Art & Exhibitions

Peter Marino Curates A Sensual Robert Mapplethorpe Exhibition in Paris

Marino has been collecting Mapplethorpe since the mid 80s.

Photo Manolo Yilera

Marino has been collecting Mapplethorpe since the mid 80s.

Emily Nathan

Sipping tea at Paris’s Hotel Bristol last week—clad in his signature uniform of head-to-toe black leather—architect and designer Peter Marino wanted to set the record straight. “Listen, Mapplethorpe did portraits like I do boutique stores: to earn a living. Nobody was paying him for shots of“—he raised his eyebrows, and looked down at his lap—“or of flowers or nude men. So you have to assume that he did those because he loved it, because he was obsessed with it, because that was obviously in his soul. I always say you take an artist’s strongest obsession and that’s their best work.”

Such is the scope of XYZ, a Marino-curated exhibition of images mainly from the archives at of The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation based in New York, titled after the renowned photographer’s iconic series of portfolios from 1978—81. Opened on January 28 at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac and on view through March 5, the show is the latest in a series of presentations in which the gallery keeps the Mapplethorpe Estate fresh by inviting a guest curator to re-envision it, guided by his or her own subjective inclinations.

Robert Mapplethorpe Bird Of Paradise (1981)

Photo: courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac

Following previous installations by Hedi Slimane, Robert Wilson, Sofia Coppola, and Isabelle Huppert, the New York-based Marino has dedicated each of three walls to one of the themes he found most prominent in Mapplethorpe’s X,Y, and Z portfolios: X for sex—explicit scenes starring men tied up in harnesses and chains—Y for flowers, and Z for nudes. In true Marino style, his design is distinctly architectural, and his chosen images occupy the space with a clean, symmetrical visual logic.

“I look back at X,Y, and Z and it was really a highpoint; we have definitely regressed since then,” he said, noting that even the rawest of Mapplethorpe photographs—which he has been collecting since the mid 80s—is tempered by original experimentation in technique and composition. “In the context of the 70s, I remember thinking he was just pushing the envelope a little. It wasn’t so shocking then.”

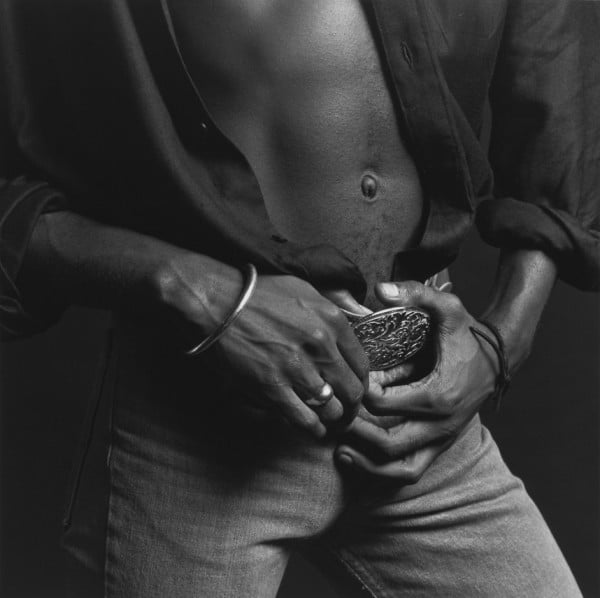

Robert Mapplethorpe

Phillip Prioleau (1980)

Photo: Courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropc

Although Marino’s curatorial goal was certainly not to shock, he explained that recent Mapplethorpe shows at the Musée Rodin and the Grand Palais missed the mark, focusing on images everybody knows too well. His presentation, therefore, begins with a room of Polaroids from the 1970s that set up the artist’s concerns—candid shots of the New York sex scene, yes, but also bold experimentations with form and abstraction.

They are small, and the devil is in the details; viewers are rewarded for taking a moment to look at them up close. There are crisp tangles of leather whips and holsters on the white canvas of a bed sheet, evoking Dutch still lifes; a series of photographic nods to the Surrealists recall Dali and Meret Oppenheim: a spoon, a black pile of ground coffee, and the round sphere of a white plate play against a checkered gingham tablecloth in varying arrangements. “Mapplethorpe was engaging the great movements of art at that point, let’s call it Nouveau Realism, or real subjects but done in a kind of outlandish way,” Marino noted.

Robert Mapplethorpe, Jason, (1983)

Photo: courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac, © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved.

Inside the main gallery, the X wall offers viewers the chance to see images that were not included in Mapplethorpe’s selection, including a shot or two that is slightly blurry. “He obviously did it on purpose, he was playing with it, and the fuzziness gives it a more emotional context,” Marino said. “He took for his books always the clearest one, but I want to show that this was part of his process.”

The Y wall, meanwhile, represents what Marino describes as the highest point of Mapplethorpe’s “intellectual dilemmas”: Flowers that evoke primordial blooms, Minimalist abstractions, and genitalia, all at once, placed in tense juxtapositions with positive and negative space; abstractions of shape and light. “I picked flowers that hopefully you have never seen before,” he said. “These are startling images, and they make you play this intellectual game of flower/sex/flower/sex. There is one photo of a tulip balancing on the point of a knife—and there is so much tension and sensuality in this image, I swear it’s as good as Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel.”

Robert Mapplethorpe, Orchid and Hand (1983)

Photo: courtesy Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac

On the third wall, Marino has explored the photographer’s fascination with the bodies of naked men. Presented like landscapes, expanses of their limbs and the mounds of their muscles morph into slopes, peaks and valleys.

“If Mapplethorpe were really only snapping body parts, none of us would be looking at him today,” Marino concluded. “But that’s the modernity of it: he was playing with compositions and then mixing it with explicit sex. This is what a great artist does, defying his times. It was about sexual liberation, but explored with great poetry. Ultimately, it’s a paean to beauty.”

“XYZ Curated by Peter Marino” is on view at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac from January 28 – March 5, 2016