Art & Exhibitions

A New Show Spotlights Long-Overlooked Artist Luis Caballero

The late artist's drawings balanced queer tenderness with religious violence.

Though highly fêted in his native Latin America and adopted by France, the late Colombian artist Luis Caballero (1943–95) has remained woefully neglected in the wider art world. Following his untimely death from HIV/AIDS, Caballero’s auction market peaked in the 1990s, with sale prices averaging around $28,000 to $30,000. Today, his works are selling for up to $90,000.

Despite this uptick, a recent exhibition at Cecilia Brunson Projects in London was his first solo show in the U.K. Curated by Daniel Malarkey, it marked a potential turning point for the artist’s legacy, particularly as last year Tate acquired an untitled 1985 painting that was of similar style and scale to those on display at the gallery. At long last, it seems, Caballero is getting his due and finding a new generation of admirers.

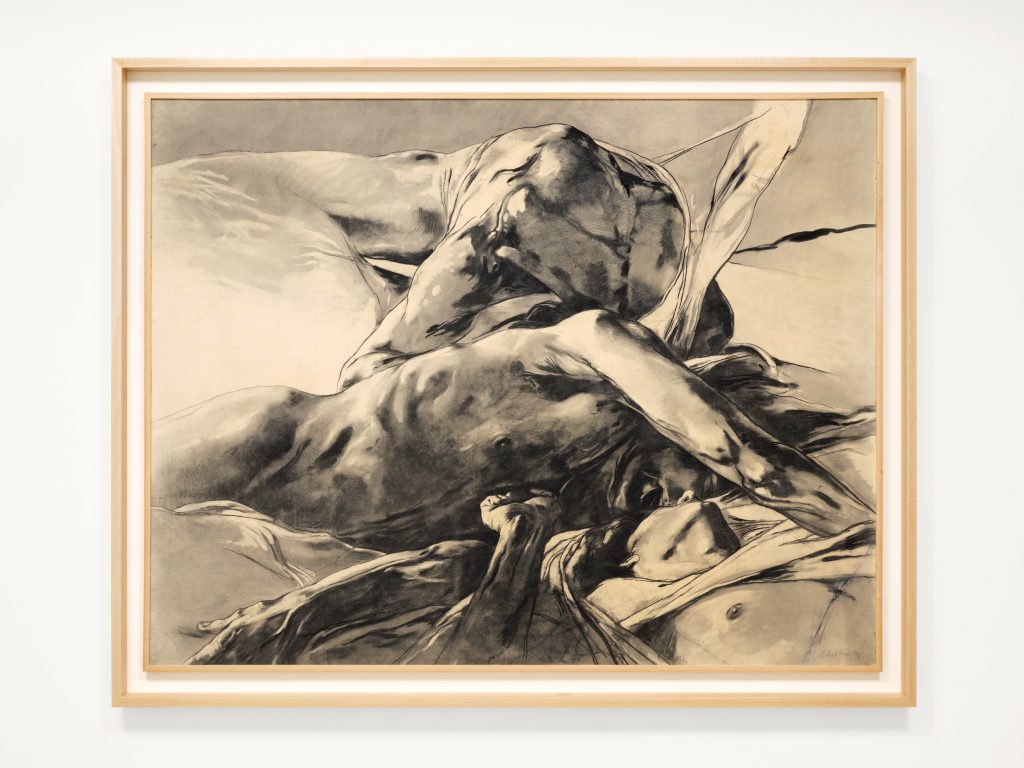

In the Cecilia Brunson show, which closed February 10, the artist’s works on paper, mounted on canvas, are a testament to his extraordinary control as a draughtsman. Charcoal is transformed into a nimble, fluid material conveying texture and sensation with an astonishing degree of precision. In a drawing from 1979 (untitled, as are all the works), two horizontal male bodies fill the frame. A sheet drapes one’s shoulder like a shroud. Are they in a state of post-coital exhaustion, or some other, more ominous form of abandon?

Installation view of Untitled (1979) in “Luis Caballero: A deliberate defiance,” curated by Daniel Malarkey at Cecilia Brunson Projects. Photo: Eva Herzog, courtesy of Cecilia Brunson Projects.

As in many of Caballero’s works, the faces of his subjects are obscured, turned away from the viewer in some unknowable compact of secrecy or shame. Instead, we’re left to divine a whole untold personal history through the surface of naked flesh. We see light gleaming off the hip bone of the central, horizontal figure and the curve of his jawbone. The second figure, chin glancing the other’s thigh, has his arm outstretched to the viewer. Is this supplication or surrender? An anonymous, third hand enters the frame, tendons quickening. We see his fingers push into the other’s arm with such physical force that the body could be your own, seized and caressed.

Caballero wanted to eliminate the distance between the canvas and the viewer. He conceived of the act of drawing itself as an erotic encounter. In an interview (originally in French) with Ramiro Ramirez, Caballero explained: “Desire pushes us to go ever further, and to a large extent, erotic desire makes me paint […] I believe that erotic desire is the promise of a pleasure greater than the pleasure itself and that desire is always reborn because the great pleasure never arrives.”

There’s a tension, felt between every line of these drawings, between sensuality and violence. This wasn’t just the stuff of art for Caballero, but lived experience. Growing up gay in 1950s Colombia, he was marked by a society dominated both by the oppressive influence of the Roman Catholic church and the decade-long civil war known as “La Violencia.”

“In the hands of the Catholic Church,” Caballero commented, “painting becomes a poisoned hook. It uses sensuality to seduce you—in order to destroy your sensuality.”

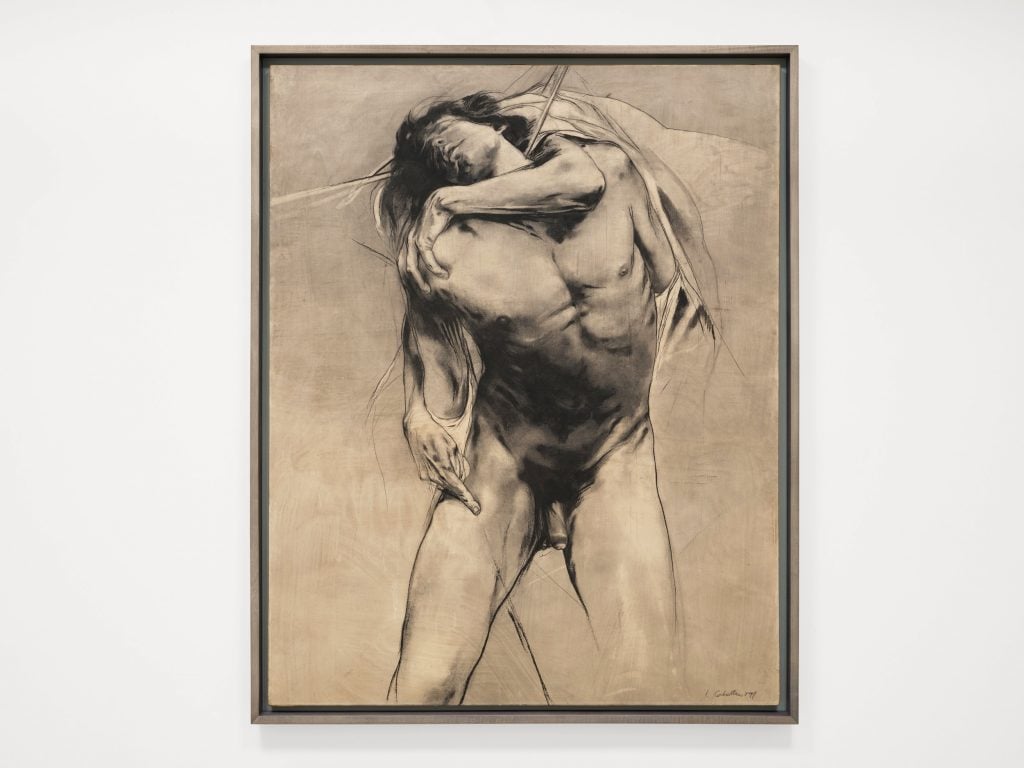

Installation view of Untitled (1982) in “Luis Caballero: A deliberate defiance,” curated by Daniel Malarkey at Cecilia Brunson Projects. Photo: Eva Herzog, courtesy of Cecilia Brunson Projects.

Motifs of religious suffering and ecstasy abound. Faces contort like Bernini’s sculptures. Arrows pinion flesh in a dramatic restaging of Saint Sebastian’s agonies. In one of the show’s most stark and arresting works, created in 1982, another undressed male body is shown suspended from the top of the canvas like an inverted crucifix. The line work is so dense and darkly described that it forces the viewer to bring their face close to the paper, their nose to the subject’s midriff and exposed genitals. Another anonymous hand digs into the flesh of the figure’s elongated, Christ-like thigh creating an image charged with menacing heat.

A curious image of seduction plays out in another drawing. A lean, long-haired youth is clasped from behind by a stranger. A finger points into the flesh of his leg like an accusation. The full lips and blurred expression of the object of desire conceal the nature of his feelings; another mystery of the body described, but left intact, by Caballero’s hand. (The artist was hostile to the idea of over-interpretation, once remarking that “a visual work needs no explanation and, if it is good, transcends all explanation.”)

Luis Caballero, Untitled (1979). Photo: Eva Herzog, courtesy of Cecilia Brunson Projects.

It is possible to place Caballero within a lineage of 20th-century gay male artists, all from conservative Catholic backgrounds, who created a subversive queer iconography, from Warhol’s pantheon of alternative saints to Mapplethorpe’s ritualized objectification of the male form. Francis Bacon perhaps remains closest to Caballero’s sensibility, with his claustrophobic theaters of bodily sensation, his smeared faces.

Yet where Bacon invokes a curdled and menacing sense of camp, Caballero substitutes something closer to devotion. His canvases are a form of worship, full of pain and longing—an attempt to transfigure the flesh into a new, beguiling form. As Malarkey observed, “Caballero is important to queer art history, Latin American art history, French art history” and, as new displays of his work prove, to art history full stop.