Art World

How Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s Revelatory Tate Britain Retrospective Shakes the Institution Out of Its Comfort Zone

The artist's motley crew of Black figures push the tradition of portraiture to new heights.

The artist's motley crew of Black figures push the tradition of portraiture to new heights.

Aindrea Emelife

After leaving Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s blockbuster mid-career Tate Britain retrospective, “Fly In League With The Night,” I rushed to post my thoughts about the show on Instagram. My own impassioned views were swiftly swallowed by others, as the often-touted “art-world darling” met almost unrelenting praise from critics.

Indeed, this is the exhibition we needed. We needed to see Black people—Black joy, angst, trouble, and all its complexities. We needed painting that hits at the soul like this.

For all its merits in contributing to depictions of Black people in art, and the poignancy of filling Tate Britain with proud Black figures, the exhibition cements how Yiadom-Boakye triumphs as a figurative painter, irrespective of her chosen subject.

The works—which span almost two decades, including recent pictures made during lockdown—investigate the tenets of chiaroscuro and the luxuriating melancholy and intimacy of darkness. There is a troubled agitation of Francisco Goya’s “Black Paintings,” shown best in the dastardly charm and oneiric atmosphere of First (2003), a work from Yiadom-Boakye’s Royal Academy degree show. This is resisted by the quiet theater of Degas in The Woman That Watches (2015) a tightly composed image of a woman voyeuristically peering through a pair of binoculars.

The artist also pushes forward the tradition of oil painting, explored and well-represented in Tate’s 18th-century galleries, and shakes it out of its complacency.

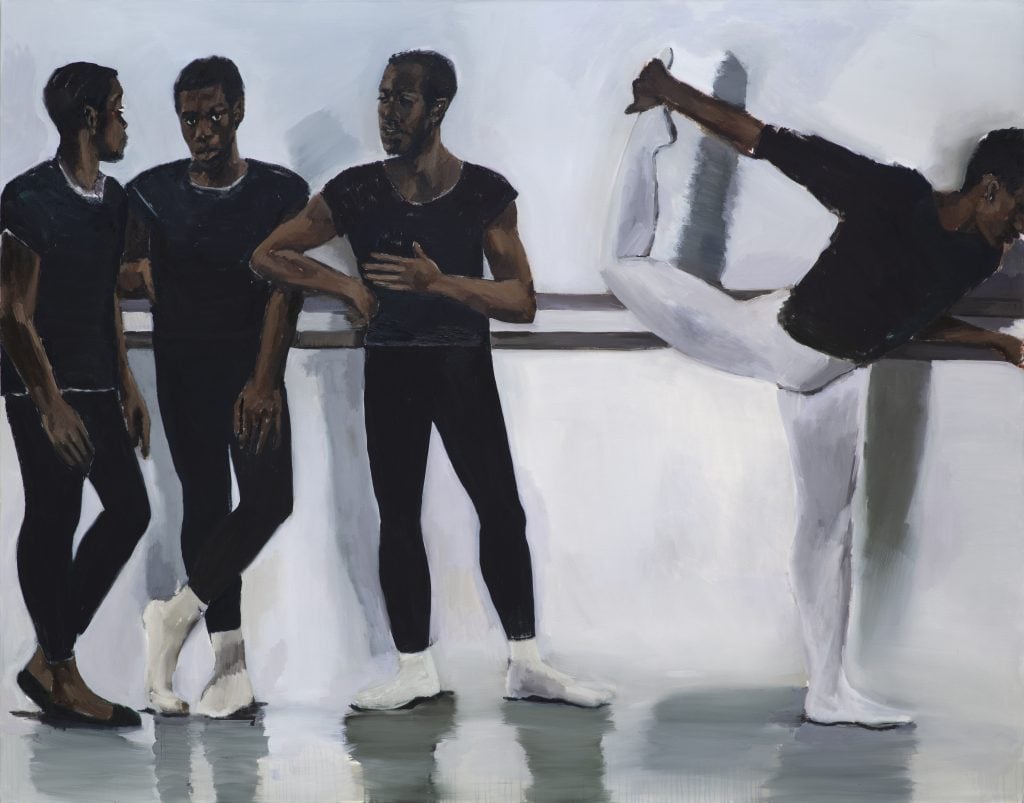

Lynette Yiadom-Boayke, A Concentration(2018). Carter Collection. ©Courtesy of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye.

The figures in the paintings are creations of Yiadom-Boakye’s imagination. There is a long history of artists imagining their sitters, allowing for portrayals to be more than just personal; rather, universal, and timeless. Of these historically imagined sitters, how many had skin like this? It is important to discuss what the “everywoman” looks like in our imaginations, as much as in real life. What do we see when we close our eyes? What does Yiadom-Boakye see?

The display, achronological and free of exhibition texts, works surprisingly well. Yiadom-Boakye’s ideas are distilled on canvas and then they run free. Black figures have suffered too much basic or generalized historization at the hands of blind, or ill-nuanced, art scholarship. The exhibition encourages you to see before you are told. You are sent forward without preconceived notions—in fact, breaking down stereotypes starts here.

“Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Fly In League With The Night” at Tate Britain 2020. Photo: Tate. (Seraphina Neville).

I must rebut those who critique her characters for being illusory or supposedly monotonous. Modern depictions of Black people, especially this year, are often stressful and emotional. They do often tell real-life stories of protest and agency, depicting civil-rights campaigners or activists for Black Lives Matter. But as real are Yiadom-Boakye’s champagne-clinking men or cigarette-smoking babes. Following this proliferation of Black figuration, the artist offers a complete story. They are beings just being.

Yes, some of the eyes and teeth are sparkling white—but this is an owning of a caricature. Monumental works like Wrist Action (2010) and Bound Over To Keep Faith (2012) show the best of these porcelain smiles and eyes.

Yiadom-Boakye posits, in her writings in an adjacent room, that it is about saying that “we’ve always been here […] self-sufficient, outside of nightmares and imaginations.” More than placing Black people into the canon, the depictions are a reclaiming, perhaps using the language that stereotyped, satirized, and relegated them in the first place.

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, A Passion Like No Other (2012). Collection Lonti Ebers. ©Courtesy of Lynette Yiadom-Boakye.

Her subjects may not be actual people; but there is blood running through their veins, thoughts, ideas, emotions and afflictions under that paint. In A Passion Like No Other (2012), you are met with a lugubrious stare from a rugged face, framed with the drama of a Tudor cuff. He looks like a troubled character from a Jacobean revenge drama, shoved into the contemporary with fidgety, feverish, brushstroke palpitations. It’s an uncomfortable stare—are you drawn in?

Many of the portraits operate with this nail-biting energy. Despite this singularity in approach and subject, it is not hackneyed or repetitive—it is as full of life as my feet, which moved from painting to painting; anywhere but the door.

In general, the attention stealers are the single portrayals, but some groups triumph in their Dutch Golden Age grandiosity. So it is in An Education, where a group of suited men are captured, deep in an absorbing conversation or debate. A celebration of Black excellence shines through with the curious glare of Rembrandt’s Syndics of the Drapers’ Guild.

Where the Black figure is subordinate in paintings within the permanent Tate collection, Yiadom-Boakye makes them extraordinary. We celebrate spirited joy as young girls play on the beach in Condor and the Mole (2011), and there is liberty in Black male ballerinas chatting and stretching on a barre in A Concentration (2018).

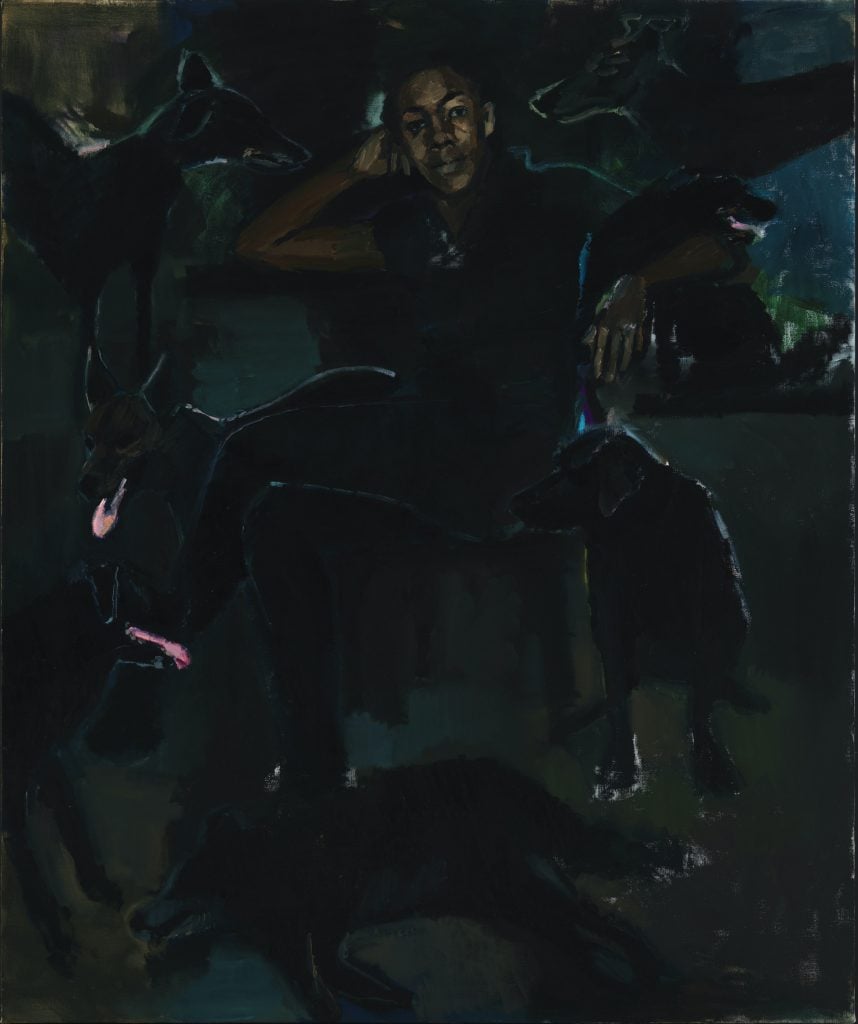

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, The Stygian Silk (2019). Courtesy the Artist, Corvi-Mora, London, and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Photo: Marcus Leith.

The exhibition ends with The Stygian Silk (2019), an affecting portrait of a reclining figure surrounded, Cerberus-like, by a pack of black dogs. The title takes its inspiration from the River Styx in Greek mythology, a site no stranger to torment and calamity. The symbolism of the black dogs—often associated with depression—are at odds to the hopefulness of the figure, which opens itself up to a contemporary reading in the context of this year. Perhaps the dogs are on their way out?

It is a curious shame that in a level below, where museum-goers would normally have their tea, cake, and exhibition debrief together in the Rex Whistler restaurant, they would usually do so in the company of Whistler’s frivolously racist display. With a glistening forthcoming exhibition program, including a triumphant intervention of the Otolith Group and an exploration of Caribbean British art set to shake things up in 2021, it is clear there is energy at Tate Britain. It must be channelled wisely.

“Lynette Yiadom-Boakye: Fly In League With The Night” is on view at Tate Britain through May 9, 2021.