In 2006, Pier Luigi Cecioni traveled from Florence to the People’s Republic of North Korea as a visiting musician. After his hosts showed him some North Korean art, he left with an entirely new mission: He planned to become an art dealer.

For more than a decade since then, Cecioni has served as an international gallerist for North Korea’s artists. He imports posters, embroidery, and paintings from the North Korean capital of Pyongyang to his small gallery in a town outside of Tuscany, in Italy. In the wake of Kim Jong-un’s historic summit with US President Donald Trump, global interest in North Korea has never been higher, he says.

This interest hasn’t had a major effect on his business, however—because technically, he is unable to sell new work being made in North Korea. Last year, Cecioni had to effectively shutter his import business after the United Nations slapped new sanctions on the country.

UN officials claimed that the monumental sculptures being produced by North Korean artists—such as the 164-foot-tall African Resistance Monument in Senegal or the Grand Panorama Museum in Cambodia—were enabling the country to evade existing sanctions. Several former North Korean state artists have also spoken out about the abuse they experienced at the hands of the government. Although Cecioni claims the proceeds from his dealings go directly to the artists and not to the North Korean regime, his business has been under heightened scrutiny since then.

And indeed, the monumental works, as well as the kinds of small watercolors and moody landscapes sold by Cecioni, all come from the same place: Mansudae Studios, one of the largest art studios in the world, which counts as many as 4,000 employees. The set-up is a little unusual, but if you are a creative type in North Korea, an invitation to work at Mansudae is the ultimate career move.

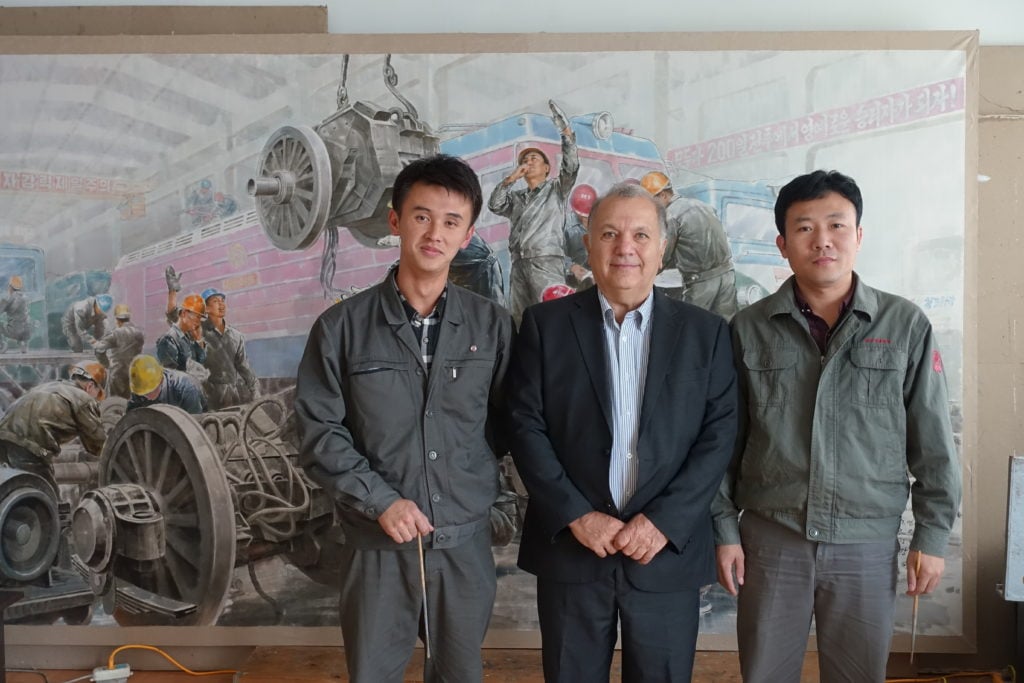

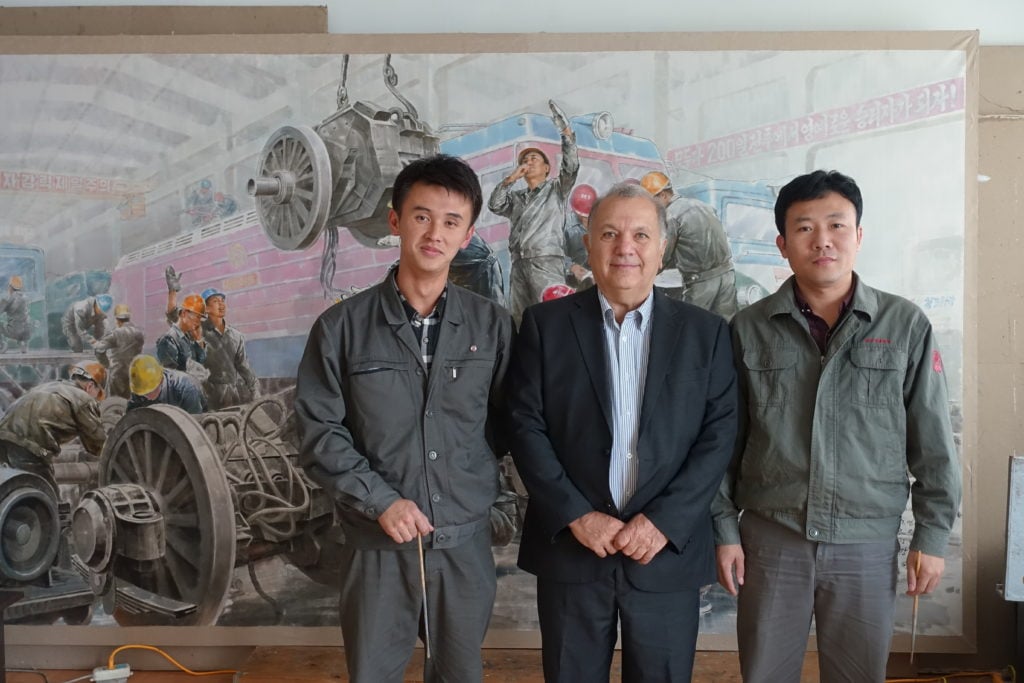

Cecioni says his unlikely role as the gateway for North Korean art to the West developed out of pure interest: He simply thought it was of excellent quality. When he offered to arrange international exhibitions and sell some of the works in Italy, the country agreed to let him—and what started out as a lark became a career. Works now cost up to €9,000 ($10,450) and, before sanctions set in, they could be shipped from Pyongyang to his gallery via DHL in just five days. Last summer, however, all of this came to halt.

Cecioni describes a rapidly evolving Pyongyang—with more shops, cell phones, and cars (even small traffic jams). All of this is very different, he says, from when he started dealing North Korean art a decade ago. While relations with the West continue to swing between hot and cold, Cecioni, a firm believer in the healing power of art, patiently waits for the sanctions to end. He spoke to us from Italy about how his business developed—and what he plans to do next.

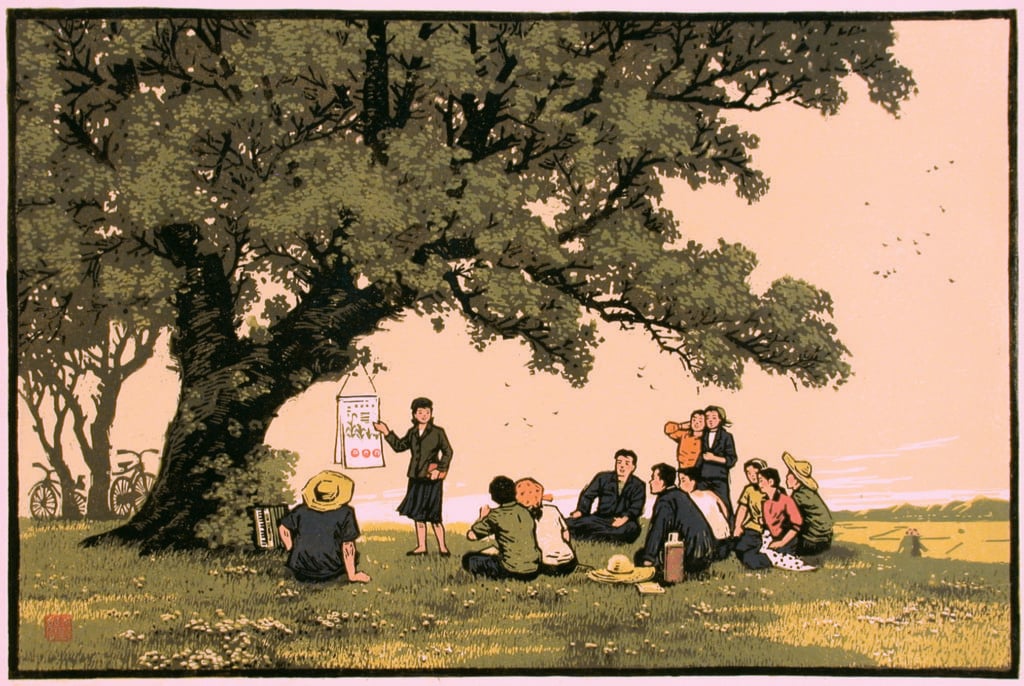

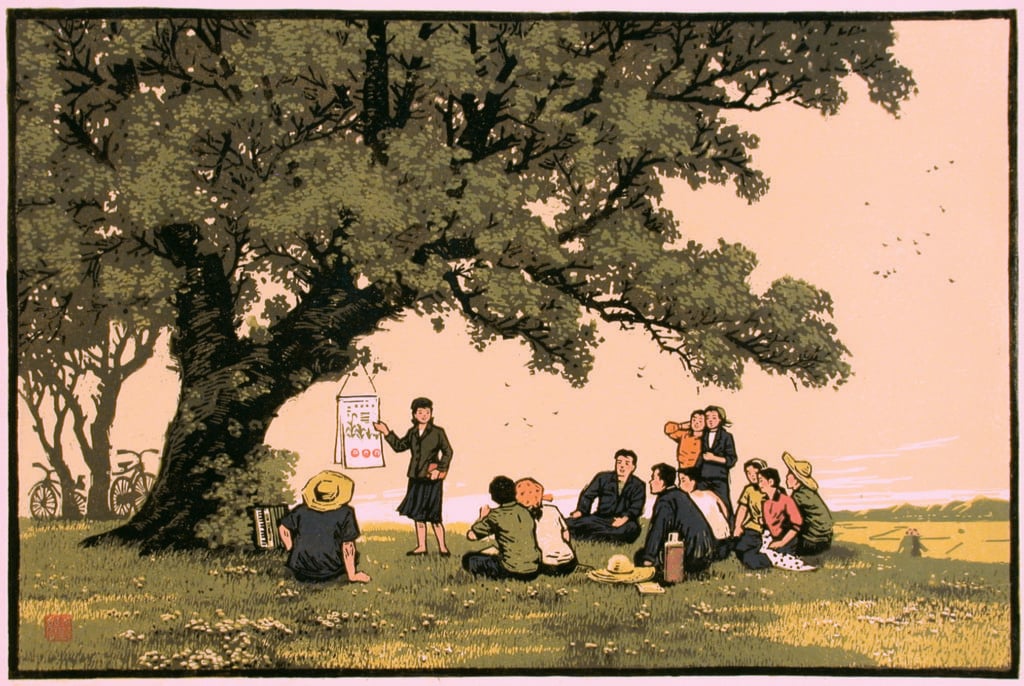

Woodcut by Kim Bong Ju, a female Merited Artist. Photo courtesy North Korean Art Gallery.

What is the North Korean art scene like?

The art scene in North Korea is rather straightforward, and I think one aspect that is really unique is that all the best artists work within Mansudae Studios. It’s massive: about 4,000 people and about 800 artists in over 120,000 square meters. It’s like an American campus, but it’s not a school. All the artists already have university degrees and their ages vary from early 20s to 70s. Artists go there to work, but they live in Pyongyang; it’s not a residency.

Currently, you have some 300 works in your collection. What types of pieces do you have?

I have mostly oil paintings and “Korean paintings,” which are ink on paper works—the latter is the most traditional technique. Oil painting in Korea only appeared in the 1960s, so it’s a relatively new technique. I also collect woodcuts, drawings, embroideries, and watercolors, which are quite popular.

Art dealer Pier Luigi Cecioni with Mansudae artists Pak Ouk Chol (R) and Kang Un Hyok in front of a work in progress. Courtesy North Korean Art Gallery.

Operating this gallery is not simply a business decision. What are your intentions with it beyond that?

There are so many misconceptions about North Korea. I don’t want to defend the regime, but there are many representations of the country that are biased and false. I’ve had the rare opportunity to see it from a different perspective. Most people who visit are tourists, diplomats, or [part of] an NGO, and so their relationship is not so free. If I want to walk around Pyongyang, I can do it.

What do you think Mansudae’s intention was in going into business with you?

They were interested in being presented to the West. They had never been exhibited in the West when I started. But simply, they wanted to sell their work and become better known—as all artists do.

There are currently sanctions imposed on Mansudae Studios. Because of that, as a dealer, your business is on hold right now. Can you explain that to me?

I cannot buy art from North Korea, but we can sell what we have imported before the UN sanctions went into effect. I’m currently withholding works, especially handmade posters, because I would prefer to wait and see what happens.

The UN essentially sanctioned Mansudae Studios from exporting larger statues, but these works are completely different from the other types of art that are made there. The larger [political] statues, which have been produced since the ’70s, are a separate business.

The art I am speaking about is more conventional, with much smaller implications for the economy. When I tell people that this art has been sanctioned, many are surprised and, in fact, I think it’s a mistake. The money from the art we deal goes back to the studio and to its artists to pay for materials [not to the North Korean regime].

Farewell Father General, a handpainted poster from Mansudae Art Studio. Courtesy North Korean Gallery.

Are you actively lobbying against these sanctions?

The UN approached me. After the sanctions on Mansudae Studios, they tried to find out about my role. I’m also in touch with the Italian Foreign Ministry and the Italian police that look after international trade. I’m trying a bit through my connections to offer a different view.

I really think it is counterproductive to put sanctions on art. When people come to my exhibitions of North Korean art, they begin to think a little more about North Korea and to see it less through [the lens of] stereotypes and bias. I do not want to support the regime, but I believe that partly, the risk of war is based on misconceptions.

The recent Olympics brought about a dialogue between the two Koreas. I really think that art, like sports, can be an instrument of reciprocal understanding, and ultimately, perhaps, of peace.

Because the works cannot be acquired easily and are not being sold, are they going up in value?

Possibly, but it is difficult to say because I am essentially the largest market in the West, so we set the prices. Now, we’re not really doing much activity, but by choice. Requests have increased and attention on North Korea has increased interest in all aspects of the country—including art. North Korea is in the news right now, and it’s in the mind of the public.

Inside the Mansudae Art Studio complex in Pyongyang, North Korean People’s Republic. Photo by Pier Luigi Cecioni.

You mostly sell these so-called posters, but they’re not posters in the traditional, mass-produced sense. These are usually hand-painted.

These works come out of a long tradition of poster-making. Each year, [artists at Mansudae] make about 50 new posters with themes based on goals given out at the beginning of the year by the state. Some can be political, but they can be [about] anything, really. They might say, “Let’s promote something like, ‘If Americans come and invade us, we will stop them with one blow!’” A proof is then made, and if the proof is approved, then this poster is reproduced, either printed or painted, by several artists.

How does production work at Mansudae?

They are assigned projects sometimes, but if one wants to make a landscape or paint a mountain, one simply makes it. And abstract art is not forbidden—they’re just not interested in it. Conceptual art is also not considered art. They don’t care about it.

I read that Mansudae Studio’s artists came to visit Italy on a few occassions.

They came more than a couple times. Frankly, I thought they would be more impressed by our abundance and our wealth. They noticed, but they didn’t seem to want to stay here. It’s the same as when I meet with North Korean diplomats—when they go back, they are not sad.

Country Dance by People’s Artist and vice president of the Mansudae Art Studio, Kim Song Min. Courtesy North Korean Art Gallery.

When you took them around the city, to Italian galleries or museums, what did they think of contemporary art?

Once, I took around 12 of the most important artists in the country around Florence and Rome. I took them to the Uffizi, the Vatican Museums, and to an exhibition of contemporary conceptual art. They found [the conceptual art show] funny—not in an obnoxious way, they just found it kind of comical. But they knew the Western masters, like Michelangelo, Leonardo, and Botticelli. They had studied those in university.

It was interesting: As an Italian, I know who the masters are, and I am aware of who is a minor or a major artist. But they had fresh eyes in a way, so they may have liked a work that to my eyes was by a minor artist. There are some monuments in Florence that are almost insignificant to us, but they found them interesting. They were more interested in the figuration than in any of the religious symbolism.

A painting of Mount Paektu from Mansudae Art Studio, depicting a sacred mountain especially for North Koreans but also for South Koreans. Photo courtesy North Korean Art Gallery.

Does fame work differently for the art world there?

Fame is not like [it is] here. Although some artists are definitely more famous than others, they are not household names. In Mansudae Studios, however, there is definitely a hierarchy. There are two designations given to artists: People’s Artists, the highest title, or Merited Artists. But in general, you have made it as an artist when you are invited to work at Mansudae.

There also isn’t the same kind of hierarchy [as in the Western art world]. The artists who practice different techniques are considered just as good as [any other]. Merited or People’s Artists be embroiderers; they are as valued as sculptors.

Do you have plans to go back to North Korea?

I planned to go back last year to work on an exhibition of posters that was to be held in Italy in September. I had invited four artists to come here as well—but none of that happened because I had to cancel the show. I couldn’t get the works here because of the sanctions. It was a disappointment for us all, but especially for the artists who were supposed to come. I think it would have been extremely interesting, especially in this current period, to have such an exhibition.