Art World

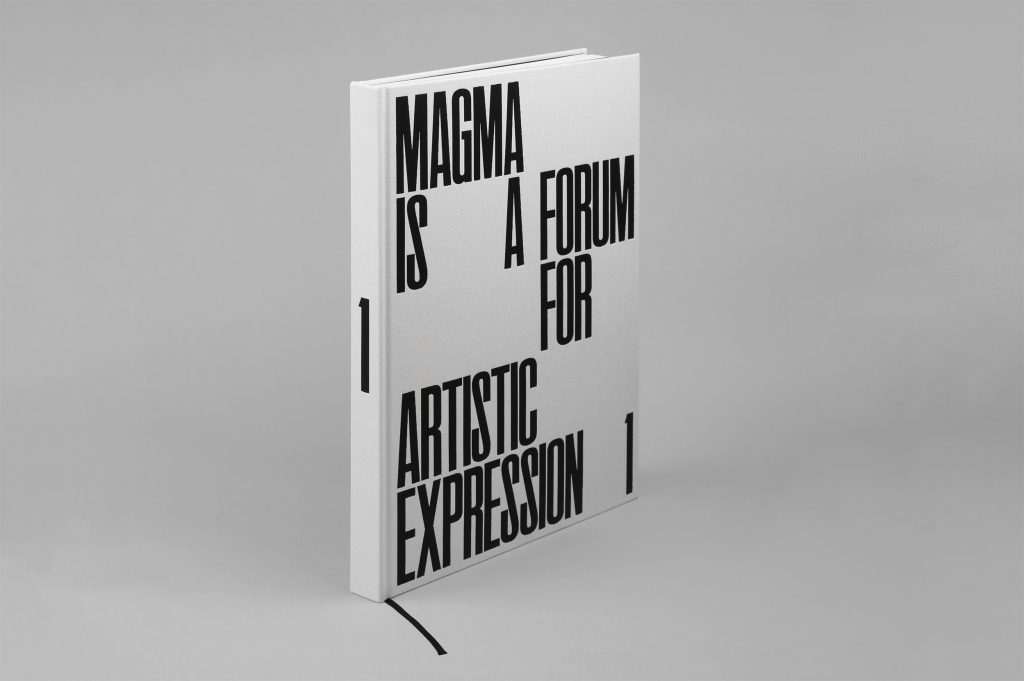

‘Magma,’ a New, Limited-Run Annual Featuring Original Works, Brings Artists and Writers Into Dialogue

The hardcover debut, sponsored by Bottega Veneta, showcases artists such as Lucas Arruda, Sophie Calle, and Agnès Varda.

The hardcover debut, sponsored by Bottega Veneta, showcases artists such as Lucas Arruda, Sophie Calle, and Agnès Varda.

Annie Armstrong

Print is dead, long live print. Magma, a new magazine in the style of a traditional revue d’art has hit the stands, with 18 artists (Sophie Calle, Lucas Arruda, and Tim Breuer among them) creating new work for its pages.

Limited to only 2,000 copies, the hardcover publication is now available for purchase online and at art book stores around the world for about $65. It’s a very high brow (and very French) take on art with swerves into poetry and literature as well. “It’s a response to a certain necessity,” said Magma editor-in-chief, Paul Olivennes. “There is so much discourse created about artists, about writers, and their work, but so little work where artists and writers can have freedom.”

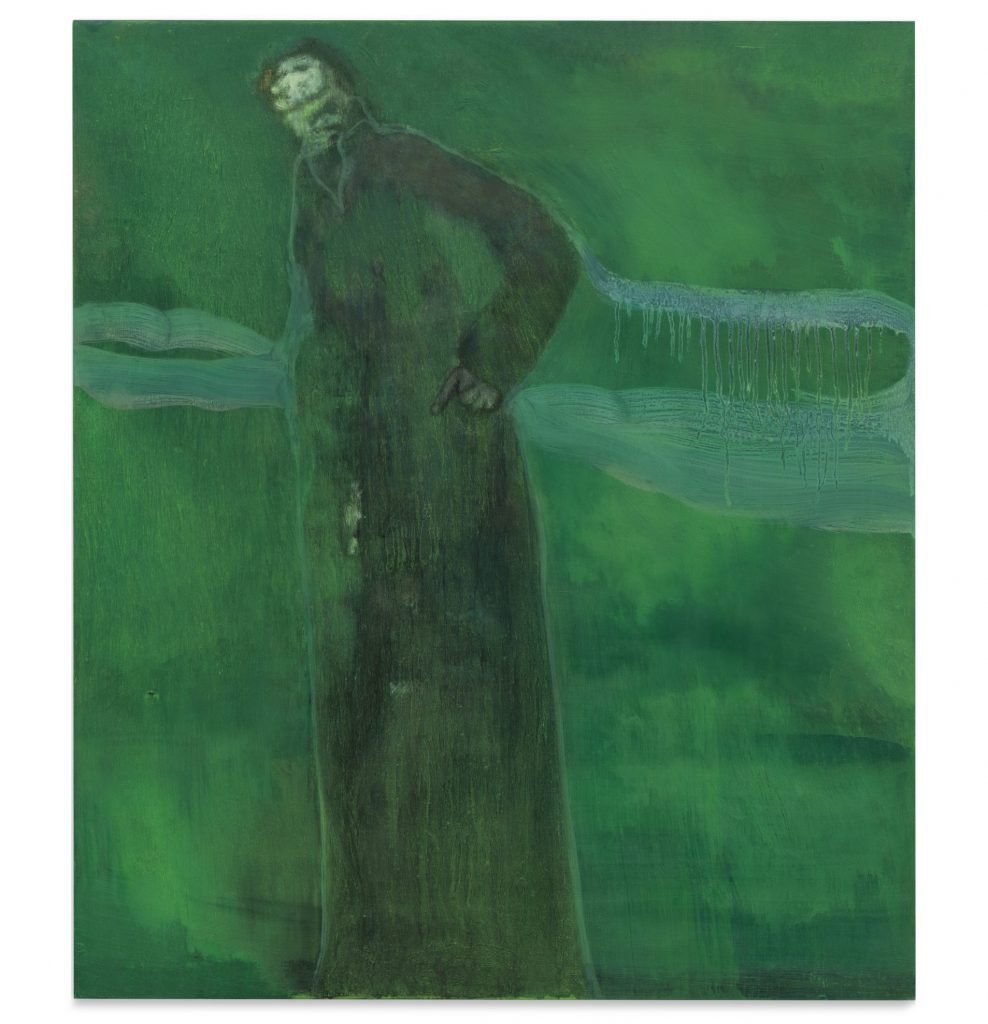

Tim Breuer, Watcher (2022). Courtesy of the artist.

Although an independent publication, Magma is sponsored by Bottega Veneta. Intellectual art endeavors have become increasingly central to creative director Matthieu Blazy’s broader vision.

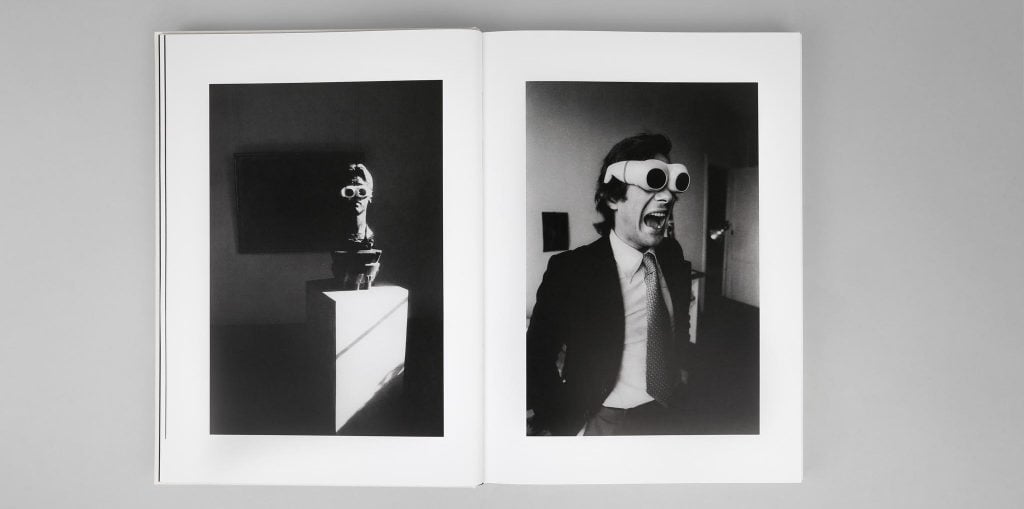

One standout Magma feature includes an unpublished 1976 text by the late filmmaker Agnès Varda, ruminating on the photography of Claude Nori. Said Olivennes, “Varda and Nori lived in the same building on Rue Daguerre in Paris. As a young photographer, Nori showed his neighbor and friend his images of the unusual journey of a pair of glasses shaped like legs, and Varda responded with this text. It is an encounter that means a lot to me.” On the following page, Lucas Arruda presents a painting that engages in dialogue with a poem by Edouard Glissant.

The filmmaker Agnes Varda weighs in on Claude Nori’s photos. Courtesy of Magma.

“Magma is about showing the work, not writing about it. For the reader, it should feel like a breath of fresh air,” explained Olivennes. “There’s no rubric, no theme. It’s about creating a rhythm – between colour and black and white images, between texts, between shorter and longer entries. The sequencing of the magazine should ensure that nobody gets bored.”

Hans Ulrich-Obrist writes in the magazine’s preface: “Magma brings worlds into contact with other worlds.” Olivennes further explained of the goal of the magazine, “We live in a world that has produced so much discourse about artists. Magma is the discourse of the artists themselves. We strip away mediation and create instead a direct encounter through which the viewer can experience their own, instinctive response to the work.”

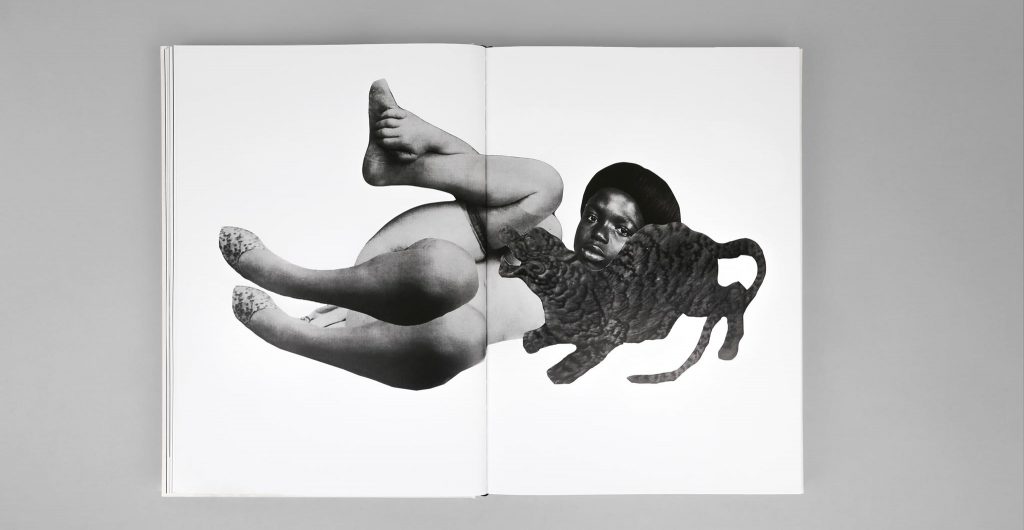

Frida Orupabo created striking photographic collages for the debut issue. Courtesy of Magma.

Olivennes adds, “I see my role more as that of a facilitator than curator. It was important to listen to the artists, their desires for collaboration and dialogue, and find the ways that they spoke to and resonated with one another.”

Overall, the goal of Magma is to uphold the legacy of other art publications like Georges Bataille’s Documents from 1929, Henri Matisse’s Verve, or early issues of Andy Warhol’s Interview. As Oliviennes put it, “It’s a response to a certain necessity. It’s connected to the age we live in, and the way we engage with literature and art.”

Andra Ursuța, Untitled (Record) (2023). Courtesy the artist, © 2023, Documents Editions

Magma makes sure some of that engagement goes beyond just flipping pages. Included in the first issue is some fascinating ephemera, such as an envelope containing poet René Char’s reproduced, hand-scrawled moving missive to his goddaughter. Later on, the reader will come to Romanian sculptor Andra Ursuța’s romantic ode rendered onto a static-laced, 45-RPM flexidisc printed on a vintage medical x-ray.

“In an era of technological reproducibility, Instagram, virtuality, and ephemerality,” Olivennes explains, “the goal was to give meaning back to the tangible object, to the artist’s gesture.”