta Spaziale Attesa, (1964–1965). Courtesy of Mazzoleni.

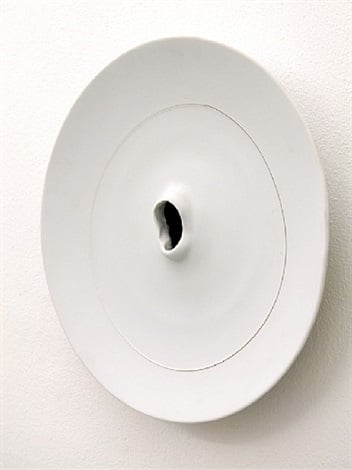

It was also at this time that Fontana began to make the works for which he is best known: his revolutionary slashed and pierced paintings. Based on the concepts he formulated in his Spatialism manifestos, he began cutting through the surface of monochrome canvases in a seemingly violent act that was entirely new to the tradition of painting. He would go on to explore this conceit over the course of his life, with his subsequent work divided loosely into two series: Buchi (‘holes’), beginning in 1949, and the Tagli (‘slashes’) that came later in the mid-1950s.

“With all due respect to the genius Picasso and to Boccioni, this infamous ‘hole’ is not a hole in the canvas but in the first dimension in the void—the freedom of artists and people, to create art by any means,” explained Fontana, speaking at the Venice Biennale in 1966. “Indeed, I’d say that art is pure philosophy.”

Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale (1968). Courtesy of Studio La Città.

Fontana was exploring a third dimension with his painting. The artist would sometimes back his works with a shiny gauze fabric, which would reflect light and give the illusion of infinite depth behind the holes and slashes. He also experimented with color and finish, ranging from matte to reflective, and added fragments of glass and attached to the surface of the painting. Throughout all this work on canvas, he also continued to make sculpture that incorporated the void.

As a trailblazer, he was also lucky enough to find early critical and commercial acclaim. Fontana’s first solo exhibition in the United States was held at the Walker Art Center in 1966 and, since his death in 1968, his work has been shown at the Peggy Guggenheim collection in Venice in 2006, The Hayward Gallery in London in 1999, and the Pompidou Centre in 1987. He was notably awarded the Grand Prize for Painting at the Venice Biennale in 1966.

In tandem with growing museum representation, Fontana’s work has soared in value in recent years, with La fine di Dio (1964) fetching an astonishing $29,173,000 at auction at Christie’s London in November 2015, setting a new record for the artist. With this resurgence in value in the work of Fontana and his peers Alberto Burri and Alighiero Boetti showing no signs of a slowdown, we can expect to see more large-scale exhibitions of Italian art in the coming future.