Art & Exhibitions

Christian Jankowski’s Manifesta 11 Tries to Be Too Many Things at Once

Engagement with the practical world leads to navel-gazing.

Engagement with the practical world leads to navel-gazing.

Hili Perlson

On June 5, Switzerland became the first country in the world to hold a nationwide referendum on unconditional basic income. “Unconditional” here meaning that the basic sum provided monthly to all citizens should be sufficiently priced to allow a dignified existence and participation in public life. If there ever was a place where this could become a reality it’s here, a peaceful and affluent country in the heart of Europe—though not in the European Union—which takes pride in its model of direct democracy. Alas, the basic income proposal was voted down this past Sunday, with approximately 77 percent of those who had participated casting their ballot against it.

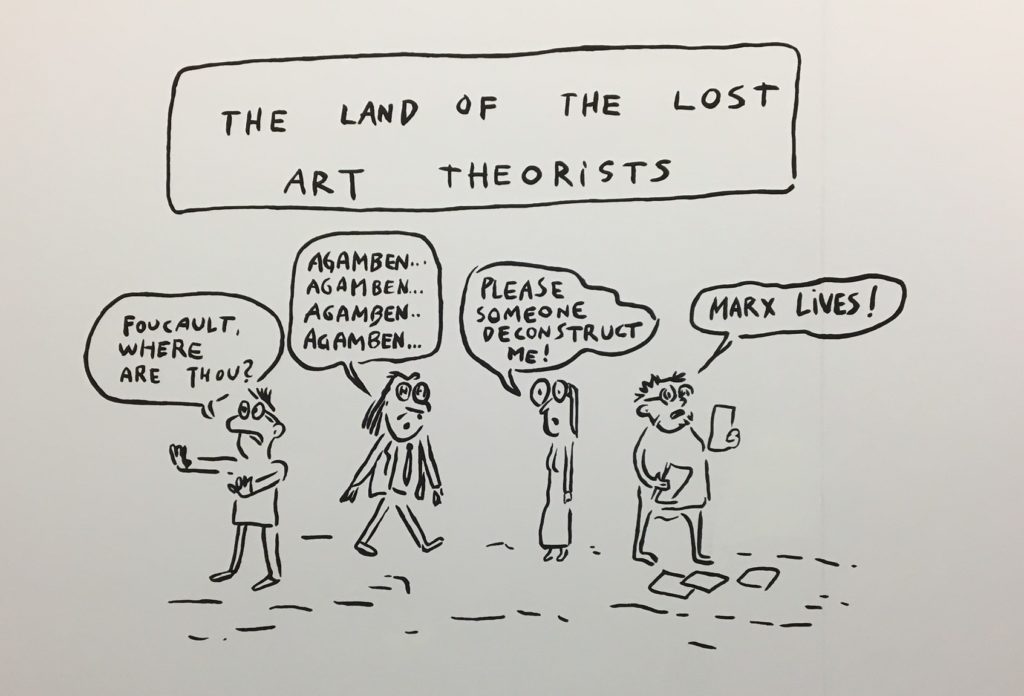

Related: Maurizio Cattelan Will Have Paralympics Athlete Ride Wheelchair on Water for Manifesta

This is the backdrop against which, five days after the referendum, the 11th edition of the roving European biennial, Manifesta, opens to the public in Zurich, with the title “What people do for money.”

Maurizio Cattelan and Edith Wolf-Hunkeler. Courtesy of Manifesta 11

Curated by artist Christian Jankowski, the theme is broached by a series of 30 so-called “joint ventures” bringing artists to collaborate with professionals from all walks of life—literally, from pastor to sex worker.

Jankowski’s own practice often involves such interactions with professions external to the art world—the most famous being his film Casting Jesus (2011), where he asked members of the Vatican to jury a reality-show-like audition for the role, with actors performing tasks such as breaking bread. He is no stranger to giving away control of his work, either, and had invited German actress Nina Hoss to curate his retrospective in Berlin recently.

What happens when an artist with such a strongly recognizable practice wears the hat of the curator? As Jankowski admitted, “I tried to conceive an exhibition that I’d also like to be invited to myself,” while insisting that the biennial should not be seen as one big artwork by him.

But that’s up to the participating artists and only a handful of them managed to take the rules of the game created by Jankowski and carry them forth, away from his signature witticism. Interestingly, it was often the younger and least known names on the roster. That is not to say that having a biennial full of rib-ticklers is necessarily wrong, but when the stated goal is to create interactions between artists and people working as doctors, teachers, therapists, cooks, policemen, scientists, athletes and so on, jest can feel like exoticism—or worse, render the work of artists irrelevant.

An employee at the Pak Hyatt wearing Franz Erhard Walthers “Half Vest” for Manifesta 11. Photo courtesy of the author

Among the most delightful ventures is the work by Franz Erhard Walther, who has collaborated with a textile producer on bright orange “half-vests” now worn by staff at the Park Hyatt hotel. Walther, a pioneer of conceptual art and performance, is known for the minimalistic fabric pieces that he integrates himself into by means of wearable parts. For the staff—who seemed genuinely excited and honored to don the new addition to their uniform when I visited the hotel lobby, which is filled with some of the worst works by Sol LeWitt I’ve ever seen (unrelated to Manifesta)—he created half a vest with one sleeve using cotton which is less dense than the one in his artworks and more functional, yet still maintains its sculptural character.

An important and utterly successful element of Manifesta 11 is that each commissioned work exists in three parts: one is displayed at one of the main venues; another at a satellite location in Zurich where a work is installed, activated, or performed; and lastly, as a short documentary, created by film students and screened every evening at the Pavilion of Reflections, a floating construction on lake Zurich.

Torbjørn Rødland and Dr. Danielle Heller Fontana, Médecin-dentist.

Courtesy of Manifesta 11

So for example we learn from the film that some of the works by Norwegian artist Torbjørn Rødland, who had collaborated with dentist Danielle Heller Fontana to create images that play on the disturbing symbolism ascribed to teeth in dreams, were removed by the dentist due to patients’ complaints.

Perhaps it’s no coincidence that several artists chose to collaborate with professionals from the world of medicine, health, and even wellness, including Jon Rafman, who shows work slightly too similar to the one presented only last week at the 9th Berlin Biennale. After all, Switzerland was historically the land of holistic Sanatoria, where tuberculosis patients came to recover and writers such as Thomas Mann and Herman Hesse came to replenish. French author Michel Houellebecq opted for conventional Western medicine and collaborated with a specialist to create a portrait of the artist from (expensive) medical data.

In the exhibition venue the Helmhaus, MRI and ultrasound imaging of Houellebecq’s skull, hand, and arteries are on display. The symbolism of creating a portrait from the writer’s head and hand collides with the reality that Houellebecq is a very heavy smoker, his hand tremendously nicotine-stained, and his arteries, as the doctor points out in the show’s catalogue, not looking very good. At the satellite location—a fancy private clinic with a pleasantly scented lobby—viewers can pick up color printouts of Houellebecq’s tests, and glean whatever they can from them.

Sexual and mental health also play a role for several projects, with one standout example being Andrea Éva Györi’s collaboration with a sexologist to explore the female orgasm. The list of well-conceived collaborations is long. And at times, humor—à la Jankowski—makes for grand gestures, like Mike Bouchet’s blocks of excrements, or Maurizio Cattelan’s idea of a performance consisting of a paralympic athlete riding her wheelchair on water, which may or may not happen.

Smaller gestures also make an impact, for example the work by German artist and filmmaker Marco Schmitt, who collaborated with Zurich police to create the film Exterminating Badges, which takes its cue from Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel (1962) and switches Buñuel’s bourgeois guests trapped at a dinner party (which they cannot seem to find the will to leave) with policemen inexplicably trapped in Zurich’s crime museum.

Marco Schmitt, still from Exterminating Badges 2016. Courtesy of Manifesta 11

In the main exhibition venues, the Helmhaus and the Löwenbräu, a historical exhibition is presented alongside elements from commissioned joint ventures. Co-curated by Jankowski and Francesca Gavin, the historical show is mounted on free-standing structures, which allows viewers to walk around the works. This is a very dense addition to the biennial that positions artworks in thematic and very didactic clusters to demonstrate examples from the past 50 years of artists who integrate professionals or cast themselves in new professions.

So we encounter Sophie Calle’s 1980 project The Detective or Jonathan Monk’s This Painting Should Be Installed by an Accountant (2011). The curators being who they are, there are also a lot of references to subcultures, and even hilarious non-art inclusions, like the Calendario Romano, a calendar known to certain insiders featuring Roman priests from the Vatican, photographed by Piero Pazzi, who all happen to be extremely attractive young men. It’s available to order online for €10.

But this is also where Manifesta 11 reveals its shortcomings. The exhibition in the more traditional white cube venues is weighed down by too many “historical” works, which gives the impression that the curator was not confident enough that the 30 joint ventures could stand alone and aptly convey his concept.

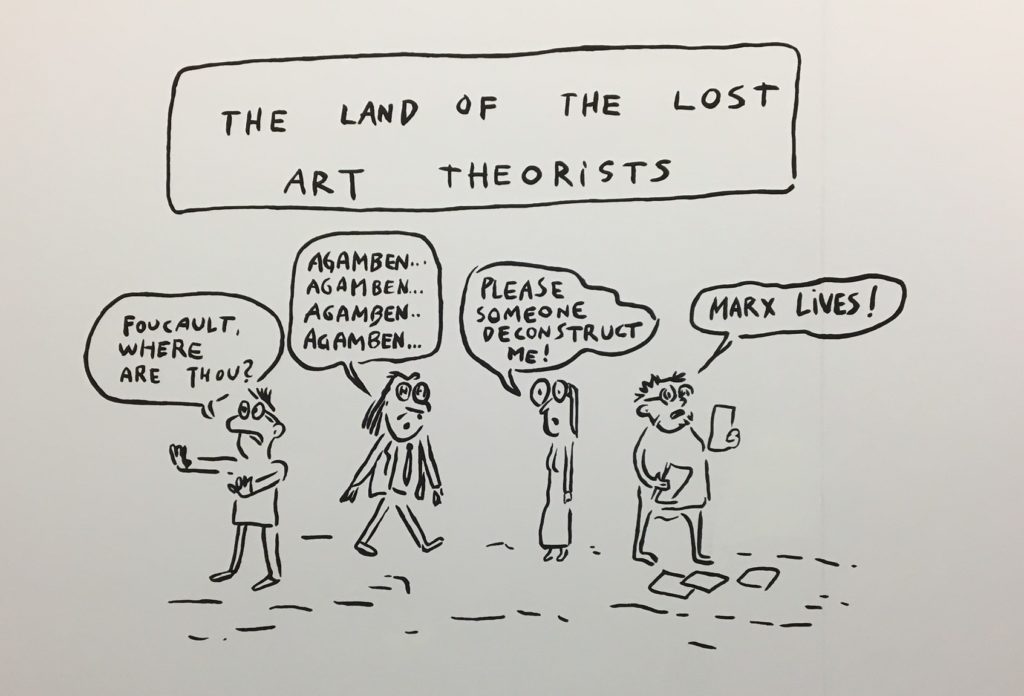

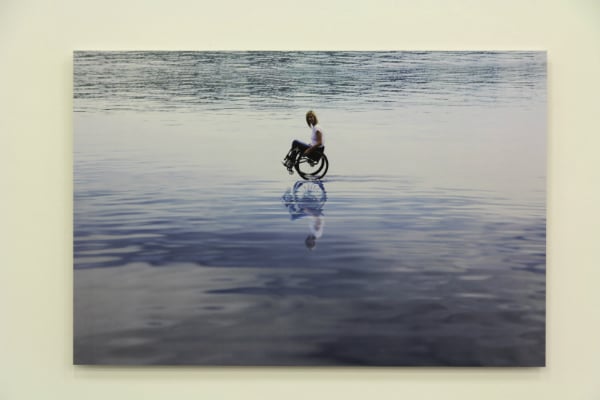

Pablo Helguera’s “Artoons” for Manifesta 11. Photo: Courtesy of artnet News

What emerges from the biennial as a parallel theme is a questioning of the work of the artist, that amounts to navel-gazing. There is, however, a collaboration that approaches this very tendency, and is an absolute highlight of the show. Pablo Helguera created a cartoon series published in the Sunday supplement of Das Magazin. His main character, Bolito Husserl, is an overqualified unemployed male looking for a job. His ventures into the art world, presented in a series of Artoons, are hilarious, on point, and should come out as a series in and of itself.

Manifesta 11 takes place in Zurich from June 11 – September 18.