People

Ballet Dancer-Turned-Artist Madeline Hollander Sees Choreography Where Others See Only Chaos. She’ll Help You See It, Too

Hollander’s new film at the Whitney Museum is unlike any other piece in her young career. It’s also the most revealing.

Hollander’s new film at the Whitney Museum is unlike any other piece in her young career. It’s also the most revealing.

Taylor Dafoe

Flatwing, the new film from Madeline Hollander on view now at the Whitney Museum of American Art, is ostensibly about dance. But technically, there is no dance in it.

This is often the case for the 35-year-old professional dancer-turned-artist. Where you and I see chaos, Hollander sees choreography: New York City traffic, flood mitigation systems, environmental change. The product of extensive research, her work transmutes the abstract patterns that govern our daily lives into elegant dance performances, heady gallery installations—and now, for the first time, film.

The 16-minute video at the Whitney documents Hollander’s search to find flatwings, a new breed of Polynesian field cricket that, due to genetic mutation, has lost the ability to chirp. For the insects, it’s both a gift and a curse: They are now essentially invisible to their predators—an acoustically oriented parasitic fly that once threatened to wipe out their entire population—but also invisible to their potential mates. The crickets’ ability to adapt is likely, ironically, to lead also to their extinction.

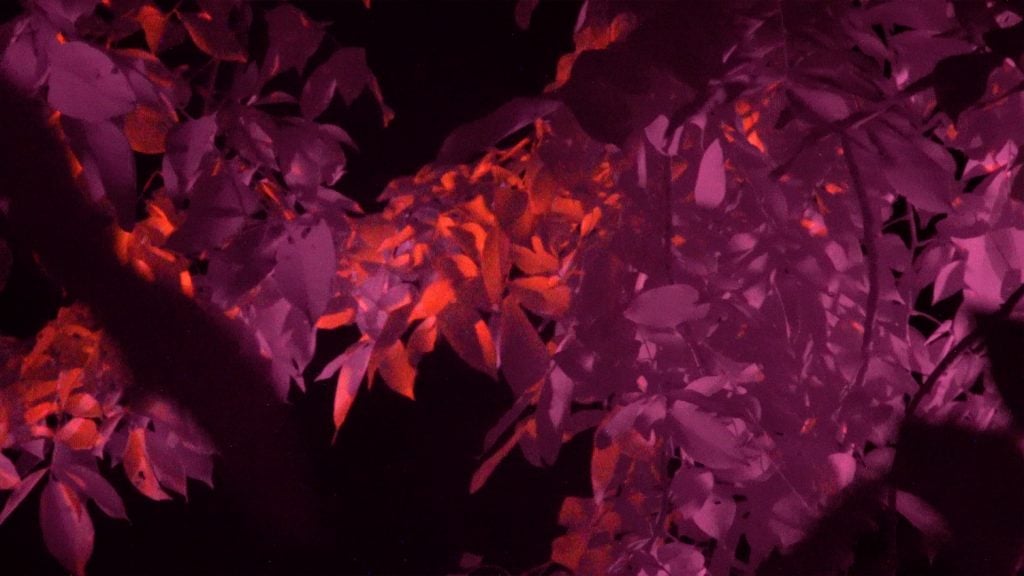

Film still from Madeline Hollander’s Flatwing (2019), Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. © Madeline Hollander.

Meanwhile, they continue their mating dance in the dark, silent, essentially hoping—by the grace of God or good luck—to crash into a partner.

In December 2018, Hollander more or less attempted to do the same thing. Wanting to study the crickets’ vestigial dance for a piece of choreography she was working on (more on that later), she trekked out to a rainforest on the Hawaiian island of Kauai for five nights with an infrared lamp soldered to a car battery and a camera strapped to her head, hoping to capture the little creatures in action.

What came out of the pilgrimage was hours and hours of shaky, Blair Witch-style footage— forest flora, random animals, the vacuous night sky. But no crickets.

The mission was, ultimately, a failure.

***

The artist did not set out to make an artwork in Kauai. She was conducting research—a meticulous behind-the-scenes process that constitutes an increasingly significant part of her practice.

Specifically, she was looking into crickets for New Max, her 2018 piece at New York’s Artist’s Institute in which a quartet of dancers performed a series of scripted movements until they raised the temperature in the room enough to activate four air conditioning units, at which point they’d stop moving. Once the A.C. went off, they’d begin again—and so on and so on.

Pondering heat and movement, the artist recalled a fun fact from her childhood in L.A.: that you can tell the temperature outside by counting the number of times a cricket chirps in 14 seconds, then adding 40. A few Googles later, she came across several articles about how Kauai’s nightscape had gone silent thanks to the rapid mutation of the chirping crickets, a process that took an alarmingly short amount of time—just 10 years, compared to normal evolutionary timelines that exist over centuries.

Madeline Hollander, New Max (2018), The Artist’s Institute, New York. Photo: Christopher Aque.

“This really struck me,” Hollander told me over video chat this month, tuning in from her home in L.A. “It felt like an alarm had gone off. Trying to imagine what a nightscape would feel like without that rhythm felt very ominous.”

That Hollander would be interested in the crickets makes sense. This biological anomaly at the margins of its own ecosystem, a harbinger of environmental calamity dancing in the dark: the creature symbolizes the intersection of micro-movement and macro systems at the heart of most of her work. She quickly became obsessed.

“If this evolutionary phenomenon could happen in 10 years, then perhaps this could be the only chance I would ever have to witness the evolution of a mating dance to unfold in my lifetime,” she said. “That stuck in my head.”

Some artists are bad at school because they’re good at art. Hollander excelled at both—and she’s well practiced in juggling the two.

Born and raised in L.A., the daughter of an artist (her mother) and a Hollywood visual effects supervisor (father), Hollander began dancing competitively at a young age, studying with the famed ballerina Yvonne Mounsey. Virtually every minute of her life when she wasn’t at school, including weekday lunches, she was at the dance studio.

After College at Barnard in New York, where she split time studying anthropology and dance, she was invited to join a Madrid company’s touring production of Swan Lake. For two years, she traveled around the globe performing the show. It was a dancer’s dream, but not a polymath’s: for Hollander, the 24/7 grind was frustrating.

Madeline Hollander, New Max (2018), The Artist’s Institute, New York. Photo: Christopher Aque.

“I had always split my life in two—there was the brain side and body side,” she said. “Being on tour for two years felt—it was an incredible experience, I just wasn’t as creatively [fulfilled]. I was filling up notebooks of ideas, things I wanted to do, and just wasn’t executing them.”

She returned to New York, hoping to dance part-time while pursuing other creative outlets. This was a “big turning point,” she said. “I knew I needed to begin fusing these two passions together.”

It didn’t go as planned. During the last performance of the Swan Lake tour, it turns out, Hollander had broken her foot onstage. She found out weeks later after an MRI in New York. “I went dancing into the MRI and [came] out with a cast,” she recalled.

After reading about the crickets in 2018, Hollander’s next step was a phone call with evolutionary biologist Marlene Zuk, the leading expert on flatwings. A recording of their chat is the soundtrack to the Whitney film.

The conversation is as funny as it is awkward: the artist posits a poetic interpretation of the cricket’s ritual and the biologist counters matter-of-factly with research to debunk it. Over and over again, artsy whataboutism rams up against scientific reason. It’s as if they’re having two separate conversations.

If research makes up nearly half of Hollander’s practice, then this part is the other component: arguing with people outside her field to convince them to help her.

“That’s a very typical conversation that I face,” Hollander said of her chat with Zuk. “There’s these two worlds and two vocabularies and two very different processes clashing with each other continuously because we have different goals. One’s a business and I’m an artist, or one’s a scientist and I’m a choreographer. I’m really fascinated by the different architectures of those dynamics.”

MadelineHollander, Heads/Tails (2020), Bortolami Gallery, New York. Photo: Kristian Laudrup.

Prior to her 2020 show at Bortolami, the artist spent two years going back and forth with the New York Department of Transportation trying to acquire data about local traffic patterns and drivers’ habits. She used it to sync hundreds of used car head- and tail-lights installed on the gallery walls with a nearby traffic light. When cars would slow to a stop before a red outside, the exhibition space inside would begin to glow.

It was a simple and elegant execution of a process that, to hear Hollander tell it, was anything but.

“What becomes absurd for one person becomes very reasonable for the other,” she said of the frustrating conversations behind that work. “More and more, I feel that those limits, they’re not arbitrary; they’re very instilled in our culture. And when you can break through, all of a sudden the piece becomes bigger than the sum of its parts.”

Although Hollander didn’t know it at the time, the foot injury essentially ended her professional dancing career. When she finally healed months later, she was offered roles in other companies, but by that point, her life as an artist was percolating. Around 2012, she had begun choreographing her own pieces. But unlike most choreographers, who draw from a time-tested inventory of movements, Hollander pulled from a library of her own making.

The gesture archive, as she referred to it, was a collection of short videos documenting everyday micro-movements, many necessitated by new technology—the wheeling thumbs of a Blackberry user, for example, or the knuckle-crack that comes after long spells of keyboard typing. “I was very interested in how technology was trying to accommodate the kinetics of the body,” she explained.

Hollander’s gestures don’t look like the stuff of dance. But when strung together, they become poetic.

Film still from Madeline Hollander’s Flatwing (2019), Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. © Madeline Hollander.

It didn’t take long after she began to pursue choreography for her career in the art world to evolve rapidly. She earned a place in the prestigious Skowhegan residency, then got her MFA at Bard. Now, with several gallery shows, a Whitney Biennial project, and a solo museum show under her belt, she’s as in demand as an artist of her ilk can be. And not just in the art world—she also worked as a choreography consultant on Jordan Peele’s 2019 film Us and Christopher Nolan’s 2020 movie Tenet, with more film projects in the works.

Hollander still dances almost every day. “It’s really a part of my practice,” she said. “All of my ideas come from that morning ritual.”

Despite her best efforts, Hollander never found the Kauai crickets, never witnessed their dance.

It’s not hard to see why. An artist traipsing through a dark rainforest with some jury-rigged equipment to locate a tiny creature that is notoriously hard to locate, even for scientists—the whole exercise reads, in retrospect, as absurd.

But then again, that may have been the point. As Whitney curator Chrissie Iles, who co-organized the show, noted, “The absurdity of that search tells us something about [what it means to be] human—thrashing around in the dark to find meaning and a solution to something very existential.”

Hollander didn’t look at the footage for a long time after she got home. “I was so disappointed,” she recalled, still a little heartbroken. When she finally did press play, some six months later, she came to a conclusion similar to Iles’s. She realized that, in missing the insects, she had managed to document something more elusive—something personal.

Indeed, Flatwing is unlike any other piece in Hollander’s still-young career. But it is perhaps the most revealing of the way she thinks.

“For me, this piece really functions as—not a self-portrait of me personally, but of my practice,” the artist said. “This same type of path of me searching in a futile, stubborn, desperate, hopeful blindness, stumbling around—that’s just what I do before I actually hit the idea that eventually gets distilled into a performance or an installation.”

“Madeline Hollander: Flatwing” is on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art through August 8, 2021.