“My work attempts to regain the things that were taken away from my people,” says the Cameroonian-born artist Ludovic Nkoth, who moved to the South Carolina in the U.S. with his family at the age of 13. “Things such as power, culture, the idea of self, and the idea of being black and proud.”

After finishing his BFA near his new home, at the University of South Carolina in Spartanburg, Nkoth moved to New York for his MFA from Hunter College, graduating in 2021. He is now based in Paris, where he will be living through next summer, as one of the four inaugural residents of l’Académie des beaux-arts.

Nkoth’s work quickly has been gaining critical and curatorial attention in recent years, with comparisons made to Kerry James Marshall, who similarly taps into art history to enliven present-day subjects; Noah Davis, whose work is also sophisticated and subtle; and Alex Katz, who maintained a long career and a unique sense of artistic vision amid rapidly changing fashions.

Nkoth is represented by Massimo de Carlo and François Ghebaly, who have shown his work at several international art fairs, including Frieze in London and Art Basel in Miami Beach. His first-ever institutional solo show in China, “Stopover,” is now on view at Pond Society in Shanghai (through December 10).

A work in progress in Ludovic Nkoth’s New York Studio. Photo: courtesy Ludovic Nkoth Studio.

Tell us about your studio. Where is it, how did you find it, what kind of space is it?

My full-time studio is in Manhattan, on 29th street. It’s very relaxed, quiet and warm, and it’s in an office building. I found it during the pandemic and was able to get a good lease. The floors are covered with small black-and-white checkers that remind me of the floors of barbershops in the South, and specifically South Carolina, where I moved to from Cameroon when I was 13. I always liked those barbershops. No matter who you are—a janitor, a doctor—you’re on the same level. There is no hierarchy. I like having that warm, playful feeling in the studio, partly because I love to host people.

I’m in Paris these days as an inaugural resident of l’Académie des beaux-arts, but before I left New York, I would invite people over regularly—artists, thinkers, musicians—to talk over drinks. So in a way, the studio is also a space to nurture community and creative thinking.

What is the first thing you do when you walk into your studio?

I start with a nice cup of black tea. That always gets the body going. I need about an hour to sit and consider what I need to do, to get my head in the game. I also have a turntable, and I spend a lot of time with it, figuring out how to release and set energy. My studio has a lot of instruments, actually.

We were going to ask if there’s anything in your studio that a visitor might find surprising.

Yeah, I used to host Music Mondays at the studio with friends. It was a way to start the week off nicely. We would get together and make some recordings, nothing that ever got shared, but I have few things we would use, like a violin and a djembe, which is a traditional West African drum that’s covered in animal skin. I have a professional-grade microphone, too, and a piano at home that I’d like to learn to play. I think a lot of it comes from growing up in the South, and the musical culture I was surrounded by. I also took a few sound-art courses for my MFA at Hunter College, where I got to experiment. That’s had its influence too.

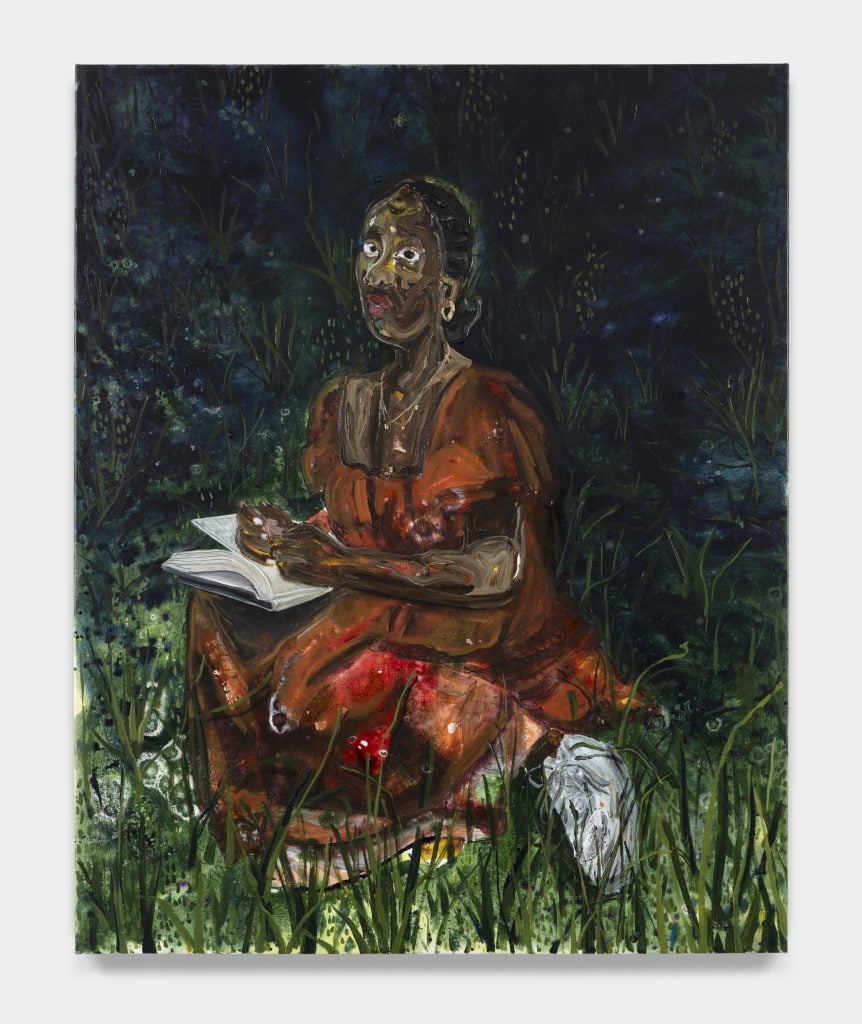

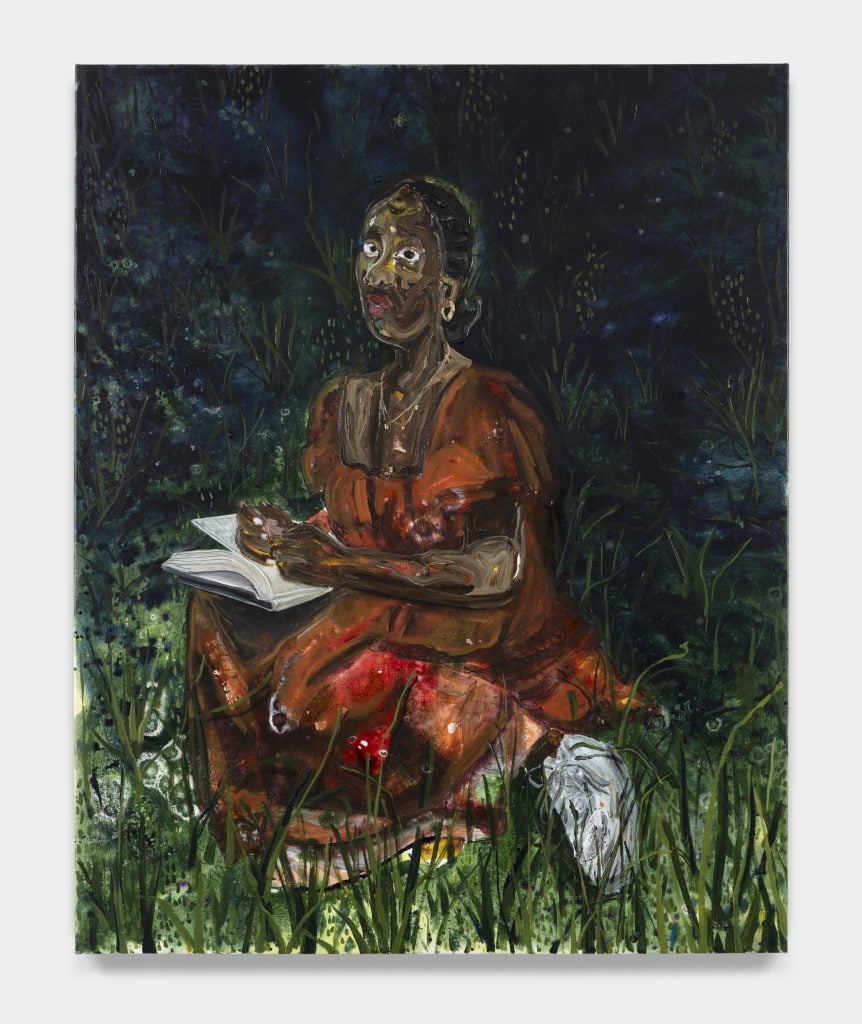

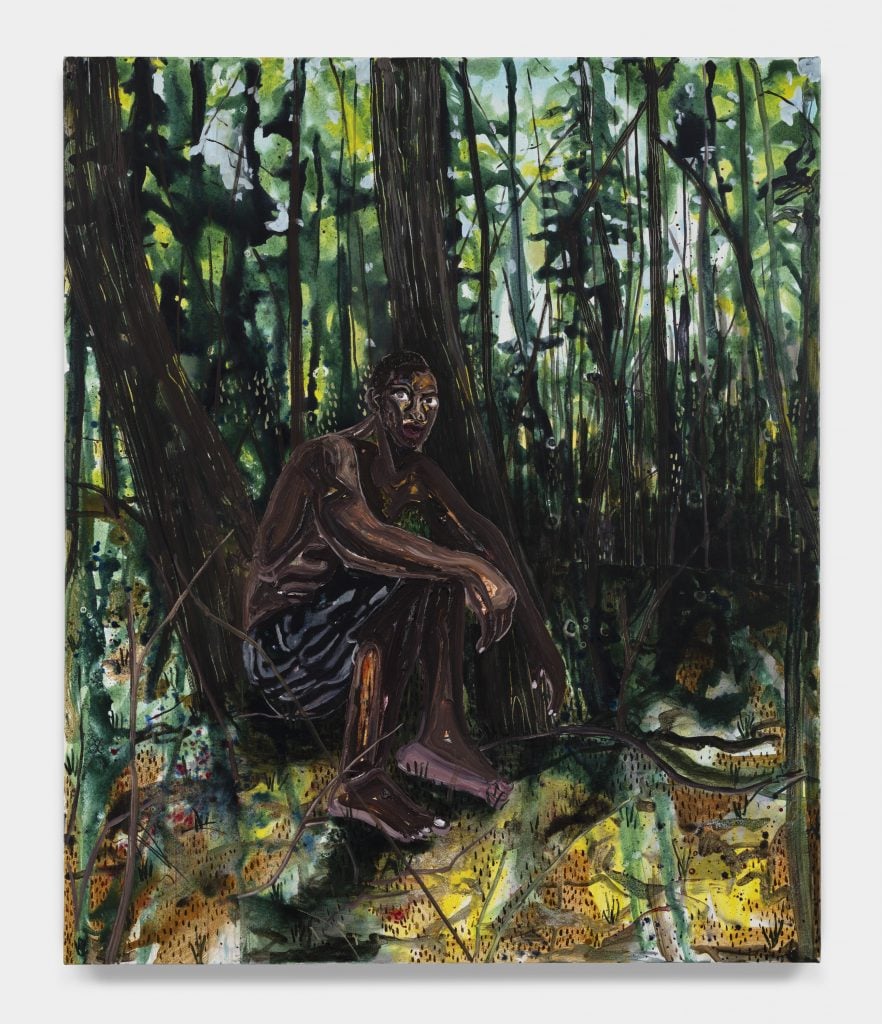

Ludovic Nkoth, Jane (2022). Photo: © Ludovic Nkoth.

Have you seen any exhibitions lately that have affected you particularly?

Yes, “Monet Mitchell” at the Fondation Louis Vuitton. It was life-changing. It’s so fascinating to see the overlaps between these two legends from different times, and how they saw the same things. I’ve seen Monet’s paintings before, but I didn’t pay much attention to them at first. Walking around, I realized how much harmony he was able to produce out of wildly different colors, whether the brightest pink or orange. Nothing fights for attention. It just flows. With Joan, she was doing the same thing, but with movement and not just color. Monet took his time and was patient, and Joan was working fast, just trying to get ideas out there. It’s the difference between care of touch and rushing—for lack of a better term—to get things out there. And still, there’s so much that’s the same. I’m on a new path to understanding color harmony now.

Is that what you’re working on now?

Yes. I have a show now at the Pond Society in Shanghai, “Stopover,” and since then, I’ve been working on developing new ways to mix and understand color. I want to have a deeper sense of the spaces I can command. I don’t want to over-rely on technical skill, but I do want to have a technical understanding of my medium. I want to be informed as deeply as possible by a knowledge of what color harmony means.

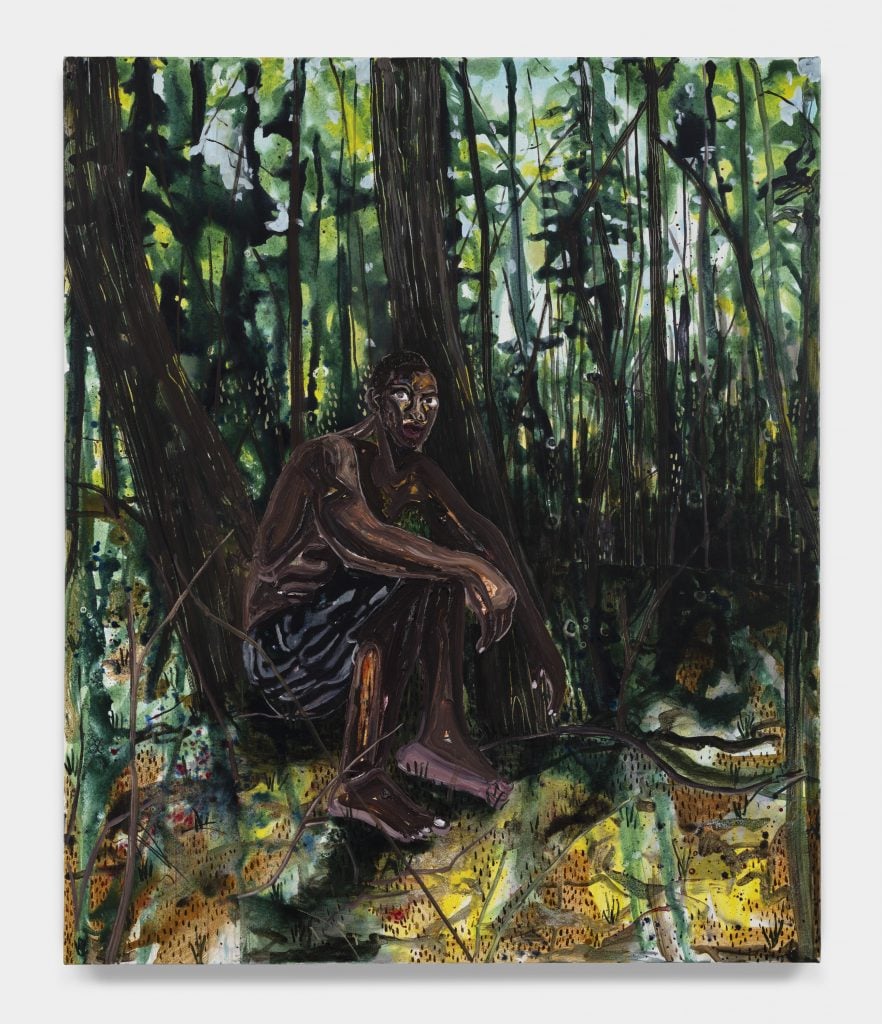

Ludovic Nkoth, Hot Feet (2022). Photo: © Ludovic Nkoth.

What tools do you enjoy working with most?

Mostly paint brushes, knives, and forks to scratch into paint. However, lately I’ve been using a broomstick to build up my underpainting. Ed Clark used to use janitorial broomsticks, partly as a way to think about the commonalities between the kind of labor that painters and custodians do. Both work with brushes. But with a paintbrush, I have to be this close to the canvas. The broomstick keeps me further back and lets me become a bit more subtracted. It pushes me to do something different. I like the element of chance in that process. I want to leave space for discovery, and to make “mistakes” that can be productive.

Do you have any studio assistants?

I don’t have any assistants right now, partly because I’m enjoying figuring out on my own what I need to do. But while I was working on the Pond Society show, I did work with a young artist who helped quite a bit. I make lots of sketches, often on an iPad, and she helped me trace those drawings onto canvas, so I could go in with an imprint already made. Now, in Paris, I’m working alone again. But that could change when I get back to New York. I may just need someone to help me mix paints. That would take a lot off my plate.

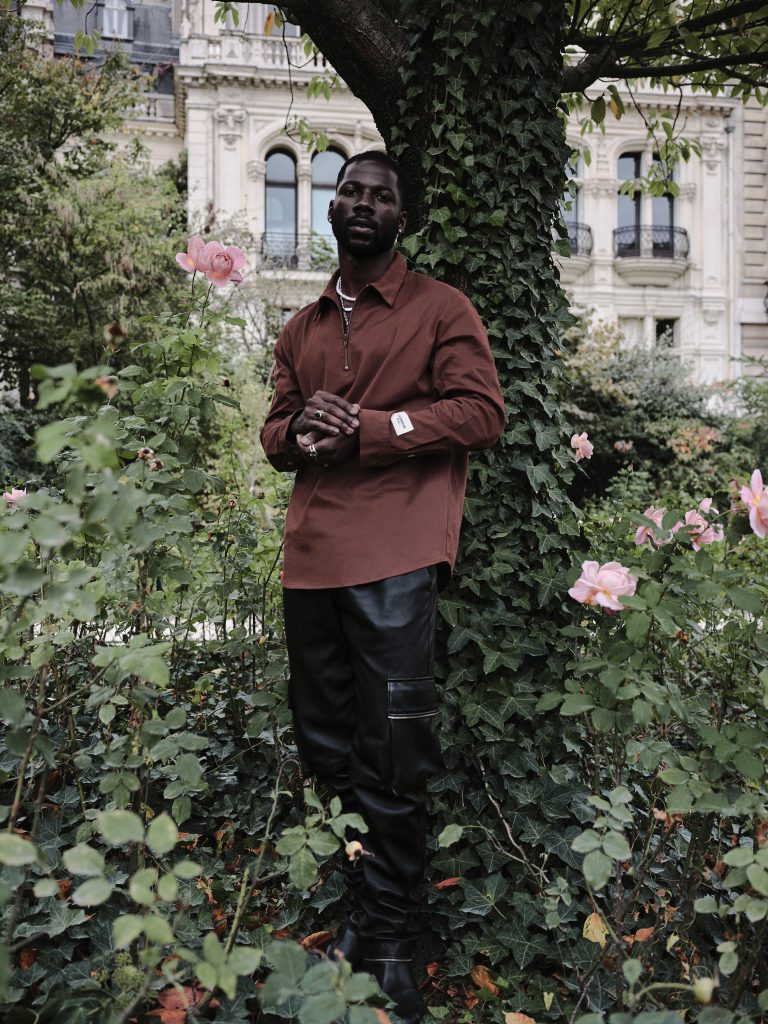

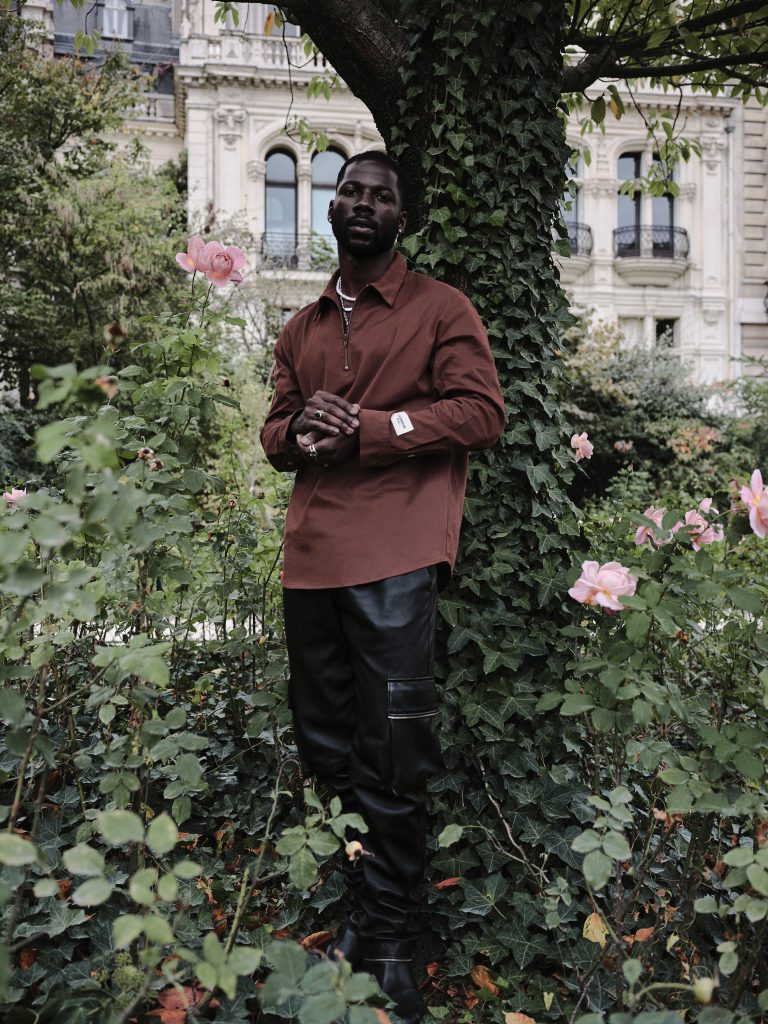

Ludovic Nkoth. Photo: Kargina Ksenia.

How many hours do you typically spend in the studio?

I love long studio hours. I’m almost like a hermit—I’m always in the studio. I try to keep myself from going in before 1 p.m. so that I can have a life outside. Generally, I spend the first three hours feeling the energy of the space, and I prefer to paint after sun down. I love the creative energy of the night. I’m not sure how to explain this, but the focus I’m able to tap into with the presence of the moon feels magical at times.

When you feel stuck, what do you do to get unstuck?

A number of things. Sometimes, I’ll go a few days without visiting the studio so I can refresh my connection to the work. And conversations are really important. I invite people over to bring their own lives and viewpoints into my work, and perspectives I cannot see on my own. Dante Cannatella is an artist and friend I met at Hunter and we understand one another’s way of working. We can anticipate what the other is going to do.

While I was working on a show I had with Massimo de Carlo in London in April, I was trying to figure out a complex conceptual frame, and Dante came into the studio and said, “You’re overthinking it, this whole process. You already know what to do. You have the skills to make these. Allow it to flow the way it always flows.” It was amazing. From that, I was able to move forward. It’s like that with Dante. He suggests something, and it unlocks five more paintings.