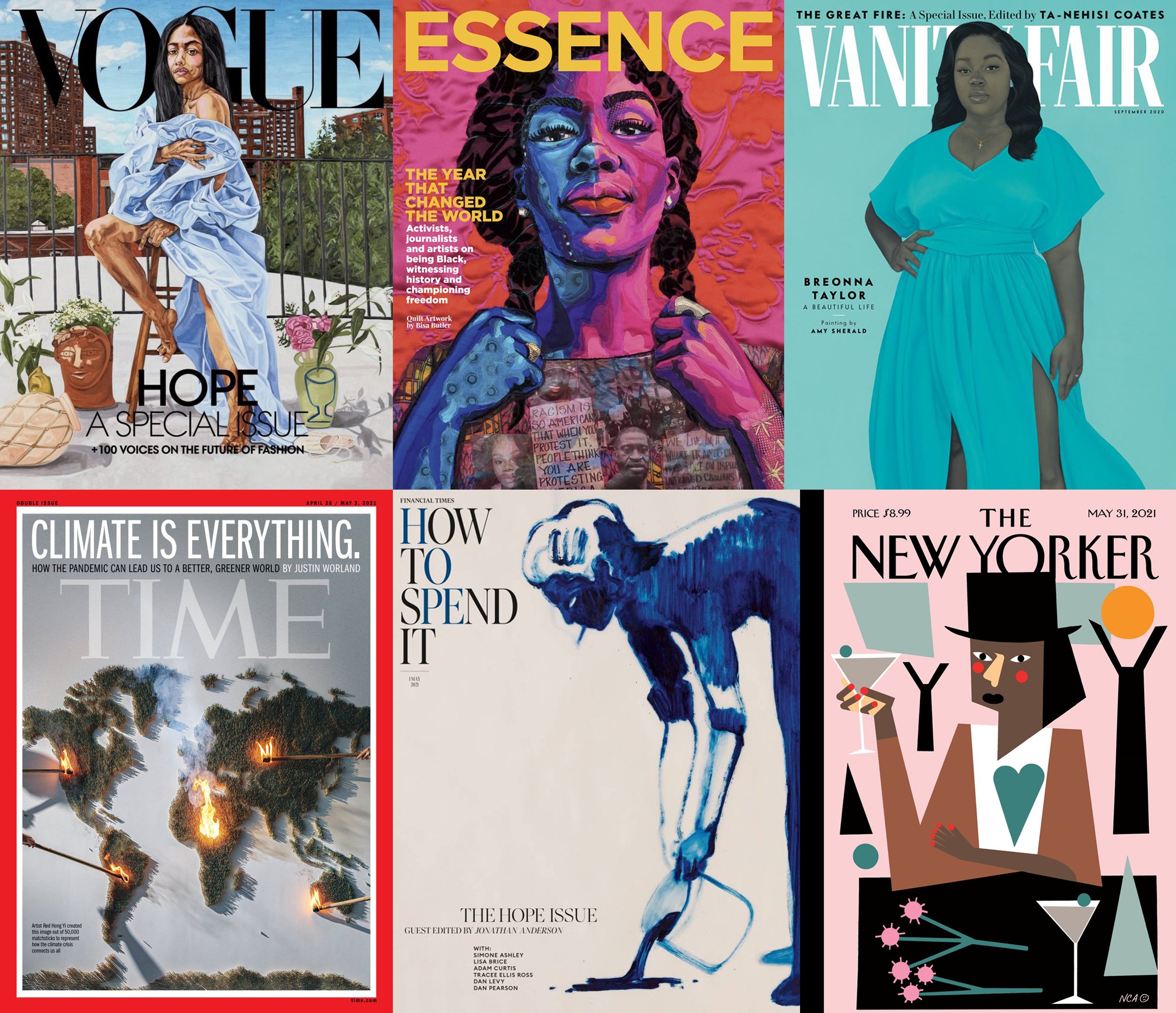

Last summer, after weeks of protests precipitated by the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, two of the country’s most recognizable magazines used their covers to make a statement. And they each turned to artists—not photographers—to do it.

For their respective September issues, which came out within days of each other, Vanity Fair commissioned painter Amy Sherald to make a defiant portrait of Taylor, while Vogue tapped artists Kerry James Marshall and Jordan Casteel to make their own exultant paintings of Black women.

These images were a far cry from the tired Annie Leibovitz photographs usually found on the front of these magazines. And at a time when magazine covers routinely foment here-today-gone-tomorrow Twitter wars, these issues seemed to get people talking for all the right reasons.

That these covers were done by artists was a big reason why, says Mark Guiducci, Vogue’s creative editorial director who helped plan and produce the September issue. He and his team had actually planned to commission a painted portrait for the issue prior to the protests—a practical decision more than anything else, given the difficulty of staging big-budget fashion shoots during the pandemic. But as a nationwide racial reckoning played out, the notion of showcasing a model or celebrity on the cover suddenly felt out of touch.

Kerry James Marshall’s cover for Vogue. Courtesy of Vogue.

“How could one personality encapsulate that moment of pain, of pandemic, of reckoning?” Guiducci said. So they turned to Marshall and Casteel, and gave both artists carte blanche—a privilege rarely bestowed by the magazine.

“That’s why you go to an artist,” he said. “They give you the vocabulary to see the world in a new way. That’s powerful.”

Vanity Fair, meanwhile, knew it wanted to celebrate the life of Taylor in its September issue. But republishing one of the few pictures of Taylor circulating online at the time didn’t seem to do her justice, said Kira Pollack, Vanity Fair’s creative director.

“In order to make something truly transcendent, we felt it was important to create a new image of Breonna,” Pollack said. “We knew that Amy’s voice, and the intention and care she brings to her work, would be exactly right for such a powerful portrait at such a sensitive moment.”

Rihanna by Lorna Simpson for Essence Magazine, 2020. Courtesy of Essence.

Vogue and Vanity Fair aren’t the only major magazines to turn to artists for their covers in recent months. Essence put works by Lorna Simpson and Bisa Butler on its covers this year; issues of the New Yorker featured paintings by Wayne Thiebaud and Nina Chanel Abney; and a 2020 edition of O Magazine was illustrated with a painting by artist Alexis Franklin, marking the first time in its history that a picture of Oprah wasn’t on the publication’s cover.

Of course, magazines have run artworks on their covers for as long as they’ve existed, and many famous artists—from Salvador Dalí to Robert Rauschenberg to John Currin—have had their turn on the newsstand. What is novel today is the prevalence of this strategy to mark the occasion of important issues. What may have started as a response to the limitations of lockdowns has become the way mainstream publications signal that they really want people to pay attention.

“In a culture that is overwhelmed by visual media,” Guiducci said, “the idea of painting, in particular, is quite resonant. It doesn’t feel like something that is made quickly or easily or digitally, and that is impactful.”

Alexis Franklin drew this portrait of Breonna Taylor for Oprah magazine. Courtesy of Oprah magazine.

D.W. Pine, the creative director of Time, noted that the role of the magazine cover has evolved in recent years. Its function, he said, is not to “tell the news anymore”—that job has been supplanted by social media. The cover’s purpose today is more about the conveyance of emotion than information.

A cover today says, “I can’t really tell you what happened, but I can kind of get you to the why, and I can definitely get you to think about it,” Pine said. “Artists help us do that.”

Time has probably been the biggest player in this trend, having commissioned artists such as Red Hong Yi and Charly Palmer, among many others, for recent high-profile editions. Time‘s “Vote” issue, pegged to the 2020 election, featured an illustration by Shepard Fairey, for instance, while a special pandemic report was accompanied by a photo of a JR installation. (Both artists have created multiple covers for the magazine.) Its April 2021 “Future of Business” issue featured a cover by Beeple, hot off turning heads with his $69 million sale at Christie’s.

In Time’s case, the draw for artists isn’t necessarily the paycheck. Every cover artist, regardless of his or her stature, has been paid the same fee for years. (Pine did note, however, that some recently resurfaced Andy Warhol invoices from the ‘70s took him by surprise: “It was a lot more than what we pay now!”) What Time can offer artists instead is exposure: Its weekly readership tops 60 million.

Conversely, what artists grant the magazine is “soul,” as Pine put it. “This past year we needed to provide more meaning and a feeling and a soul to the stories that were presented to all of us,” he said. “All of us were reacting to these stories each week. That’s where it’s important to turn it over to the perspective of an artist.”

The cover of Time magazine’s June 15, 2020, issue, featuring Titus Kaphar’s painting Analogous Colors. Courtesy of Time.

One recent issue illustrates this “soul” quotient in particular: Time‘s June 2020 “Protest“ edition, which featured a cover by Titus Kaphar.

Kaphar’s painting depicted a grieving Black mother holding a silhouette of her child—an effect the artist achieved by cutting into the canvas. It was a literal, legible expression of the losses so many have felt at the time.

“In her expression, I see the Black mothers who are unseen, and rendered helpless in this fury against their babies,” Kaphar wrote in a poem to accompany the cover. “As I listlessly wade through another cycle of violence against Black people, / I paint a Black mother… / eyes closed, / furrowed brow, / holding the contour of her loss.”

“He cuts the canvas out and shows what a mother’s loss is during this time,” said Pine. “That’s the meaning and the soul that we wanted to get at with everything that was going on.”