Everyone has their own way of keeping track of time during lockdown.

Like many artists who have been throwing themselves into their work, UK artist Marc Quinn is no exception. Since the lockdown began in mid-March, the YBA artist best known for putting pints of his blood into a sculpted bust of his own head has been creating a striking visual diary of the unfolding public health situation through a series of paintings. Every day, from isolation in his London studio, the artist has been scouring the web for news, and creating semi-abstract paintings from larger-than-life prints of the articles that speak to him.

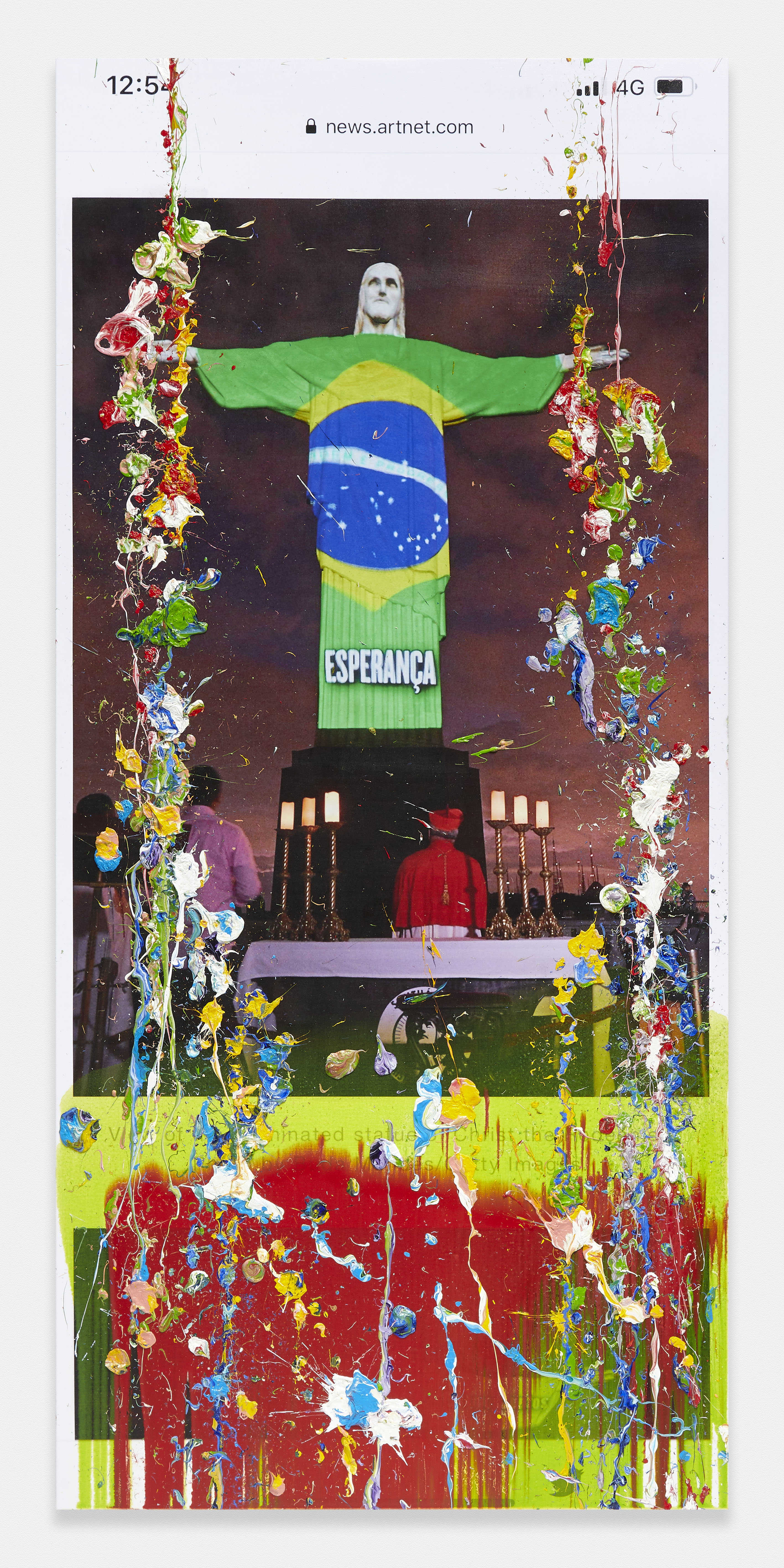

These so-called “Viral Paintings” are the newest phase of the artist’s ongoing “History Paintings” which began in 2009 and looked at how current events are communicated through the media—offering an in-real-time look at history in the making. While earlier examples have consisted of paint strewn over hyperreal paintings of press photography, this newest iteration is painted on top of blown-up screenshots of news articles the artist takes on his phone to reflect the accelerated pace of the online news cycle.

“What’s important to me is engaging with one of the most significant stories of our time, in real time,” Quinn tells Artnet News. “To me there is a very strong element of performance and ritual in the creation of these works.” After spending several hours reading morning news stories, he prints out a couple of articles and then spends the next two or three hours painting. He has completed around 20 paintings. “Afterwards I’m completely exhausted,” he says.

Pages from a variety of media sites including the New York Times and Artnet News feature in the series. “I choose the articles depending on my reaction to the news on any given day,” Quinn says. Particularly important to his choices are the photographs included alongside these stories, such as the powerful message of hope that was projected onto Rio’s Christ the Redeemer statue this April.

Marc Quinn, Viral Painting. Baby Erin Bates, (Painted 15 April 2020) (2020). Courtesy and copyright Marc Quinn studio.

The artist explains that he was inspired by a longstanding tradition of art-making during periods of crisis, including Goya’s “The Disasters of War” series that was created during the Peninsular War in the early 1800s. Quinn says the work is also a nod to Picasso’s paintings that came out of Paris during World War II, as well as works made by the German-Jewish artist Charlotte Salomon during the Nazis rise to power in Germany and their subsequent occupation of France.

“These eye-witness series feel so much more important to me than what was created in recollection years later,” Quinn says. “I feel it’s an artist’s job to bear witness to the time that we live in.”

While Quinn has been busy creating his own artistic record, the artist feels there has been a “missed opportunity” from the government to encourage other artists to track the crisis, through historic programs like the “official war artist” initiative that engaged artists to create a visual record of the country throughout periods of war in previous centuries. “Brilliant artworks were made by hundreds of artists, these works now serve as an incredible archive of that period,” he says. “I’d love to see the government doing something like that now.”

Quinn plans to eventually sell the series and donate 10 percent of the proceeds to the UK’s National Health Service and the WHO. Before that, however, he hopes to see them shown in a museum. “Ideally, given that they are documenting this period of shared experience, I’d love for them to be seen by the public,” he says.